Publish or perish: The billion dollar debate over research funding at public universities

(The Center Square) – When it comes to higher education, taxpayers, legislators and educators on both sides of the aisle seem to agree that something is broken and the cost is too high.

That’s about where the agreement ends.

Enter artificial intelligence. In the wake of federal threats to freeze funds and halt research at many of the nation’s most prestigious institutions, The Center Square was given the opportunity to look at federal grants on a broad scale.

More CoverageThis is the first in a series of stories examining research funding of higher education institutions, with a particular focus on Pennsylvania's most prestigious universities.

Jennica Pounds, widely known by her X handle, @DataRepublican, is a DOGE-style investigator who uses AI technology to mine the inner workings of the U.S. government. Within that scope falls huge Biden-era spending bills like the $280 billion CHIPS and Science Act and the more than $700 billion Inflation Reduction Act.

To better understand how the money was used, Pounds trained her sights on Pennsylvania’s most recognizable public institutions: Penn State University and the University of Pittsburgh. The data also encompassed the University of Pennsylvania, President Donald Trump’s own Ivy League alma mater.

The entire Ivy League has drawn criticism from the Trump administration, citing massive endowments, exorbitant tuition prices, “woke” policies, and alleged tolerance of antisemitism. The way UPenn’s budget factors in federal grant dollars, however, looks different. For these reasons, The Center Square will examine private institutions separately.

While each school has different funding structures, student bodies, and fields of excellence, all rely on federal taxpayer-funded grants to conduct research that gives them global reach.

Pounds used enhanced AI to find more than $245 million in federal grants received by Penn, more than $263 million by Penn State, and more than $79 million by Pitt between 2020 and 2025.

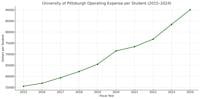

At the same time these grants were awarded, operating costs at each of the public schools rose dramatically despite enrollment decreasing, stoking fears that the influx of research funding comes with an administrative burden that can only be sustained through more government spending. Meanwhile, tuition has continued to rise.

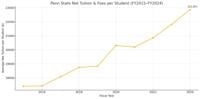

A decade ago, Penn State charged in-state students $17,514 for tuition. By the 2024-25 academic year, tuition rose nearly 17% to $20,644. Corresponding enrollment dropped about 10%, from 97,500 to 88,000 in 2024. The university announced in February that it would close seven branch campuses due to the declining enrollment.

The University of Pittsburgh’s trends look slightly different: while enrollment over the last decade has climbed about 11%, from 27,000 to just under 30,000, it’s not been a steady trajectory. Since 2019, the institution has lost 2,000 students.

Tuition varies at the university depending upon degree but ranged from $17,000 to $21,000 for in-state students in 2015. A decade later, the scale is $20,000 to $36,000.

At UPenn, roughly 28,000 students paid $42,000 annually for tuition in 2015. In 2024, just over 29,000 students paid almost $61,000, a 45% increase in costs versus a 3.5% rise in enrollment.

With high stakes for both taxpayers and students, The Center Square dug into the research funding process to parse out any influence the federal money may have on the overall picture.

But AI alone could not adequately judge the scholarly merit of the projects undertaken by these schools. To demonstrate AI’s capabilities, Pounds asked her tools to analyze what the most questionable grants in the data were. Enhanced AI returned several project descriptions.

One was $1 million awarded to the University of Pittsburgh to study the rapid evolution of the determinants of bee species' coexistence. This grant was justified "by its potential to enhance our understanding of ecological processes, which could inform future conservation strategies and environmental policies."

Another was a more than $296,000 epigenetic study of house sparrows, one that had already outpaced many of the included studies by being cited in multiple peer-reviewed journals, a key metric enhanced AI was using to gauge a study’s “worthiness.”

More InformationPenn State University received more than $263 million in federal grants from Biden-era spending bills such as the $280 billion CHIPS and Science Act and the more than $700 billion Inflation Reduction Act. Many of those grants went to fund research in the medical field. Here are a few of the others:

• $2.58 million to study a coordinated one health approach to risk assessment of hemorrhagic fever viruses in West Africa.

• $673,685 to study the unintended consequences of specific immigration enforcement policies, which could guide more effective and equitable policy development.

• $300,000 to advance resilience in low-income housing using climate change science and big data analytics.

Allowing AI to analyze the data using objective metrics like citation counts was not completely sufficient. According to Dr. Andrew Read, senior vice president of research at Penn State, most research in scientific fields takes years before significant breakthroughs are published, and, in most cases, grants awarded since 2020 are still in the earlier stages of development. Ultimately, whether the Biden-era grants were worth the price tag won’t be known for perhaps a decade, Read said. And even then, it will be a subjective determination.

Meanwhile, doctoral dissertations – like one researcher’s more than $63,000 ethnographic work on indigenous dance, a second item questioned by AI – have the primary purpose of preparing a graduate student for a lifetime of scholarly work. This project, too, had associated citations already. While we don’t know how the funds were specifically allocated, we do know the price tag of this grant would cover less than two years of graduate study for most Pitt students or less than a year of travel and living expenses.

More InformationThe University of Pittsburgh received more than $79 million in federal grants from Biden-era spending bills such as the $280 billion CHIPS and Science Act and the more than $700 billion Inflation Reduction Act. Many of those grants went to fund research in the medical field. Here are a few of the others:

• $480,000 award to study countering COVID-19 misinformation via situation-aware visually informed treatment.

• $397,549 grant to develop a 700,000 year record of tropical precipitation, evaporation and temperature from Lake June sediments and mineral deposition in Peru.

• $313,450 award to explore how teaching and learning occur within two native Alaskan dance and drumming groups are integral indigenous education activities, with culturally distinct traditions across the Arctic.

Demanding that level of “productivity” from a student demonstrates the “publish or perish” model of academia that graduates will soon enter, according to a retired academic researcher from the National Association of Scholars, Dr. J. Scott Turner.

Turner serves as the association’s director of diversity in the sciences project. He spent 40 years probing evolution and ecology studies, most recently at the SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry. With more than 100 scientific articles under his belt, he told The Center Square that academic research has shifted from discovery to productivity, though the latter lacks discernible metrics beyond grants acquired and research published.

And, he says, it has led many within the academic community to agree there’s a problem with the way the United States spends taxpayer money on and conducts research.

Turner said the end of World War II marked a turning point in which scholarships funded internally by institutions or externally by patrons gave way to a booming American scientific industry that was fueled by an influx of foreign scholars, generous federal spending and a desire to outperform the Soviet Union.

He believes the modern competitive grant process has fundamentally shifted science away from discovery and into a position where researchers are constantly focused on justifying and funding their work.

“It’s numbers and papers,” he said. “It’s numbers of the amount of grant monies that you brought in, numbers of students that you have trained, all these kinds of metrics that scientists are now judged by,” he said. “And if you take a real deep dive into the relationship between production and discovery, it’s a very nebulous connection, and so what you have done is you’ve changed basically the landscape of incentives and disincentives that scientists can build careers on.”

Turner says that when researchers get that funding, it comes with implicit strings. Political entities like the National Security Agency or the National Institute of Health, which award many grants, naturally have political aims. Those aims, he says, are reflected by which projects are funded in the highly competitive landscape.

Examples of this are easy to find from both leading political parties. Turner pointed to the Diversity, Equity and Inclusion requirements, which he deemed unnecessary for certain grants, that have proliferated under Democratic administrations.

Worse still, he said, many researchers, under pressure to keep money flowing into universities will tailor grant applications to meet those requirements, even if the underlying research has little to do with it.

Across the aisle, Education Secretary Linda McMahon ruffled feathers in the academic world last month when she told CNBC, “Universities should continue to be able to do research as long as they're abiding by the laws and in sync, I think, with the administration and what the administration is trying to accomplish,” making the thread between federal funding and academic priorities both explicit and conditional.

In a conversation with The Center Square, Penn State's Read offered a different perspective.

“Historically, the reason that the universities got so tied in with the federal government funding was because of the concern by both the federal government and the universities after the second World War about the disproportionate influence of industry,” he said.

He pointed to studies bankrolled by private industry, which tend to absolve their products of harm, like soda companies funding research that says the sugary beverage is not bad for children’s health. The federal government could, in theory, more impartially reflect the broader interests of Americans.

This very concern was recently echoed in a report from Secretary of Health Robert F. Kennedy’s Make America Healthy Again Commission, which depicted a world of academic publishing bought and paid for by companies eager to deflect blame for the damage caused by chemicals like food dyes and pesticides. The report contended, however, that it was private industry and not government regulation that could remedy the problem of private interests.

Some of the research done at schools like Penn State does involve partnerships with private companies, and in those cases, parties work with clear goals in mind, like developing a specific type of drug or technology. This is a strong distinction from the open-ended curiosity of individuals in a past lauded by Turner and other dissenting scholars, which led to happy accidents like the discoveries of X-rays and penicillin.

For Read, what research looks like largely comes down to the motivation of the individual researcher in question.

“We've got people who want to do fundamental quantum mechanics. That might end up in a quantum computer in 10 years time, but they don't care about the quantum computer,” he said. “They’re just super excited about the underlying physics.”

Much of the research at Penn State and Pitt is unmistakably bigger than a single scientist plugging away at quantum computation. For instance, last August, Penn State was awarded a nearly half-million-dollar taxpayer-funded grant from the Department of Energy to support an interdisciplinary team studying thunderstorms. The research may one day provide a more sophisticated understanding of dangerous weather patterns that could cause extreme flooding, damaging winds and tornadoes.

UPenn received $3.4 million to develop the COBALT app, which assesses the mental health of health care workers in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The success of the open-source model will soon see Dartmouth and New York University operating a similar platform.

And in Pittsburgh, a $4.2 million grant allowed researchers to study postmortem brain tissue samples to better understand sports-related injuries and neurological diseases like Alzheimer's.

The Center Square found few scientists willing to speak up about their work or their funding. Read was the only representative of any of the three schools researched who spoke with The Center Square despite numerous attempts to get others to comment.

Turner and Read agree the larger the school’s portfolio of research funding is, the more overhead costs are required to support it.

Read says that the research done at Penn State brings in the funds needed to allow for the growth of its operations. What he sees as an “existential threat,” on the other hand, is new caps on the overhead costs researchers are allowed to claim in federal grants. In February, the National Institutes of Health lowered the cap to 15% of overall funding, meaning a far smaller portion of each grant will go toward schools' administrative costs. NIH lowered the cap to assure more taxpayer dollars went to the actual research itself on not to support administrative overhead.

Turner says lowering these caps should do nothing to harm the research itself. Rather, he believes the reduction will curb "administrative bloat" that has allowed universities to grow even as student bodies shrink.

“It results to actually a fairly small proportion of their total financial picture, of their total spending,” he said. “And If you look at some of the things they are doing with their money, that’s something reasonably good financial managers should be able to weather just fine.”

But Read told The Center Square that 15% will be untenable in the long-term, saying the 26% they've been able to allocate to overhead is barely enough to keep up with demanding federal regulations.

This slide provided by Penn State illustrates indirect costs within the grant funding process.

Staff in the Office for Research Protection at Penn State has grown from a single person in 1991, when the current 26% cap on administrative overhead was instituted, to 62 people in 2024.

Skeptics point to Penn State’s $4.78 billion endowment, a figure that has more than doubled since 2016, to close the gap. Pitt’s $5.8 billion endowment has grown by 66% in the same span.

Read says that most of the school’s endowment is made up of funds committed for specific costs like student scholarships, which can’t be used for other purposes. He says it’s not the responsibility of PSU students to cover the costs of a federal regulatory burden, so the school would not raise tuition to cover the difference. Instead, they’d have to look to the state or make hard choices about cost-cutting moving forward.

The threats of cuts are sending some scientists running in what some fear is an American brain drain not dissimilar to Europe’s in the 1930s and 40s. Read said even patients are following them to places like China, where they can receive treatment on the cutting edge of medicine.

“When I was young, the dream of being a scientist was to be a scientist in America where the best science was done and supported, and now we lost two candidates for positions to Singapore just recently,” said Read, who is from New Zealand. “I think every one of our research stars is looking at options abroad.”

But Turner eschews what he calls the “mass hysteria” from universities.

“There’s definitely a challenge here that the Trump administration is posing to universities, but the actual problems don’t match the hysterical rhetoric that’s surrounding it,” he said. “And it’s ignorant of the fact that there’s quite a bit of money out there besides what’s coming from the federal government to actually fund research.”

Such a shift could pose an opportunity to shake up a broken system and cut the strings that keep scientists more focused on output than import.

"This doesn't mean you're not getting discovery right now," said Turner of the current research landscape, who believes that the pace of discovery is "indifferent to or not at all related" to spending. "I personally am suspicious of any kind of thing that says, 'We're going to throw all this money at science, and we're going to get discovery out of it.'"