The pernicious myth that America doesn’t win wars | Blaze Media

False narratives have a way of being taken as fact in popular understanding. After years of repetition, these statements calcify into articles of faith, not only going unchallenged, but having any counterarguments met with incredulity, as though the person making the alternative case must be uninformed or unaware of the established consensus. Many people simply accept these narratives and form worldviews based on them, denying the reality that, if the underlying assumption is wrong, then so are the decisions that flow from it.

One narrative that has taken hold among many since the humiliating end to the war in Afghanistan is that the U.S. military doesn’t win wars, or that it hasn’t since the end of World War II. This critique of the armed forces, foreign policy, or use of force has become an ironclad truth among many who use it as a starting point to advocate their own preferred change.

The United States military has had plenty of successes since World War II and, in fact, has suffered only a small handful of definitive losses in that time.

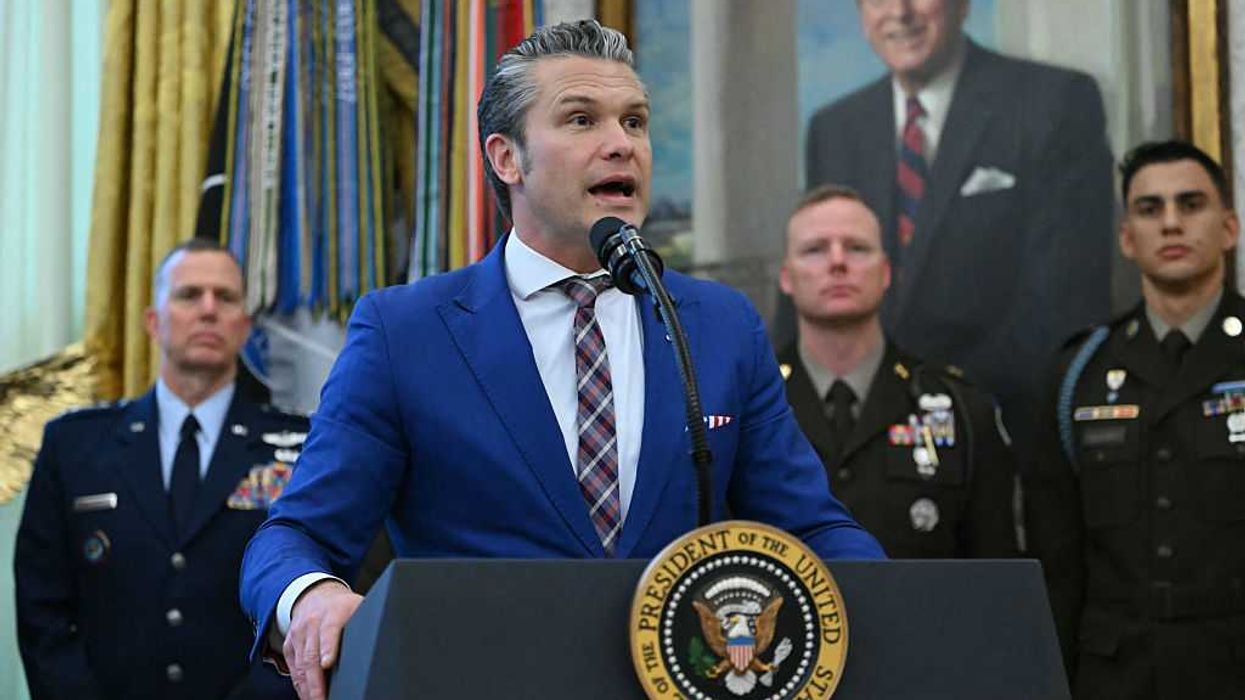

Advocates of War Secretary Pete Hegseth’s vision for the military have echoed it: “The military had grown weak and woke, so we need to change the culture, ignore or at least diminish adherence to legal restraints, and remake the composition of the military.” Restrainers, isolationists, and America Firsters have joined the chorus: “America has given up blood and treasure on stupid wars in which we were failures.”

There is only one problem with this understanding, and more importantly, its use as a baseline from which to derive policy prescriptions — it isn’t true at all.

Ignorance of warIt reflects a misunderstanding of how America has used force and what we have and haven’t achieved. And unlike many misunderstandings about American defense, this one isn’t solely by those with little familiarity with what the military does; the view has taken hold among many who should know better. There are several reasons for belief in the fallacy.

First, there is ignorance of what a war is, or at least not having a common definition of it.

For the pedants, one could point out that the United States has not been at war, by strict definition, since 1945. However, this isn’t relevant to the topic at hand because if the United States has not fought a war since 1945, then by this definition, we also haven’t lost one. In fact, the United States has declared war many times: the War of 1812, the Mexican-American War, the Spanish-American War, and the World Wars, yet we have engaged in armed conflict significantly more often than that.

So for the purposes of this debate, we can reflect upon the United States using force to achieve foreign policy objectives. With this more expansive definition, then Grenada is just as much of a war as World War II (although the latter certainly is a source of more pride than the former).

Second, there is ignorance of the number of conflicts in which the United States has been involved. Americans tend to have short memories and often pay less attention to events beyond the water’s edge. Many are largely ignorant of ongoing, smaller operations being conducted in their name. (Remember the shocked response to the Niger incident when many people, including congressional leaders, announced their ignorance of U.S. presence there?)

This phenomenon is exacerbated by the passage of time. How many Americans are aware of our involvement in the Dominican Civil War in 1965? Or the various conflicts that made up the Banana Wars?

RELATED: Turns out that Hegseth’s ‘kill them all’ line was another media invention

Third, there is ignorance or misunderstanding of the outcome of those wars. Our perspective has been skewed, likely due to the recent history of the embarrassing and self-inflicted defeat in Afghanistan, the messy and confusing nature of the war in Iraq, and the historic examples of very clearly defined wars with obviously complete victories.

There was no ambiguity in the World Wars. The United States went to war with an adversary nation state (or coalition of them), fought their uniformed militaries, and ended these with a formal surrender ceremony abroad and victory parades at home. But this is not the norm, neither for American military intervention nor for conflict in general.

Most of American military history does not look like these examples — conflicts that are large in scale, discrete in time, and definitive in outcome. Some of our previous interventions have been short in duration and were clear victories but smaller in scale (e.g., Grenada and Panama). Some have been clear victories but incremental, fought sporadically with fits and starts and over the course of years, if not decades (e.g., the several smaller conflicts that are often lumped together under the umbrella of the Indian Wars).

Win, lose, drawBut then there is another category — one in which the conflict results in a seemingly less satisfying but mostly successful result, sometimes after a series of stupid and costly errors and sometimes after years of grinding conflict that ends gradually rather than with a dramatic ceremony.

The Korean War, often described as a “draw” because the border between North and South Korea remains today where it was before the beginning of the war, had moments of highs and lows, periods where it seemed nothing could prevent a U.S.-led total victory — only to see the multinational force squander its advantage (e.g., reaching the Yalu River) and moments where all seemed lost, only to escape from the jaws of defeat through audacity and courage (e.g., Chosin Reservoir, Pusan, Inchon).

When President Truman committed U.S. forces as part of the U.N. mission to respond to communist aggression, the stated intent was to assist the Republic of Korea in repelling the invasion and to maintain its independence. South Korea still exists to this day. The combined communist forces of the PRK and CCP were prevented from achieving their aims by American military power.

We have a much more recent (and undoubtedly more controversial) example of a misunderstood success. Many of those who ballyhoo about America not winning wars point not only to the failure in Afghanistan but also to the recent war in Iraq. The Iraq War was many things — initially fought with great tactical and operational brilliance, then sinking into lethargic and incompetent counterinsurgency, then adapting to local power structures, and of course, initiated under pretenses we now know to be incorrect. But it was not, despite the ironclad popular perception, a military failure.

The military set out, with the invasion of 2003, to defeat the combined forces of the Iraqi Army and Republican Guard and remove the Ba’athist government from power. We achieved that goal. Once in control of Baghdad, the U.S. faced a new threat — one of a growing and complex insurgency that we had failed to anticipate. American forces under Ricardo Sanchez, and continuing under George Casey, seemed perplexed and frustrated by a conflict they had not come prepared to fight, nor that they adapted to. For years, despite the insistence of many military and political leaders, the war was not going our way as American casualties increased month after month.

But by 2008, the Sahwa — the movement of Sunni tribal militias aligning with the U.S.-led coalition and the government in Baghdad — and the American efforts to adapt to a more effective counterinsurgency strategy were turning the tide, to the point that by 2010, the violence in Iraq had largely subsided.

The government the United States helped bring about in Baghdad to replace Saddam Hussein endures to this day but not without difficulties. In his 2005 “National Strategy for Victory in Iraq,” George W. Bush defined victory in the long term as an Iraq that is “peaceful, united, stable, and secure, well-integrated into the international community, and a full partner in the global war on terrorism.” By continuing to maintain a relationship with Iraq, we are helping shape this long-term result, just as we did as we helped postwar Germany and Korea maintain security and political stability.

Due to the oppressive steps of a flawed prime minister, American desire to recede from presence and oversight in Iraq, and a compounding effect of spillover from the Syrian Civil War, there was the need for further American assistance in defeating the threat from ISIS, but defeat them we did — another success for the American military.

The Iraqi government also has close relationships with our Iranian regional rivals, as many of the local Arab countries do based on proximity. But just as the need for the 2nd and 3rd Punic Wars does not change the fact the 1st Punic War was a Roman victory, the war against ISIS does not change the fact that the United States accomplished the goal of deposing and replacing Saddam Hussein. Likewise the fact that the Soviet Union gained influence over Eastern Europe does not change the fact that World War II ended in a definitive defeat of the Nazis.

What does victory look like?None of that changes a separate question, however — whether the war was worth it. But that was a political decision and one that does not negate the truth that the U.S. military first defeated the Iraqi military in a decisive win and then quelled a grinding insurgency in a less decisive way.

Just because a victory isn’t total doesn’t mean that the military fighting it lost. The War of 1812 was a victory, despite the fact the U.S. failed to achieve its maximalist goals of incorporating Canada but did achieve the goal for which the war was fought — rejecting British attempts to deny American sovereignty. World War II was a victory, despite the fact it set conditions for the Cold War and communist oppression. Korea was a victory, despite the fact we did not unify the Koreas under the democratic South. And Iraq was a victory — a poorly decided, stupidly managed, and possibly counterproductive long-term victory.

RELATED: Trump forced allies to pay up — and it worked

When viewed in this way, the United States military has had plenty of successes since World War II and, in fact, has suffered only a small handful of definitive losses in that time — Vietnam, Iran (Operation Eagle Claw), Somalia (1993), and Afghanistan — with the temporal proximity of the latter and the fact that two of these were also America’s longest conflicts, helping to warp the public’s understanding of our military effectiveness.

None of this is to say that America should not take a harsh look at our recent military efforts and seek continuous improvement. Grenada, as I have mentioned, was a victory but an incredibly embarrassing one that was likely only successful because we fought a backwater Caribbean country with a population of less than 100,000. The hard lessons learned by examining the disasters, mistakes, and close calls from Operation Urgent Fury helped reform the military into the globally dominant force that defeated the world’s fourth largest army in 100 hours less than a decade later.

Americans should not look at our military through rose-colored glasses, chest thumping as we chant “USA” and insisting that no other force can land a glove on us. But neither should we allow the false narrative of failure to take hold. We should be clear-eyed about what our military has accomplished, can accomplish, and the costs, risks, and potential gains in using force. Armed conflict will remain a necessary tool for the United States. We need to adapt our military to meet and defeat the challenges of the future, and we need to balance and incorporate military power into our global strategies appropriately — but that will not happen if we do it based on an incorrect understanding of the past.

Editor’s note: This article was originally published by RealClearDefense and made available via RealClearWire.