Weaponizing "Misinformation" to Bury Safety Concerns: A Response on RSV Monoclonal Antibodies

Published by permission of the Author

I am admonished that I need to add a specific disclaimer that the following does not represent the position of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, the US Center for Disease Control or Prevention, or the US Government.

This essay relates to the following previously published Substack essay by the same author, and represents a response to critics of the prior:

What The ACIP Wasn’t Shown

Introduction by: Dr. Robert Malone…

6 days ago · 333 likes · 114 comments · Robert W Malone MD, MS

Yaffa Shir-Raz

The recent critique raises a number of claims regarding my article. This response addresses the substantive points directly, focusing solely on the evidence.

When evaluating new interventions for healthy newborns, presenting the full safety record – including every death – is not optional, it is a fundamental obligation. This is always true, but in the case of Merck’s clesrovimab it was especially critical: the FDA skipped presenting the product to its advisory committee on the grounds that it was "not first in class." This left ACIP as the only public forum charged with reviewing the product. Instead of two independent layers of oversight, there was only one. In such circumstances, withholding or downplaying deaths meant that ACIP – the sole safeguard – was not given the complete picture it needed to protect infants and families.

Before turning to the substantive issues, two clarifications are in order:

A large portion of the critique is devoted to personal ad hominem remarks. Such rhetoric does not honor the principles of scientific debate and is contrary to what science should represent. I will therefore not address these attacks further.

Some of the first claims in the critique actually concern an article by Dr. Maryanne Demasi, which I cited. Since I included them, I will clarify them briefly:

"The CDC split the age groups (0-37 days vs. 38 days-8 months) for sound epidemiological reasons, not to conceal a signal."

My article highlighted that the split erased statistical significance. A unified calculation shows a nearly four-fold increase in seizure risk, a signal that was never presented to ACIP. The split was not explained during the meeting, and it occurred exactly at the point when routine vaccinations begin. Even if additional vaccines are a confounder, that does not absolve the CDC of its obligation to present the combined analysis. An advisory committee deserves to see both the stratified and the pooled results.

"Pooling the two age groups is not epidemiologically valid."

I wrote explicitly that the problem lies in presenting only a single stratified analysis that removed the signal. Good pharmacovigilance practice requires sensitivity analyses, including pooled windows and alternative models. A pooled analysis is standard in post-marketing surveillance, and the CDC should have shown it as well.

Beyond the factual dispute, this argument demonstrates a methodological fallacy: it invokes epidemiological rigor selectively. The critic dismisses pooled safety analysis as "inappropriate" while ignoring that pooling is exactly the standard practice for rare adverse events. This selective deployment of rigor is itself unscientific. The same inconsistency appears in the treatment of confidence intervals: wide intervals do not make results meaningless; they mean large risks cannot be ruled out, which is precisely why transparency is required.

With respect to my own critique, the relevant claims are as follows:

Claim 1: "Clesrovimab and nirsevimab are fundamentally different, not ‘nearly identical.’ "

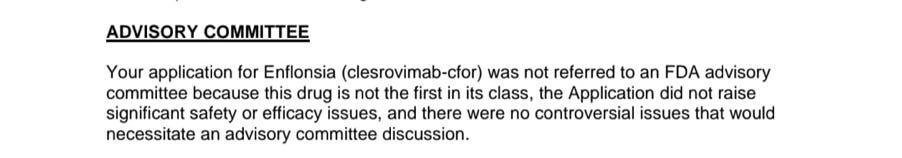

The critic claims that Merck’s clesrovimab is "fundamentally different" from Sanofi’s nirsevimab, and therefore safety findings from one cannot be extrapolated to the other. Yet the FDA itself contradicts this assertion: in its official approval documents, the agency explicitly noted that clesrovimab was "not referred to an FDA advisory committee because this drug is not the first in its class." In other words, the FDA regarded clesrovimab as part of the same extended half-life monoclonal antibody class as nirsevimab, and therefore waived a separate advisory committee review.

If the products were truly "fundamentally different," logic dictates that the FDA would have convened an independent review of clesrovimab’s safety and efficacy. The fact that it did not do so proves the opposite: from a regulatory standpoint, the two products are treated as virtually identical. Regulators cannot have it both ways – claiming fundamental difference to deflect criticism while justifying the absence of oversight on the basis of sameness.

Claim 2: "Deaths were not hidden; they were reviewed and deemed unrelated. Regulators are transparent."

This is misleading. FDA reviewers themselves described the mortality imbalance as "unexpected" and "surprising." The issue is not whether a reviewer wrote "not related, " but whether ACIP and the public were shown the full picture.

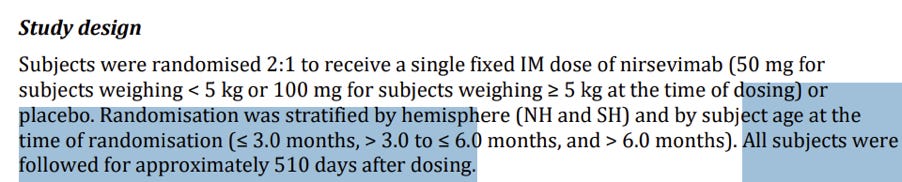

In the MELODY trial (nirsevimab):

Day 440 falls within the overall protocol-defined follow-up window of 511 days.

The study's protocol explicitly notes (p. 5): "The final analysis for safety follow-up will be conducted when all subjects have completed the last visit of the study (ie, Day 511)." Classifying it as "out of window" applies only to the narrower 360-day statistical analysis frame, not to the official follow-up duration. In any discussion of overall mortality balance – and especially in the context of transparency to an advisory committee – there is an obligation to present all events that occurred between Days 361 and 511, rather than restricting the picture to the first 360 days alone.

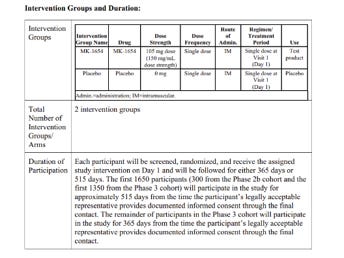

In the CLEVER trial (clesrovimab):

The protocol specified that some participants were followed for 365 days, others for 515 days. A death on Day 487 was reported (slide 11) only as: "One death occurred in the clesrovimab group on Day 487 after study discontinuation (discontinued study based on physician’s recommendation). " Beyond that half-sentence, no information was provided. Why did the physician discontinue participation – was it due to a serious adverse event? What was the infant’s condition between discontinuation and death? Was this an additional, eighth death, or one of the seven already counted? Even this basic point is unclear.

But the problem is not confined to these two footnote cases. A recurring pattern is visible across both products: for example, deaths attributed to SIDS, or two deaths from gastroenteritis in the Nirsevimab MELODY trial – a vanishingly rare cause of death in healthy infants in high-income countries. Without detailed timelines or case circumstances, it is impossible to judge whether these were indeed random coincidences, as claimed, or whether they reflect a safety signal.

International standards (ICH E3, section 12.3.2) require full narratives for every death and other serious adverse events. These narratives must detail the clinical course, exact timing, lab results, treatments, and both investigator’s and sponsor’s causality assessments. This requirement is not technical – it is essential to enable advisory committees, independent regulators, and the public to determine whether unexpected deaths form a pattern. A half-sentence or a footnote table does not meet that standard.

Moreover, a complete and transparent briefing to ACIP should have included not only raw death counts by trial arm but also a structured table listing cause of death, timing, and arm assignment for every case. That level of detail is essential according to multiple methodological and regulatory standards. The CONSORT Harms 2022 extension stresses complete, prespecified reporting of harms in randomized trials. The ICH E9(R1) guideline underscores defining estimands clearly and providing transparent analyses that allow independent scrutiny. Together, these standards make clear that selective omission or minimal tabulation of deaths falls short of internationally accepted requirements.

Furthermore: while the FDA did publish an integrated review for nirsevimab, it did not provide full narratives or timelines for every death. For clesrovimab, the situation is even worse: the product was never brought before an FDA advisory committee, having been classified as "not first in its class. " In other words, no transparent public review of safety data took place – precisely in a program where trial arms showed excess deaths compared to controls. Without such public review and without full disclosure of data to ACIP, neither experts nor the public can accurately assess the risk–benefit balance.

If the critic does possess additional data, especially regarding the two footnoted deaths, then withholding them from ACIP and the public would itself constitute a breach of transparency.

Even beyond these transparency failures, the reasoning offered to downplay the reported deaths rests on methodological fallacies. To dismiss trial deaths because they arose from "varied causes" (SIDS, gastroenteritis, malnutrition) ignores the core principle of pharmacovigilance: patterns can emerge without a single neat mechanism. Consistency, timing, and imbalance across trial arms are sufficient to warrant further scrutiny. History offers clear precedent, as with tobacco and lung cancer, where causality was recognized long before a precise mechanism was known.

Likewise, reliance on FDA reviewers’ individual "not related" judgments illustrates an appeal-to-authority fallacy. Individual case reviews operate at the level of counterfactuals for single patients, while mortality imbalance is a population-level signal. Confusing these levels is a categorical error that obscures the real question: whether trial arms differed systematically in death rates.

Claim 4: "You ignore real-world data showing 30-50% reductions in hospitalizations and 80% effectiveness in Canada."

First, when evaluating "real-world effectiveness," the critical endpoint is mortality. Hospitalizations may decline, but what ultimately matters is whether the intervention saves lives or, conversely, introduces new risks of death. The FDA itself acknowledged “an unexpected imbalance” in mortality within the pivotal trials. This must be assessed against the real-world baseline: in high-income countries, RSV-related infant deaths are already exceedingly rare. In the US, a nationwide study of over 80 million live births (1999-2018) documented an average of only 28 infant deaths per year due to RSV (6.9 per 1,000,000 live births). When the disease causes so few deaths in healthy term infants, even a small numerical excess of deaths in trial arms raises a red flag. The risk–benefit analysis cannot ignore that preventing hospitalizations in large numbers of infants is meaningless if the preventive product itself carries a mortality signal that may outweigh the disease’s own lethality. Transparency therefore requires full disclosure of case narratives, timing, and stratification, in line with ICH E3 standards.

As for the "real-world effectiveness" studies cited by the critic: the CDC’s MMWR report is an ecological analysis with major limitations – no individual-level coverage data, abnormal post-COVID seasonality, regional variation in product availability (e.g., Houston), possible under-ascertainment, and interim results only through February 2025. As the report itself states: "Coverage data … are not yet available at the individual level … post–COVID-19 circulation patterns might complicate comparisons … and these are interim results, limited to data available through February 2025. " In other words, even the CDC cautions that these declines in hospitalizations cannot be interpreted as definitive evidence of real-world effectiveness, and certainly not as a substitute for transparent mortality data.

The supposed Canadian figure of "80% effectiveness" is on even weaker footing. Here the critic is not citing a scientific publication at all, but a popular media article from the Canadian Press, which in turn referred vaguely to "preliminary results of a study" without providing any link or accessible report. In other words, the critic dismissed our reliance on regulatory documents and trial protocols while relying on journalistic reporting without scientific verification. Such media-based claims cannot substitute for transparent, peer-reviewed safety and efficacy data.

This is a textbook case of selective rigor: demanding the highest evidentiary bar for safety signals while accepting the lowest standard for positive efficacy claims. Such asymmetry erodes scientific integrity.

Taken together, the critique reflects systematic reasoning failures. It dismisses pooled safety analyses as "inappropriate" while uncritically embracing weak observational reports, a selective rigor that distorts scientific balance. It treats FDA reviewer notes as proof of safety, despite the agency itself acknowledging a "surprising mortality imbalance" and never convening an advisory committee for clesrovimab. It misrepresents statistics by calling wide confidence intervals "meaningless," when in fact they highlight uncertainty and the possibility of clinically significant harm. It portrays varied causes of death as evidence against a safety signal, ignoring that pharmacovigilance often detects patterns across diverse outcomes. And perhaps most concerning, it weaponizes the label of "misinformation" to delegitimize methodological critique rather than addressing it with data.

In sum, this is not about individuals or personal debates, but about protecting infants. When a mortality imbalance emerges in trials of products intended for healthy newborns, transparency must be paramount. Advisory committees and the public deserve full disclosure of the data – narratives, timelines, and analyses – not selective or misleading presentations that obscure critical safety signals. Withholding critical information and misleading the ACIP undermine the advisory process itself and strip the public of the assurance that infant safety is being rigorously protected.

Thanks for reading Malone News! This post is public so feel free to share it.