A Trotskyist’s Road to Teshuvah

“Spy Shcharansky is guilty as hell!”

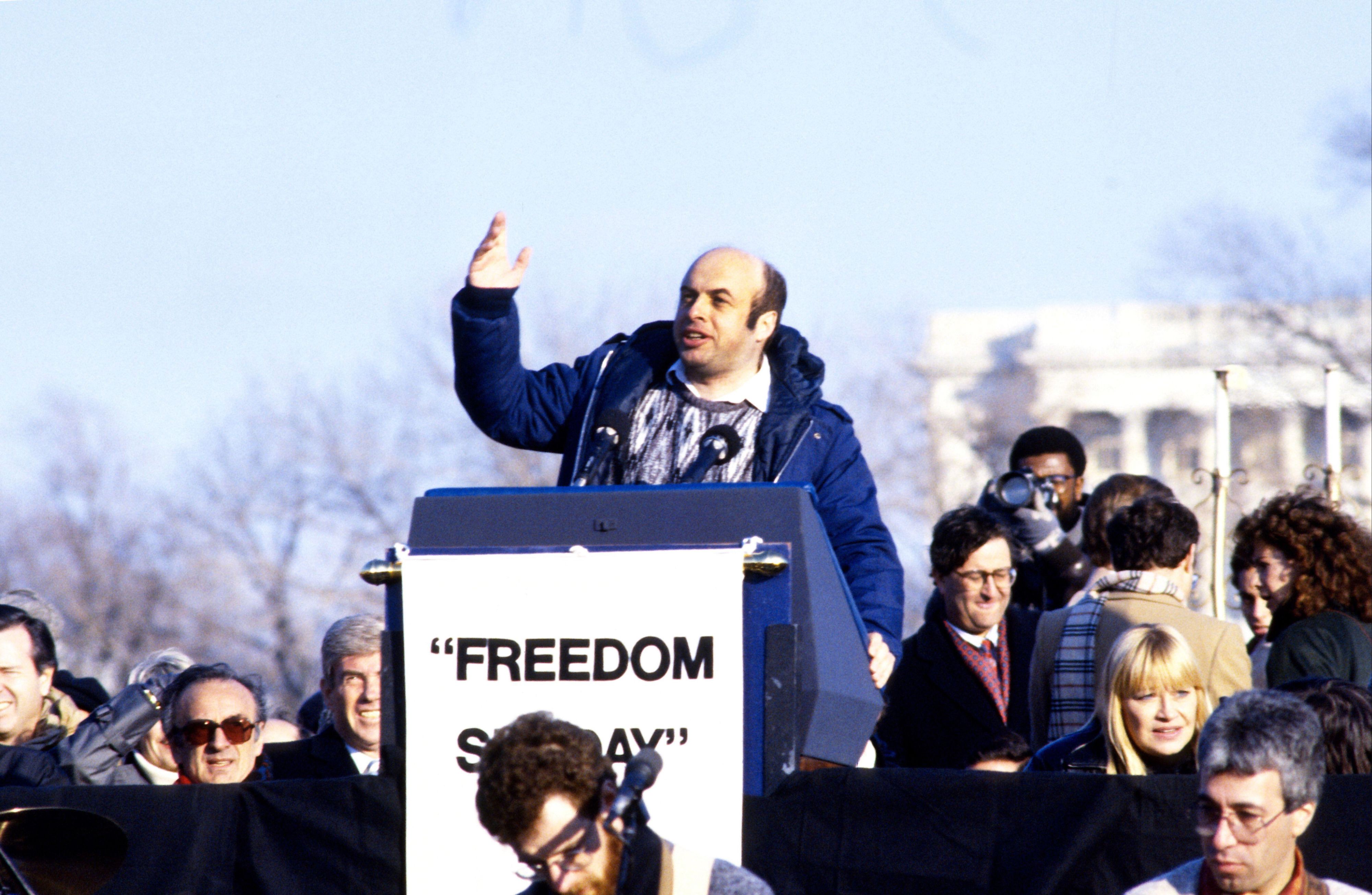

The comrades take up signs and begin chanting, marching in a small circle as I watch a cable car creep up California Street. I’ve come on their invitation to the Fairmont Hotel in San Francisco, where, they’ve told me, an anti-Communist, Reagan-supported “dissident”—you can hear the sneering quote marks—named Anatoly Shcharansky is speaking. He’s been recently released from Soviet prison, where he was justly imprisoned for passing state secrets to the West. Soon he will be known by the name Natan Sharansky, but on this day in January 1987, comrades are forced to grapple with the awkward Russian letter Щ, “shch.” They may hate him, but they’re determined to pronounce his name correctly. It’s “shch,” as in “fresh cheese” or “Khrushchev.”

I am 19 and a sophomore at Berkeley. I’m the product of loving parents and a nice home in Dana Point, a sun-kissed enclave with a charming harbor on the coast of Orange County. I tell the comrades half-jokingly that Orange County’s best chance at salvation will come at the behest of a Red Army invasion. My birthplace epitomizes racist reaction, mindless conformity, and consumerism. Comrades tell me not to be moralistic, that Marxism reveals scientifically how profit comes from exploitation, and imperialism from capitalism. I’ve read Marxist classics that explain these points, but my understanding of economics will always be shaky. What’s important is what feels right: that if people around the world are poor and oppressed, other people must be responsible for oppressing them. I was raised to be one of those people, but now I have a chance at redemption.

I edge into the picket line protest in little increments—first agreeing to carry a sign, then marching in that tiny circle, and finally mumbling the party’s barely comprehensible chants. I am especially impressed by one comrade, a witty, curly-haired Jew named Martha who once lived on a kibbutz. She gives the speech that day, a fiery denunciation of the Anti-Defamation League, the hypocritical imperialist campaign to free Soviet Jewry, and the nuclear-armed madmen ruling Israel. When she tells me that I’d showed grit by coming to the protest, I melt.

Sharansky listens, curious and funny and, I believe, much too forgiving.

I joined the party’s youth organization a few weeks later. Unfortunately for my teenage revolutionary dreams, the Soviet Union soon went into terminal decline. The party threw everything it had—a minuscule but passionate number—into trying to change history. The battle to save the vestiges of the October Revolution seemed to be the final conflict we sang about in “The Internationale,” the apocalyptic showdown between progress and reaction, happening in our lifetimes. Martha went to Moscow to fight the capitalist counterrevolution and was murdered there. Inspired by her courage, I redoubled my commitment to the party, staying for 25 years.

Our internal life was often brutal; the never-ending histrionic Fights to Save the Party were draining and bewildering; we were acutely aware that the outside world found us ridiculous. I doubt anyone really believed in the future triumph of socialism. But quitting seemed impossible. We had a way of describing life outside the party: “leading a biological existence.” It seemed worse than death.

I finally quit in 2016 because I had no idea what I truly believed and was exhausted from pretending I did. Quitting was the hardest thing I’ve ever done. It required taking a scalpel to the core of my existence and led, inevitably, to the loss of my entire social network, career (such as it was), and marriage. But after the initial shock, I experienced the delight of taboo books and thinkers. After so many years of not knowing what I believed, but being afraid to acknowledge it, I could finally mull a thing over and say, I believe this is true.

The most shattering revelation I experienced involved antisemitism. Since my years as a Berkeley radical, I’d considered myself an anti-Zionist. In a remote part of my mind, I also recognized myself as Jewish; I had my mother’s relatives, murdered in Auschwitz, to prove it. But the only point in mentioning my Jewish heritage was to establish that I couldn’t be antisemitic.

In the party, I learned to see Jews as on the wrong side of history, even as we proclaimed our fervent opposition to antisemitism. I still remember a placard carried the day of the Sharansky protest—“20 Million Soviet Citizens Died Smashing Third Reich!”—advertising that the party represented the Nazis’ staunchest, much-suffering enemy and was therefore steeped in virtue.

Read More By Natan Sharansky

Upon leaving the party and questioning my beliefs, I realized just how deeply our worldview was shot through with antisemitism—and the extreme degree to which anti-Zionism like the party’s is antisemitism. From there, I found it easy to see the total legitimacy of, and need for, Israel.

I’d hoped to find a new home on the left consistent with my newfound principles, but the left seemed to have gone spectacularly insane. The sheer craziness of its politics, and its methods of enforcement, in which people were ordered to lie about the obvious realities we saw, reminded me of the very same radical politics I now disavowed.

And, in what would have been a staggering shock to my youthful system, no one captured the Orwellian nature of the woke left better than Natan Sharansky—the very man I’d marched against with my comrades decades ago. Reading his writing about doublethink, I was struck by his observation that today’s left reminds him of the totalitarian state he’d fled from—a state I’d spent much of my life believing was my revolutionary duty to defend. I had no idea if he’d even noticed us crackpot American Trotskyists who picketed him in 1987, never mind given us a thought, but I longed to tell him how sorry I am.

So I write to Natan Sharansky. I send the letter before embarking on my long-overdue first visit to Israel, and to my undying gratitude, a friend of a friend arranges for us to meet. More than 35 years after that protest in San Francisco, on June 25, 2024, at a convivial Jerusalem restaurant with French chansons burbling in the background, I sit face-to-face with him, and I apologize.

He gives no sign of remembering our tiny demonstration but listens with obvious astonishment as I tell him about it and say I’m sorry.

“They told me you were an anti-Communist traitor to the Soviet workers’ state,” I say. Sharansky smiles.

“I was,” he replies.

He peppers me with questions about Trotskyism, and I try to convey how annihilating we’d found the collapse of Communism. One comrade committed suicide. We spent the ‘90s absorbed in anguished retrospection, which ended only when the Second Intifada and the War on Terror gave us new forces to cheer. Since Oct. 7, I’ve watched from afar, sickened, as people I once loved display levels of depravity I wouldn’t have imagined. Sharansky listens, curious and funny and, I believe, much too forgiving. He tells me about Trotsky’s great-grandson who became a settler near Hebron, then talks to me and my two friends about the Gaza war, the slanders lobbed against Israel, wokeism, whether the Democrats or Republicans will win the upcoming election. When he walks out the door, I wonder with pain if I’ll ever see him again, but can’t believe my incredible luck at being granted this chance at teshuvah.

That conversation, and the rest of my visit to Israel, cast a new light on my life. When I thought of my past, including my time on that picket line, I remembered my dawning sense that the comrades and I were not just people, but descendants of patriarchs and prophets of a messianic future. I might have found a sense of belonging and purpose in another group—a conventional career, a family, a cherished circle of friends—but the sense of transcendence and meaning I discovered in the party could only have been found otherwise in religion.

I realized that abandoning the party had left a God-shaped hole in my life, so I figured it was time to give the real thing a try. I’ve started exploring the Judaism my mother’s family abandoned when they fled the Nazi-occupied Netherlands for America. I’ve observed the major holidays, fasted at Yom Kippur, attend a lovely Shabbat dinner weekly at a rabbi’s home. I’ve lit Chanukah candles and have for two years begun the Torah cycle determined to read it weekly, only to give it up around Leviticus. There is a mezuzah outside my door, though I can’t bring myself to touch or kiss it. I remain conflicted about religion as a belief system centered on God. What drives me toward Judaism is my conviction that without it, I am lost, as is our society. I’ve seen in my own life how overthrowing God has brought the West not greater liberation, rationality, and progress, but increasing authoritarianism, irrationality, and barbarism.

In Israel, a country I’d marched against all those stupid years, I found the most remarkable, life-loving, unassumingly heroic people I have ever met. I could see that Israel’s beauty and strength come from its being the Jewish state; the often-rancorous but underlying cohesion of its people is because there’s an ancient moral code that people (mostly) believe in, that give life meaning. When I returned to the United States, I felt the loss of this sense like a missing limb. And I realized I had to work harder to gain some of it for myself.

At one of those weekly Shabbat dinners, one of the guests, a rabbi, remarked that belief in God might be something a person has to work at, the way some people struggle in math. Belief comes easily to him, but for a nonbeliever, gaining a sense of divine presence may be arduous, and ritual observance may sometimes feel pointless. Nothing forces them to try, except that howling emptiness. I’m pretty sure my family thinks my newfound Jewishness is preferable to those years as a Trotskyist, but they must wonder why I can’t just be normal. Even those closest to me may never understand. For now, it’s enough to simply do, and see where the road leads. So when I cast my eyes east these days, it’s toward Jerusalem, in my ongoing, but now very different, quest for redemption.