Media in 2025: The Year Authority Became Performance

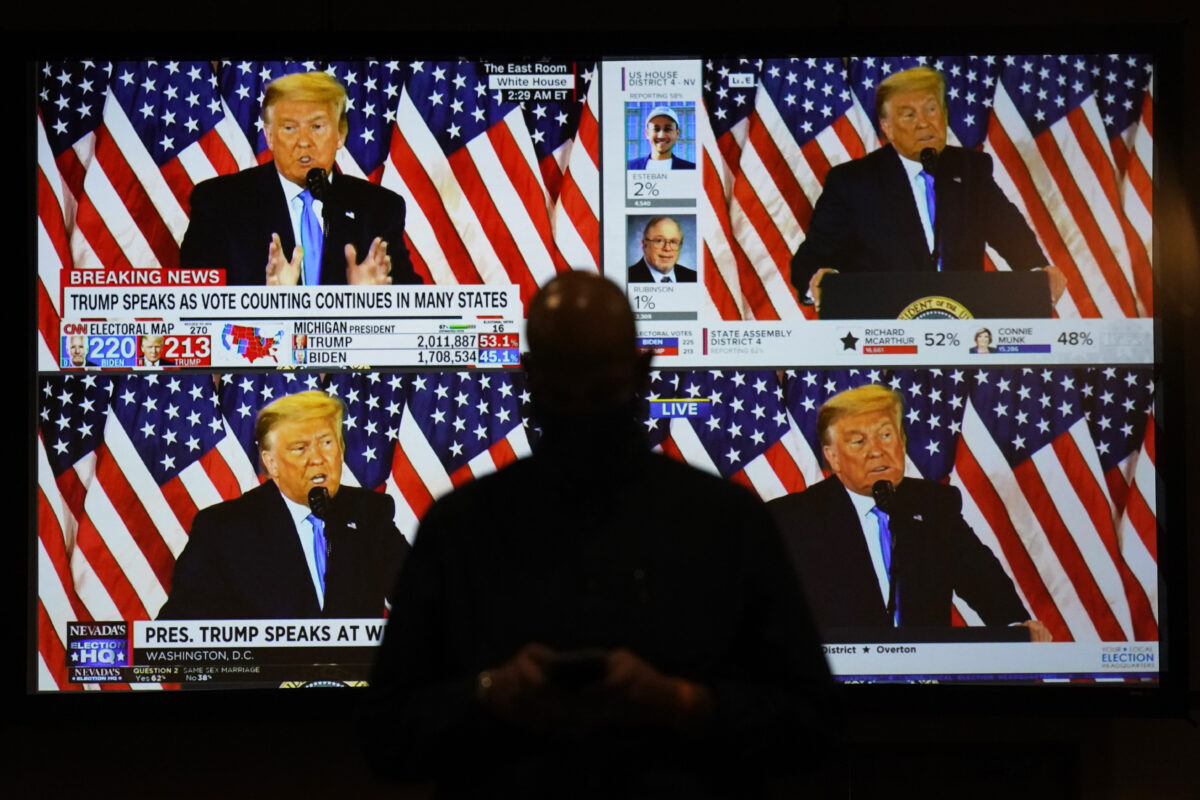

(AP Photo/John Locher)

Every year invites a moment of reflection. In 2025, the media found itself staring into one.

Anyone taking the measure of the media this year had no shortage of weird new images staring back. Hasan Piker, streaming outsider political commentary from his home studio, has built an audience that can rival CNN in prime time. Tucker Carlson, fully untethered from Fox News, built a direct-to-audience outragetainment unconstrained by editors, standards departments, or advertisers. On the left, MeidasTouch became a digital juggernaut by mastering the same mechanics of speed, certainty, and emotional reinforcement.

In 2025, none of this felt shocking anymore, which was the tell. A decade ago, developments like these would have institutional soul-searching, hand-wringing panel discussions and calls for congressional hearings. In 2025, they barely registered, not because the changes were subtle, but because we had grown used to the image. The mirror had been there for years.

The clearest way to understand media in 2025 is simple. Journalistic authority ceased to be something earned through credibility and process and instead became something reflected through performance. What mattered most was not how the image was made, but how it looked when it reached our smartphones.

This represents a massive shift. For most of the modern media era, authority came with friction, and that friction mattered. Editors slowed down stories and required reporters to defend their work. Lawyers asked annoying questions that often made coverage less exciting and more accurate. Institutions absorbed liability and accumulated memory, which meant today’s reporting had to live with yesterday’s mistakes.

Journalism mattered not because it was flawless, but because those guardrails made it more reliable over time, and with that reliability came respect, influence, and a sense of gravitas that extended beyond any single story. That system didn’t disappear overnight, but by 2025, it was no longer in control of how the media actually worked.

The economic pressures that had been building for years finally overtook the cultural norms that once restrained them. Creators no longer operated in the shadow of legacy institutions so much as alongside them, or entirely apart from them, becoming institutions unto themselves—each with its own mirror pointed at its own audience. The promise was democratization. Technology would disintermediate legacy gatekeepers, let more voices reach audiences directly, and make media more responsive to what people actually wanted to hear. That part worked.

What the optimists missed was that removing editorial friction also removed the filtering systems that kept conspiratorial sludge out of the information reservoir. What drives it isn’t ideology, but platform machine learning—more precisely, the angle of the mirror.

The algorithms that replaced editors don’t distinguish between journalism and performance, between verified reporting and toxic speculation, between truth and attention. They reward whatever sparks reaction, letting emotion outrun information and certainty push aside explanation. What spreads fastest often ignores every standard the profession once held.

In that environment, affirmation moves faster than curiosity, and what rises is whatever keeps us looking, not whatever helps us understand. Recommendation systems favor what holds attention longest, creating a feedback loop in which outrage sharpens, identity hardens, and confidence turns into performance. The result is a political media environment designed to make audiences feel morally vindicated rather than better informed. Curiosity now reads as weakness. Pausing to think sounds like hedging. Saying “I’m not sure yet” feels disqualifying, an awkward development for a profession built on not knowing yet.

Once authority becomes tied to audience satisfaction, there’s minimal commercial upside to a fundamental tenet of the fourth estate: speaking truth to power. The media starts to function less as a check and more as a mirror, reflecting the viewer’s appetite back at itself. Social media rewards consumption of comfort food over anything nutritious, and over time, the reflection shows the cost. We’ve gorged ourselves on affirmation and outrage, and the mirror reveals exactly what that diet produces—and it’s not an attractive image — we’ve let ourselves go.

Legacy institutions learned this lesson the hard way. In 2025, major news organizations discovered how little protection authority alone still provides. Disney’s ABC News paid a substantial settlement to resolve President Donald Trump’s defamation lawsuit over on-air statements. CBS, owned by Paramount, faced sustained political and legal pressure amid Trump’s attacks and regulatory threats. Executives weighed business exposure alongside journalistic principle, ultimately settling a remarkably spurious lawsuit over a 60 Minutes edit.

These decisions reflected a new reality in which truth and reputation no longer provided much protection. Even careful journalistic process stopped serving as a reliable shield, and principles became something institutions weighed against cost. Lawsuits and settlements turned into routine business decisions.

The Executive branch recognized what these episodes revealed: abject censorship proved unnecessary because commercial pressure worked just as well. FCC signaling, ownership scrutiny, and regulatory threats landed precisely because they targeted an industry either unsure of its footing or prioritizing the bottom line. Media independence once relied on shared norms as much as legal protections, but when the reflection became negotiable, the norms proved alarmingly easy to discard.

Despite all this, 2025 also produced clear demonstrations of journalistic authority when it was allowed to function at all.

The strongest political journalism of the year focused on how power is exercised, contested, and concealed. Reuters’ Politics of Menace series exposed intimidation ecosystems shaping modern campaigns, documenting threats and coercion as tools of political control. ProPublica and The Texas Tribune traced state and federal efforts to consolidate authority through bureaucratic systems, showing how power moves through rules, appointments, and process rather than speeches.

The New Yorker’s collaboration with ProPublica examined how ideological actors seek to remold the federal government itself, grounding abstract ambition in human decision-making. Politico’s reporting on politically driven pandemic-era investigations showed legal institutions bending under partisan strain, while ProPublica documented direct attempts by political figures to interfere with the press itself.

Jeffrey Goldberg’s handling of what became known as Signalgate belongs in this group. The reporting mattered, but his restraint mattered more. Goldberg treated the material with gravity, prioritizing public interest and national responsibility over theatrics or personal positioning. In a year when certainty functioned as currency, judgment stood out as authority. The mirror did not flatter. It clarified.

Together, this work demonstrated a fundamental truth: Authority still exists when journalism shows its work, accepts risk, and refuses to confuse speed with importance.

Those moments felt radical in 2025, not because they were new, but because they resisted the commercial logic governing so much of the media environment. These outlets were not seeking the blessing of the Trump FCC for a merger or a license, and that independence allowed them to do their jobs. They reminded audiences what authority looks like when it functions: slow, documented, and willing to say less rather than more—a different kind of reflection altogether.

The year forced an uneasy realization into the open, one no algorithm is designed to help us avoid. Authority can be rebuilt through process, or it no longer matters. Audiences either accept responsibility for what rises to the surface, or criticism of the media becomes a way to blame the mirror for what it reveals.

Here is the part people resist. Authority collapsed not only because institutions failed, but also because audiences chose affirmation over information. That preference developed inside platforms designed to maximize attention. It was monetized by creators and companies struggling to survive within that system. Algorithms refined it by learning exactly what keeps people hooked. The reflection did not invent the appetite. It learned to serve it. We’ve grown to hate the media largely because we don’t like what it reveals about ourselves.

What makes this moment particularly unsettling is that we’re living through a transformation with no historical precedent and no clear resolution. The technology moved faster than our ability to adapt to it, and we’re now adjusting to this information ecosystem in real time, with no roadmap and diminishing faith in the institutions that might have guided us through it. It’s likely to get worse before it gets better, if it gets better at all. We’re building the plane while flying it, except the plane is also the air traffic control system, and no one is entirely sure who’s piloting.

Journalistic authority did not vanish. It was replaced by something faster, louder, and far worse at saying the four words journalism once relied on most:

I don’t know yet.

This is an opinion piece. The views expressed in this article are those of just the author.