ICE Has Created a ‘Ghost Town’ in the Heart of Chicago

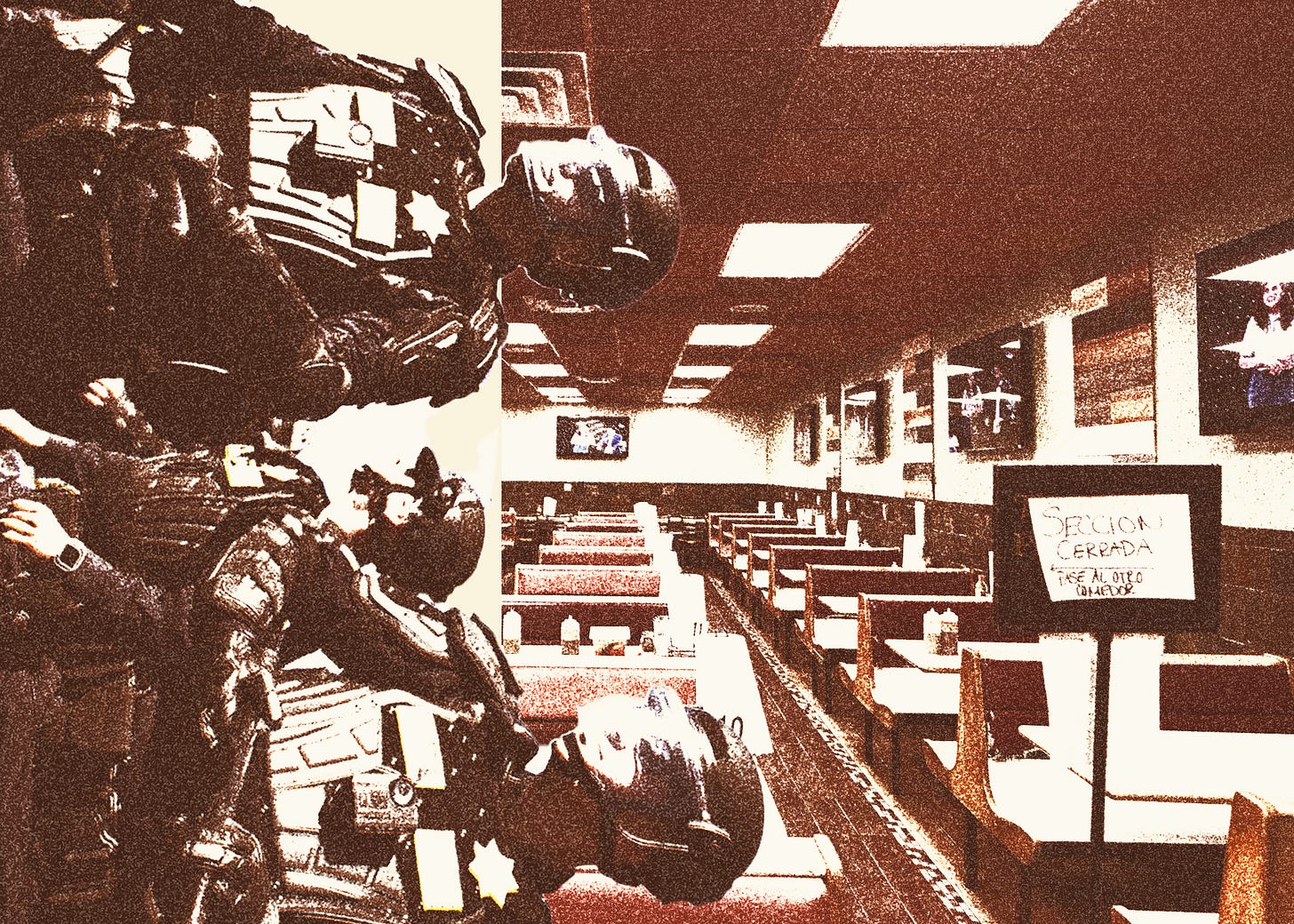

Carniceria Aguascalientes, a local Little Village dinner spot, was empty in October when The Bulwark visited. The lack of patrons was a stark contrast to the summer before their community feared persecution. (Photo by Adrian Carrasquillo / Composite with GettyImage by Tayfun Coskun)

Carniceria Aguascalientes, a local Little Village dinner spot, was empty in October when The Bulwark visited. The lack of patrons was a stark contrast to the summer before their community feared persecution. (Photo by Adrian Carrasquillo / Composite with GettyImage by Tayfun Coskun)Chicago, Illinois

DHS’S IMMIGRATION ENFORCEMENT ACTIONS continue to land like hammer blows on communities across the United States. Families are being torn apart, protesters are catching pepperballs, businesses are at risk, and, increasingly, entire neighborhood economies in areas with large Latino populations are grinding to a halt.

The worst consequences occur when these different aspects of the Trump administration’s deportation regime overlap. Case in point: Chicago’s food scene, specifically the capital of the Mexican Midwest, Little Village, where I got both a firsthand look at the compounding harms of ICE’s actions and the best gorditas I’ve ever had in my life.

The first sign of how different things are come well before you take a bite of the gordita. It’s when you look around and realize that there is now an eerie emptiness to a once-vibrant place.

As I pulled into Little Village for dinner with some local Chicagoans, we experienced no traffic and had our pick of parking spots. “Traffic used to be bumper to bumper for decades and start blocks away, I’ve never experienced it like this,” Chicago food writer Ximena N. Beltran Quan Kiu told me. In a TikTok about the neighborhood, she noted that Little Village is the second-largest shopping district in the city after Michigan Avenue, which is home of the “Magnificent Mile” of luxury stores.

Our destination that day last month was Carniceria Aguascalientes, which sits on the main thoroughfare of 26th Street. We passed through a glittering Mexican grocery store at the street side to get to the large diner-style restaurant lined with tables and booths. Only two or three of roughly thirty tables were in use when we sat down. As we enjoyed our food, the largely vacant dining room became less and less comprehensible.

When I told our friendly waitress, Michelle Macias, 24, what I do and why I was in town, she was eager to share what had happened to the restaurant. Aguascalientes, a staple of “La Villita,” has welcomed customers for half a century. But lately, its business has plummeted. Sales are down a staggering amount: more than 60 percent compared to last year.

Everything has been turned on its head, Macias explained. While in past years Fridays, Saturdays, and Sundays were bustling, lately Mondays have become the restaurant’s busiest day—perhaps a result of people trying to avoid the usual crowds of the weekend. The restaurant announced this year that it would be closing an hour earlier, a money-saving measure. And as I had noticed, there’s now parking readily available, a fact that shocks longtime patrons accustomed to the gridlock that formerly surrounded the popular eatery.

The bleak reality facing Carniceria Aguascalientes weighs on its forty employees—especially Macias, whose parents own the restaurant.

As I took it in, I couldn’t help but think back to when Trump’s mass-deportation policy was just getting underway, and the many conversations I had then with Democratic lawmakers who wondered aloud about where we would be in three years. Forget three years: In the Latino enclaves of Little Village, and in Back of the Yards, in Pilsen, and on the North Side, they’re wondering how they will get through the next three weeks.

“Everyone is staying home, everyone is scared,” Macias told me. “There’s so much uncertainty. COVID was bad, but this is way worse.”

Carniceria Aguascalientes back in June full of patrons. At right, Michelle Macias, server and daughter of the restaurant owners. (Photos by Kristen Mendiola and Adrian Carrasquillo)

Worse, perhaps, but still not impossible.

Chicagoans are coming together, not just to try to protect immigrants or brown U.S. citizens from being taken by masked federal agents but to spend their money at the businesses being affected by ICE activity. What began as a trickle of support is growing into a serious movement, although it remains an open question whether it will be enough for struggling small businesses and restaurants to successfully weather the ICE storm.

Beltran Quan Kiu, who has written for Food & Wine and Bon Appetit, has been at the forefront of advocating for these struggling restaurants and businesses. For an event she held at Aguascalientes in June during the James Beard Awards weekend, she brought dozens of people to the restaurant from as far away as Boston, Tucson, Asheville, and Kansas City.

But there are limits to how much help you can give restaurants like this in the face of ICE’s depredations. These aren’t nonprofits with websites set up to take donations, and even GoFundMe campaigns can be difficult to vet. At the end of the day, Beltran Quan Kiu said, the best way for people to help businesses like Aguascalientes is to patronize them.

“Do not underestimate how powerful it is to go and to see it yourself,” she told me. “Little Village is the canary in the coal mine—you have five hundred businesses, which are 77 percent Latino, so there’s no white, black, or Asian communities to offset the decrease in foot traffic.”

Beltran Quan Kiu made this case last month in a piece for Chicago magazine. It caught the attention of famed Chicago restaurateur Rick Bayless, who shared the article on Instagram and implored his followers to “visit the great restaurants in Pilsen, Little Village and other predominantly Latino neighborhoods.” Chicago chef and James Beard Award winner Jason Hammel also shared the article on Instagram, and Joe Flamm, the chef and owner of two Chicago restaurants, visited Aguascalientes and posted about his meal there, as well.

James Beard Award semifinalist Marcos Carbajal owns Carnitas Uruapan, which has been around since 1975, with locations in Pilsen, Gage Park, and Little Village. In a heartfelt video this week, he thanked the new customers from across town and the catering orders that came after the Chicago magazine piece. He said it took a lot for restaurants like his to ask for help and mentioned how tense it was when ICE descended on Little Village outside his restaurant, detaining U.S. citizens, pepper-spraying bystanders in the face, and causing a traffic clusterfuck.

“I’d really like to thank everyone for coming out, ask them to continue to come out to the neighborhoods—not just Little Village, but Pilsen, Gage Park where other restaurants are, generally all these areas being targeted right now,” Carbajal said. “Eat in our establishments, and then go out into the neighborhoods, support a street vendor, go down the street, support our neighbors, stick around and make a day out of it, and hopefully we will be in a better place and . . . have all this behind us soon.”

This is the sort of encouragement and organization it will take for businesses to survive the chaos and fear of the ICE occupation. As of yesterday, Border Patrol was reportedly back in Little Village, continuing to choke the local economy, and validating people’s reasons for staying home, U.S. citizen or not.

WHEN I RECENTLY WROTE about the work of Protect Rogers Park, a community group that fights ICE in its North Side neighborhood, I mentioned an episode in which community members were thrown into confusion and fear when they could not locate the local tamalero. Initially, they believed he had been taken by federal agents. It turned out to be a false alarm: A cheery employee at a local taqueria told us he’d simply gone home for the day. But when I asked that same employee how her business has been doing since ICE set up shop, her eyes darkened. As a lone customer sat quietly eating nearby, she told me 50 percent of their business had disappeared because of the fear and uncertainty.

Sitting for lunch with Protect RP head Gabe Gonzalez at nearby La Casa Vieja on the Clark Street business corridor, I asked the owner’s son how the restaurant was faring. He, too, told me half of their business has gone out the door with the arrival of ICE.

“There are no construction workers coming,” he said. The men used to come in daily, and each group would spend around $100.

Nearby at Ciudad de Hidalgo, owner Freddy Martinez, 54, told me business is down 50 to 60 percent.

“The Latinos have stopped coming,” he said. “We need more people, everyone you can bring is good for us.”

Restaurants are not just asking people to help them, though. They are paying it forward, offering free meals to people staying home out of fear of ICE.

When local community group Increase the Peace connected last week with La Bahia de Acapulco, a restaurant in Back of the Yards, to support homebound community members, they started an initiative to offer 150 meals for local residents. But when the group put out a call to find people who needed the help, they got more than double the expected requests. By the morning after they started publicizing the free meals, they had received requests for 500. Mayra Macias, a local Democratic organizer and volunteer with Increase the Peace, told me that in the end, they were able to raise $3,800 to feed nearly 600 people.

And theirs was hardly the only project of its kind. On Halloween, she said, some restaurants gave out food instead of candy. Everyone is aware of the need—of both the businesses suffering from ICE and the prospective clients who now won’t leave their houses to get food. They are eager to help out.

“Mom-and-pop shops are stepping up and feeding their communities in part because the community has shown up for them and stepped up for them to make sure we’re taking care of each other. It’s heartening to see,” Macias said. “Then to look at what local businesses are doing, it’s beautiful and touching and gives me hope about what comes after ICE leaves Chicago with this infrastructure built and our community solidified.”