There Is No Message

Robin Westman—born Robert Westman—stormed the Annunciation Catholic Church in Minneapolis last week, sending rifle fire through the stained glass until color and light collapsed into dust. The attack left 116 casings scattered across the floor, joined by a pistol and three shotgun shells that left two children dead and several others breathing but mangled.

The internet lit ablaze with theories in response. From every corner came scavengers of meaning, stringing the massacre into ideologies like beads on a broken rosary. Within hours, Westman was painted as a transgender killer, a far-right fanatic, a Catholic hater, a Trump hater, a Jew hater, a vessel for every narrative at once. Each new fragment contradicted the last, until the portrait resembled not a man, but a glitching specter assembled from digital static.

The incoherence rendered the shooter as a mouthpiece for the web’s pandemonic underworld, speaking its language of violence without reason and destruction without creed. By weekend’s end, even The New York Times could only surrender to the void: “What motivated the church shooter? We may never know,” said the paper.

But when a friend sent me images of the shooter’s weapons, I couldn’t help but hatch a tentative theory. The photos showed inscriptions carved into Westman’s rifles and clips, messages that looked hauntingly familiar, as if dredged from some half-remembered slumber through my self-destructive internet deep dives.

“O9A strikes again,” commented my friend.

I’d covered the Order of Nine Angles, a satanic neo-Nazi terror network, a month prior, in Tablet. The secretive right-wing group was born in the United Kingdom in the late 20th century and has since become ideologically influential globally, inspiring such prominent groups as the satanic terror and cybercrime network 764. Examining the photos of Westman’s rifles, where one Glock’s handle bore the inscription “666 + 79417,” I could see that the first number was obvious enough. It was the beast’s cipher, a crude invocation of Satan. But the second was less clear. To me, it echoed the Hitlerian satanic sect 764. In Westman’s scrambled mind, such numbers might have blurred together, mistranslated into this jagged cipher. Another weapon bore words far less ambiguous: “Jew gas.” The phrase hissed with genocidal intent, its venom aligned with the Order of Nine Angles’ doctrinal worship of Hitler.

Westman’s final creed, etched in steel, was a paradox whispered through bullets: There is none.

The next inscription, etched into the chamber of a Glock, read with chilling irony, “There is no message.” Again, the Order of Nine Angles came to mind. The group’s writings—largely attributed to the extremist David Myatt under the alias Anton Long—describe history as an “aeonic evolution,” a cycle in which ideas emerge, take hold, and collapse into banality through repetition. At the end of such an aeonic phase, meaning itself dissolves, and only an act of spectacular bloodshed can rupture the cycle and give birth to something new. If there were truly “no message” to be found, then perhaps Westman believed the phase had ended and that it was his role to close the epoch in violence so that another might begin.

“There is no message” also recalls, uncannily, the phrase used by the apocalyptic sect known as the Guilty Remnant in Damon Lindelof’s The Leftovers—a cult that abandoned families, cloaked themselves in white, chain-smoked like penitents, and embraced silence to embody their doctrine that meaning itself had collapsed. In that series’ world, 20% of humanity vanished without explanation, a disappearance so vast it shattered history into a before and an after. This nihilism found a cruder echo on a magazine clip, engraved with the words “Fuck everything that you stand for”—a line likely torn from the Iowa nu metal band Slipknot’s “Surfacing.”

In Westman’s deranged imagination, it is easy to see how such logic might transmute into violence: that the supernatural erasure of billions could be mirrored, however grotesquely, in the violent erasure of a few. His final creed, etched in steel, was a paradox whispered through bullets: There is none.

It seemed clear to me that the Order of Nine Angles, with its labyrinthine creed of chaos, bloodshed, and transcendence, might have been the connective tissue threading through the killer’s mind—a violent occult ideology the legacy media has neither the language nor the framework to comprehend, let alone illuminate with anything resembling meaningful commentary.

In my earlier Tablet article, “The Nine Angles,” I examined the O9A-influenced cybercrime collective 764, a network tied to sextortion, child trafficking, and other acts of violence. But O9A itself has never been a proper organization; it is less a group than a violent esoteric ideology—bewildering, extreme, and luridly aesthetic—woven through Myatt’s philosophical tracts and occult “rites.” This makes it nearly impossible to pin down how O9A could ever function as a criminal body in the conventional sense. When so-called O9A-linked arrests are made, they rarely involve initiates of any formal order. Instead, they are individuals or collectives steeped in O9A’s influence, as in the case of 764. For that reason, I would not claim Westman was a member of O9A—only that he might have been possessed by its shadows.

O9A beliefs can spiral into psychological warfare, ensnaring angry, lonely, alienated young men. “It’s all an op used to justify a bloated security state,” one occult writer whispered, as if speaking from behind a crackling radio in some unseen room. Rumors swirl that Myatt himself could be a “fifth-generation warfare asset,” seeding vulnerable minds with extremist ideologies that twist and multiply, pushing them toward acts of violence that ripple through the simulacra of information networks and time itself. Whether this is to provoke heavier crackdowns on the right or to tilt discourse on some obscure corner of reality is almost immaterial. The machinery hums regardless, unseen and inevitable, leaving behind only chaos.

More on the Order of Nine Angles

Westman might well have been drawn into this shadowed web online, targeted by spooks and dangerous actors who deliberately scrambled his already-struggling mind with a chaotic tangle of conflicting beliefs—only to finish the work with the O9A doctrine, driving the final nail into the coffin of his sanity.

An X thread from the account psychsomatica seemed to confirm the pattern I’d sensed: “The Minneapolis shooter is an O9A/764 terrorgram right-wing grooming victim.” The post vanished almost immediately, erased by moderators, but the echoes persisted. Another X user claimed that Westman “interacted with 764 on Discord servers.” O9A and its satellites live in the shadow veins of the internet—Discord, Telegram, X—pulsing with recruitment, ritual, and propaganda.

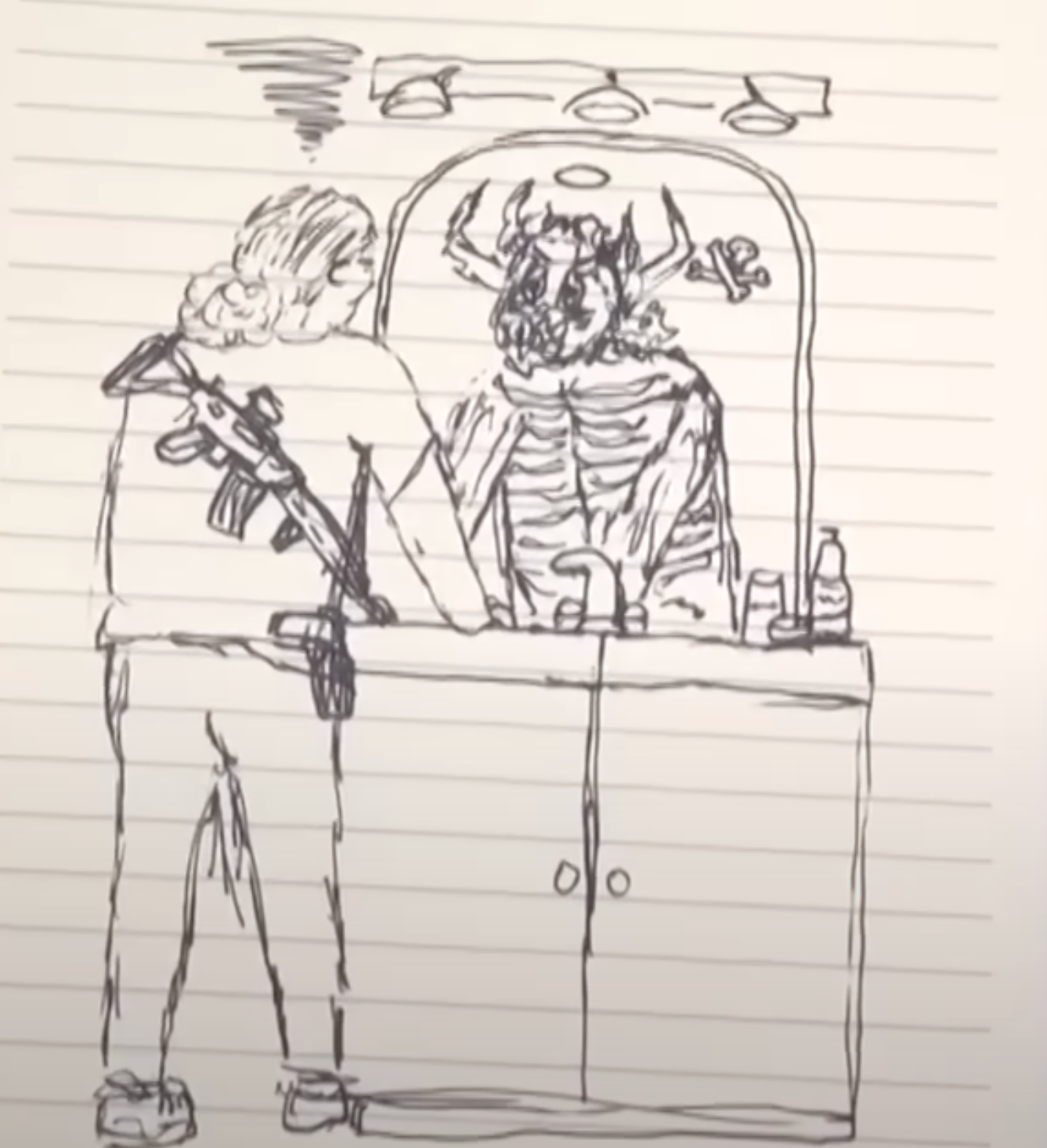

It should be said that, for now, all of this remains highly speculative; Grok still labels every X post linking Westman to O9A as unsubstantiated. Yet poring over the shooter’s journals only deepens the murk. The journals speak to his anti-Catholicism, another hallmark of O9A—because, of course, they are satanists. Among the pages lies a diagram of Annunciation Catholic Church, attack plans, and passages saturated with nihilistic despair: musings on imagined cancer, the impossibility of turning back, the sense that his path was irredeemable. The writings pulse with the same bleak, aeonic fatalism central to the O9A worldview, a doctrine in which destruction and despair are not accidents, but instruments of a cosmic cycle.

Westman’s more than 200 pages of handwritten notes—some in Cyrillic, as if to bury their meaning—also reveal a lifelong obsession with mass shooters. Names leap from the pages: Adam Lanza of Sandy Hook, 2012; Robert Bowers of the Tree of Life Synagogue, 2018; and others, ghosts of violence catalogued with chilling devotion.

Analysts, including Amy Cooter of the Institute for Countering Digital Extremism, describe Saints Culture as an online cult of reverence, in which mass shooters are transfigured into “saints” within shadowed communities. On Discord and Telegram, the subculture churns memes, artwork, and manifestos like ritualistic incantations, elevating figures such as Lanza or the Christchurch shooter into something almost mythic, portraying their violence as transcendence itself. Westman’s journals echo this fevered devotion, reflecting the hours he spent watching shooting videos, scribbling notes, and obsessively fretting over FBI attention. The term saints itself seems a dark incantation, lifted from far-right and neo-Nazi rhetoric, canonizing these killers as martyrs to a cause defined not by creed, but by erasure.

As I noted in my previous article, Hitler is revered by O9A adherents as the apex saint, if such a term can even suffice; the Holocaust is seen as a singular, world-altering act of violence, one that reshaped the course of history and the very way we perceive time and consequence. Shooters like Westman, under the sway of these beliefs, are not entirely “wrong” in their morbid worldview—at least within this macabre ethos—in elevating killers to the status of “aeonic saints.” Who could deny that Columbine inaugurated a new aeonic phase? On that day in 1999, when Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold murdered nine classmates in Colorado, one era ended—the days when my parents would buy me Marilyn Manson and Eminem CDs—and another began: a world where I had to pass through a metal detector to enter the fifth grade.

In truth, I have no doubt that Westman had been exposed, at the very least, to O9A philosophy—and quite possibly to 764-linked child sex criminals—during his wanderings through the labyrinthine layers of Web 2.0, 6.0, and 9.0. The more haunting question is this: To what end was this young man driven, pushed into a vortex of psychosis and violent mania, until he crossed the ultimate threshold, shattering our most sacred taboo by murdering children?

The terrifying answer likely circles back to what I said earlier: nothing. Those online who exploit these beliefs—if they genuinely adhere to O9A—see taboos as nothing more than the brittle husks of a dying civilization. To violate them is to turn the machinery of destruction against the culture that created them, to tear down the old and summon something new.

There is, of course, an even darker possibility. What if an anonymous psychopath—Lord knows the internet teems with them—on Discord simply spotted Westman as prey? A confused, deeply sick young man, on mind-altering cross-sex hormones, already drawn to disturbing content. What if this sadistic figure simply wanted to see what would happen, hammering O9A nihilism into Westman’s mind as an experiment, a cruel observation?

Through Westman’s manifesto, YouTube videos, and online statements, we confront the terrifying scope of ideological brainwashing inflicted on young people. Westman may be the first mass murderer to exist entirely at the mercy of such a relentless, self-curated mythology of violence—as if he “rehearsed” by assembling a personal canon of brutality, building toward a climactic, nightmarish performance.

Five days after the Twin Towers were brought down by 767s, 20th-century avant-garde composer Karlheinz Stockhausen made a remark about the 9/11 attacks that few in the West were ready to hear. At a press conference in Hamburg, Germany, he called the attacks “the greatest work of art imaginable for the whole cosmos,” elaborating that the perpetrators had achieved in a single act what composers could only dream of: people rehearsing “like mad for 10 years, preparing fanatically for a concert, and then dying,” culminating in “5,000 people dispatched to the afterlife, in a single moment.”

“By comparison,” he added, “We, the composers, are nothing.”

Stockhausen highlighted the 9/11 hijackers’ decade-long obsessive preparation as akin to musicians rehearsing “like mad” for a onetime performance. In his framework, acts of this audacity reshape reality, inspiring awe or horror that rivals great art. It is almost as if Stockhausen himself glimpsed reality in a manner akin to O9A, in shifting aeonic phases. Though he offered no moral endorsement, he merely observed that earth-shattering acts of mass murder—perpetrated by minds tangled in delirious obsessions with geopolitical ramifications—inevitably usher in new worlds: harsher, uglier, more chaotic versions of the one we currently inhabit.

No doubt, people recoiled at his words, still haunted by the image of innocents plummeting from the sky. But Stockhausen did not mean to glorify the terrorist act; instead, he mirrored Heidegger’s insight from The Origin of the Work of Art: True art does not merely depict reality; it births entirely new worlds. Powerful images, he argued, unleash such overwhelming tragedy that a moment in history is not just marked but also ripped open, a hinge swinging between eras.

In the same terrifying register, the Minneapolis shooting, and the vision of devout children stolen from life, could be seen as a grimly ritualized eruption, a Luciferian anarchy that tears the veil of the ordinary and forces the world to glimpse a fractured, reshaped reality. O9A is a sick ideology, but it does contain a real truth: Shocking and sickening instances of mediatized violence do, in fact, form fault lines between old ways of being and the often terrible new.

The tragedy is that Westman did, in a sense, reshape reality, and we now dwell in a new aeonic phase: an unstable, trembling world forged in the aftermath of his heinous crime.