Investor Euphoria And The Anatomy Of A Market Crash

Submitted by Brent Johnson, courtesy of MacroAlchemist.com

Investor Euphoria & The Anatomy of a Market Crash

Executive Summary

Markets move in cycles of innovation and speculation, and the present surge in artificial intelligence is no exception.

Today’s AI boom displays nearly all the features that have defined past bubbles—soaring valuations, concentrated flows of capital, euphoric investor sentiment, and media narratives that reinforce expectations of unstoppable growth. By most measures, the parallels extend beyond resemblance: the speculative fervor around AI rivals and in many ways exceeds the South Sea Bubble, the 1840s railway mania, the 1920s boom, the dot-com era, and the subprime mortgage frenzy.

At the center of the storm lies a combustible mix of genuine technological promise, abundant liquidity, and human psychology. Investors see the potential for world-changing transformation, credit remains accessible enough to fuel risk-taking, and fear of missing out drives behavior to extremes.

The result is an environment where both startups and established firms are valued as though flawless execution, relentless hypergrowth, and immediate mass adoption were inevitable.

Such assumptions are unsustainable.

Every historical bubble has revealed the danger of expectations drifting too far from reality. In the late 1990s, the mantra was that profits no longer mattered; today, many AI firms are projecting revenues and margins based on unproven scenarios.

When the gap between projections and actual results grows wide, the risks compound. Financial losses are the most visible outcome, but history shows that misconduct often follows. From the railway booms of the 19th century to Enron, WorldCom, and the more recent mortgage excesses, periods of extreme optimism have created fertile ground for creative accounting, misrepresentation, and fraud.

The warning signs are well known.

Extreme valuations relative to tangible earnings, heavy concentration of capital in a handful of celebrated winners, and the easy availability of venture funding or leverage all raise systemic risk. The proliferation of complex financial products magnifies fragility, turning small disruptions into cascading stress events.

And as always, the insistence that “this time is different” echoes loudly in the background, emboldening herd behavior while discouraging sober analysis.

When both retail and institutional investors chase momentum trades rather than fundamentals, the system edges closer to its breaking point.

History also offers a guide to navigating these environments.

Investors who wish to participate in innovation without being consumed by its excesses must apply a disciplined, historically informed framework. This means challenging assumptions behind valuations, scrutinizing profit projections, monitoring leverage and liquidity conditions, and examining whether business models are robust enough to withstand shocks.

It also means cultivating behavioral awareness—recognizing that FOMO, herd instincts, and narrative intoxication can overwhelm even the most seasoned decision-makers.

Perhaps most critically, vigilance against aggressive accounting or unrealistic guidance is essential, since the incentives for embellishment grow strongest in speculative peaks.

This study is not written from a position of permanent pessimism. It is a general exploration of the anatomy of market crashes, designed to provide a framework for understanding why speculative cycles form and how they unwind.

At the same time, it is timely. The conditions we observe today suggest that a sharp correction is not a distant possibility but a near-term risk.

And our goal is not to preach fear.

Rather, it is to help prepare readers for the rogue waves that history tells us appear just when the waters seem calmest. We believe extraordinary opportunities will emerge once excesses are flushed from the system, but to capture them, investors must first survive the volatility that lies ahead.

The sections that follow build upon this foundation, beginning with the AI boom itself. As the most vivid present-day example of innovation colliding with speculation, it provides a live case study of how opportunity and risk entwine, setting the stage for both painful collapse and enduring renewal.

BackgroundFinancial markets have always swung between fear & greed, moments of stability & episodes of mania.

Crashes are rarely a product of truly unforeseen shocks; more often, they are the inevitable outcome of long stretches of investor euphoria. These euphoric phases are characterized by an intoxicating mix of extreme optimism, soaring valuations, the easy availability of credit, and the conviction that some new technological or economic paradigm justifies abandoning the lessons of history.

In hindsight, signals of excess usually appear glaring. But in the moment, investors, institutions, and even regulators are lulled by persuasive narratives and the apparent reliability of ever-rising prices.

This paper examines the anatomy of such euphoric cycles. It explores the conditions that allow optimism to grow unchecked, the signals that can be seen in real time, the distortions that only reveal themselves after collapse, and the enduring lessons investors can carry forward.

Historical examples ranging from tulip mania to the dot-com boom to the SPAC frenzy of 2021, paired with data on valuations, leverage, IPOs, and liquidity, provide the lens through which we analyze how manias build, why they unravel, and how disciplined investors can prepare for their aftermath.

Conditions That Breed Euphoria

Euphoria tends to be powered by three main elements:

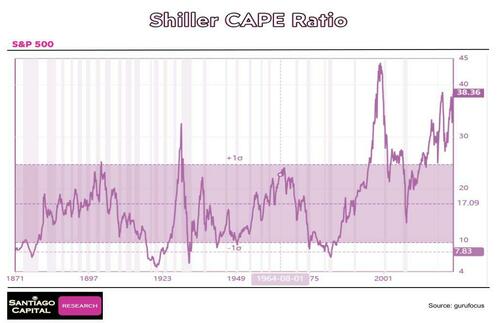

Valuation is the most immediate signal. Robert Shiller’s CAPE ratio offers a century-long view of how earnings multiples expand during speculative eras.

In 1929, CAPE rose above 32 before collapsing to 5 in the depths of the Depression. In 2000, at the height of the dot-com bubble, it touched 44—a record that stood until today’s era, when CAPE once again surged into the high-30s.

Each peak was followed by years, even decades, of muted returns.

Elevated valuations may not trigger an instant collapse, but they reliably compress long-run forward returns, leaving markets vulnerable to sudden shifts in sentiment.

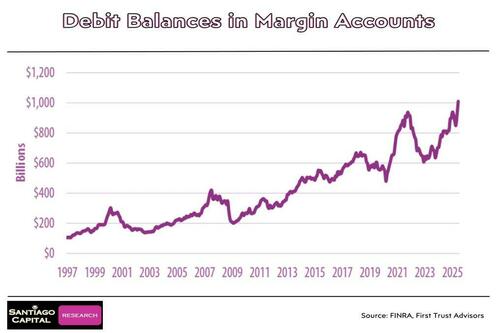

Credit availability provides the second engine.

Liquidity supplied by banks, shadow lenders, or central banks amplifies speculation. Margin debt offers a stark illustration: it reached $278 billion in March 2000, $381 billion in July 2007, and $935 billion in October 2021, before topping $1 trillion in the current cycle. Each surge coincided with a wave of risk-taking; each retracement magnified losses as forced selling cascaded through the system.

The third element is narrative.

Bubbles are rarely built on nothing; they are anchored in genuine shifts. Railroads in the nineteenth century, electrification and automobiles in the early twentieth, the internet in the 1990s, and AI and cryptocurrencies in the 2020s all provided credible visions of boundless growth. Yet markets consistently priced these innovations with unrealistic speed and scale.

The phrase “this time is different” echoes across every euphoric episode, deployed to rationalize valuations and leverage levels that in calmer times would be dismissed as reckless.

Signals Visible in Real Time

Even at the height of mania, warning signs are visible to those willing to look.

Retail investor surges are a common marker. The 1920s saw households speculating in bucket shops with leveraged stock bets. The 1990s featured day traders armed with online brokerages and chat-room tips. In the 2020s, commission-free apps fueled meme-stock frenzies as millions piled into GameStop, AMC, and other speculative trades.

When investing turns into cultural entertainment, markets are already deep in the euphoric phase.

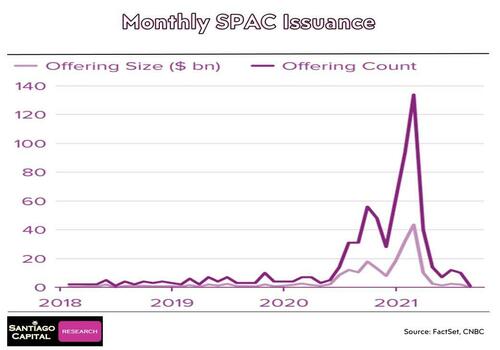

Issuance is another signal.

Nearly 500 IPOs flooded markets in 1999, many from unprofitable firms. In 2021, more than 1,000 listings, dominated by SPACs, eclipsed even that surge. Such waves demonstrate not only investor appetite but also opportunism by issuers exploiting inflated valuations.

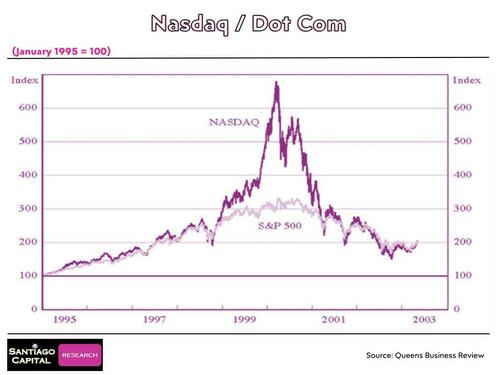

Price patterns often provide confirmation. Parabolic moves—where prices accelerate beyond sustainability—are the classic tell. The NASDAQ between 1998 and 2000, Bitcoin in 2017 and 2021, and certain AI stocks in 2023–2025 all displayed this behavior. Media coverage follows suit, shifting to unrelenting positivity, with stories of overnight millionaires and celebrity endorsements reinforcing the frenzy.

Speculative mania reaches full bloom once it enters the mainstream cultural consciousness.

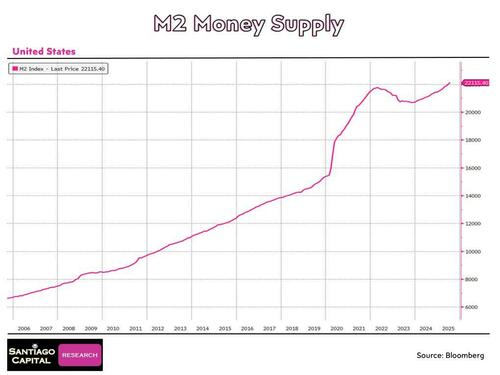

Liquidity measures add further evidence.

In 2020, U.S. M2 money supply expanded nearly 25% year-on-year—the fastest pace since World War II—fueled by stimulus checks, ultra-low rates, and massive asset purchases. That surge powered booms in equities, crypto, and collectibles. When M2 contracted in 2022, risk assets fell sharply, revealing how dependent euphoria is on the tide of liquidity.

Signals Clearer Only in Hindsight

Other distortions only emerge after collapse.

Cheap capital enables malinvestment: dot-com firms burning through cash on marketing in the late 1990s, SPAC startups of 2020–2021 collapsing once easy funding evaporated. Hidden leverage is another revelation. In 2008, mortgage-backed securities and CDOs concealed systemic exposures; in 2022, crypto lenders failed for similar reasons.

Narratives, too, undergo a dramatic pivot.

During booms, the focus is boundless growth. After crashes, scrutiny shifts to governance, unit economics, and sustainability. The shift from “how big can this get?” to “can this survive?” is the hallmark of reversal.

Accounting misrepresentation is another thread.

Enron remains the archetype: vendor financing, premature revenue recognition, and other tricks prolonged the illusion, until collapse became unavoidable. When Enron fell, it dragged down Arthur Andersen, one of the world’s most prestigious accounting firms, underscoring how far the damage can spread.

Behavioral Dynamics

Beneath these financial patterns lie recurring psychological forces.

Herding compels investors to follow the crowd, reinforcing momentum. Overconfidence convinces traders they will exit before the downturn, even as exposure builds. Narrative bias gives stories of transformation primacy over sober analysis. Risk perception erodes as practices once considered reckless become normalized.

This cycle of behavior repeats with uncanny consistency.

Case Studies in EuphoriaSpeculative manias arise when optimism, innovation, and sudden wealth converge to fire the collective imagination — and when easy credit provides the means for everyone to participate.

Each instance has its own cultural markers: tulips in 17th-century Holland, the South Sea schemes in Enlightenment England, radio and automobiles in 1920s America, internet startups at the turn of the millennium, securitized mortgages in the 2000s, and meme stocks during the pandemic era.

Beneath these surface differences lies a common emotional cycle: excitement, enthusiasm, greed, and, eventually, panic.

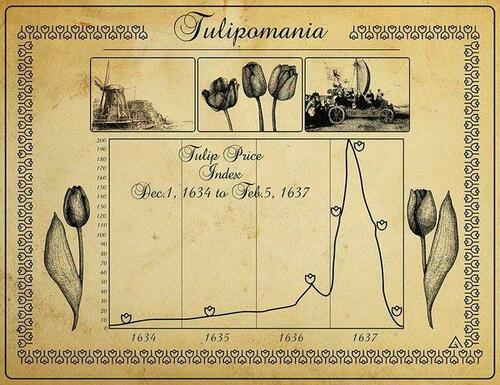

Tulip Mania (1637)

The Tulip Mania of 1637 is often remembered as the first great financial bubble.

It was never simply about a flower. In the Dutch Golden Age, Amsterdam had become the center of world trade, and merchants, craftsmen, and artisans were enriched by global commerce. Tulips, newly imported from the Ottoman Empire, were prized as luxury goods, their vivid colors and striking patterns caused by mosaic viruses.

To own rare bulbs was to signal both taste and social standing.

Demand soon transformed tulips from status symbols into speculative assets. What made the episode remarkable was how deeply it penetrated Dutch society. Farmers, artisans, and small merchants speculated, often through futures contracts that allowed wagers on bulbs never actually exchanged.

At the peak, a single bulb could trade for more than ten times the annual wage of a skilled worker, with anecdotes of prices rivaling canal-side mansions.

When an ordinary auction failed to draw expected bids, confidence evaporated almost instantly. Prices collapsed, contracts went worthless, and while the Dutch economy absorbed the shock, the episode left an enduring lesson: when prestige and speculation merge, markets can detach from reality.

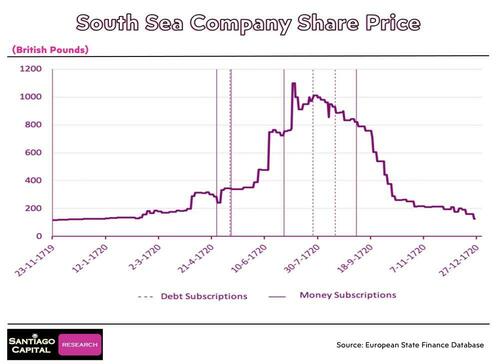

South Sea Bubble (1720)

The South Sea Bubble of 1720 followed a similar trajectory but with greater institutional weight.

Early-eighteenth-century England was encumbered with war debts, and the South Sea Company proposed an elegant solution: it would assume the national debt in exchange for shares and monopoly rights to trade with Spanish South America. Promoted by politicians and endorsed as virtually risk-free, the scheme sent shares soaring.

Investors ranged from the aristocracy to common citizens, with even the royal family participating. The age of Enlightenment optimism encouraged faith in boundless opportunities, and opportunists launched dozens of copycat ventures — some laughably vague, such as “a company for carrying out an undertaking of great advantage, but nobody to know what it is.”

When it became clear that South Sea’s trading prospects were illusory and its debt-conversion model untenable, the bubble collapsed.

Families lost fortunes, public fury mounted, and Parliament was forced to investigate.

The lesson was broader than speculation: it underscored the dangerous interplay between state endorsement, finance, and public trust, a formative moment in British financial history.

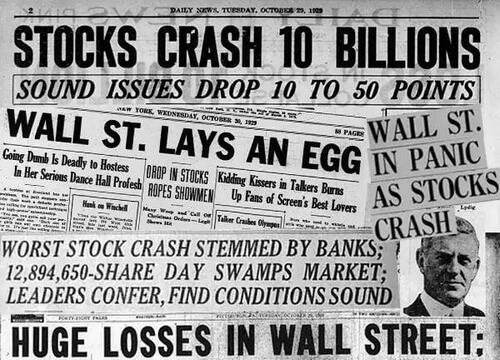

1929 Crash

The Wall Street Crash of 1929 captured the euphoric mix of technological innovation, cultural exuberance, and financial leverage.

The 1920s were transformative: automobiles expanded mobility, radios connected homes, and electric appliances revolutionized daily life. Jazz, cinema, and the cultural energy of the decade reinforced the sense that a new era of prosperity was permanent. Corporate profits rose, stock ownership broadened, and margin loans enabled investors to buy shares with borrowed funds.

Newspapers and radio personalities celebrated the market as a one-way ticket to riches.

By 1929, valuations were stretched to extremes, but the cultural conviction in progress drowned out skepticism. When the downturn came, margin calls cascaded into panic selling. The crash marked the abrupt end of the Roaring Twenties, shattering faith in markets and ushering in the hardship of the Great Depression.

Dot-com Bubble (1999–2000)

The dot-com bubble of the late 1990s and early 2000s provides one of the clearest modern parallels.

The internet represented a genuine technological revolution, but as in earlier eras, it was mythologized as the foundation of a “new economy” where old valuation rules no longer applied. Startups became cultural icons, showered with venture capital and ushered to market through a flood of IPOs.

Retail investors, empowered by online brokerages, joined the rush. Cultural artifacts of the time included Super Bowl ads from unprofitable firms and magazine covers proclaiming the death of brick-and-mortar business. Analysts argued that “eyeballs” and “clicks” mattered more than profits.

The Shiller CAPE ratio surged to 44, a historic extreme. When the bubble burst, the NASDAQ lost nearly 80% of its value over two years, erasing fortunes and careers. Yet, as in 1929, the underlying innovations endured: Amazon, Google, and eBay eventually thrived, just as autos and radios had before them.

The lesson was not that innovation lacked value but that speculation accelerates expectations far beyond what reality can deliver.

Global Financial Crisis (2008)

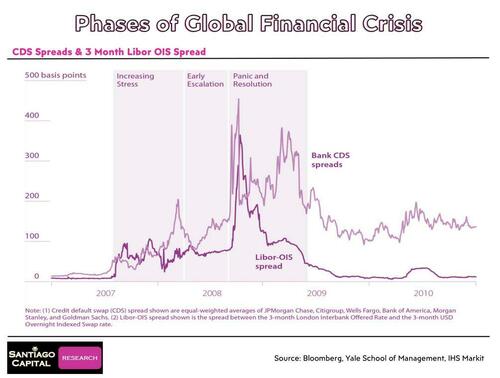

The Global Financial Crisis of 2008 extended the pattern of euphoria into credit markets.

Unlike the dot-com boom, this was not a mania of households buying internet stocks but of institutions building towers of leverage on the foundation of housing. The cultural backdrop was belief in homeownership as the cornerstone of the American dream, coupled with faith that housing prices never declined nationwide.

Banks extended credit to increasingly unqualified borrowers.

Wall Street packaged mortgages into securities and collateralized debt obligations, which rating agencies blessed with investment-grade status. Yield-hungry institutional investors bought them eagerly.

When home prices began to slip in 2006 and 2007, the illusion collapsed.

Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers, and other giants fell, credit markets froze, and the crisis cascaded into the worst global recession since the 1930s. The central narrative of stability and safety gave way to systemic fragility and mistrust.

SPAC and Meme-Stock Boom (2020–2021)

The SPAC and meme-stock boom of 2020–2021 showed how quickly euphoria adapts to new environments.

The COVID-19 pandemic initially sparked panic, but unprecedented monetary and fiscal stimulus soon reversed the collapse. With near-zero rates, trillions in government transfers, and record household savings, retail investors found themselves with capital to deploy.

Platforms such as Robinhood made trading free and gamified, while online communities on Reddit and Twitter forged a culture of collective speculation. Meme stocks like GameStop and AMC became cultural symbols, celebrated less for fundamentals than as vehicles of rebellion against Wall Street. At the same time, SPACs multiplied, providing fast-track listings for untested firms.

In 2021 alone, more than 600 SPACs raised capital, reflecting both investor enthusiasm and a cultural belief in disruption. By 2022, tightening monetary policy and inflation punctured the boom.

Meme stocks, SPACs, and even cryptocurrencies collapsed, leaving behind another lesson: liquidity, psychology, and culture can generate illusions of permanence that dissolve almost overnight.

Taken together, these various episodes show how societies repeatedly convince themselves they stand on the edge of transformation — whether through flowers, global trade, industry, technology, or digital platforms.

Credit expansion, cultural narrative, and mass participation provide the fuel.

Collapse brings destruction, reform, and reflection, but also resilience.

In nearly every case, the innovation at the core of the bubble — tulips aside — survived the washout.

What is left behind is both a cautionary tale and a foundation for the future.

* * *

Continue reading at the Macro Alchemist or the pdf below.

Loading recommendations...