Mexico Has No Right to U.S. Territory

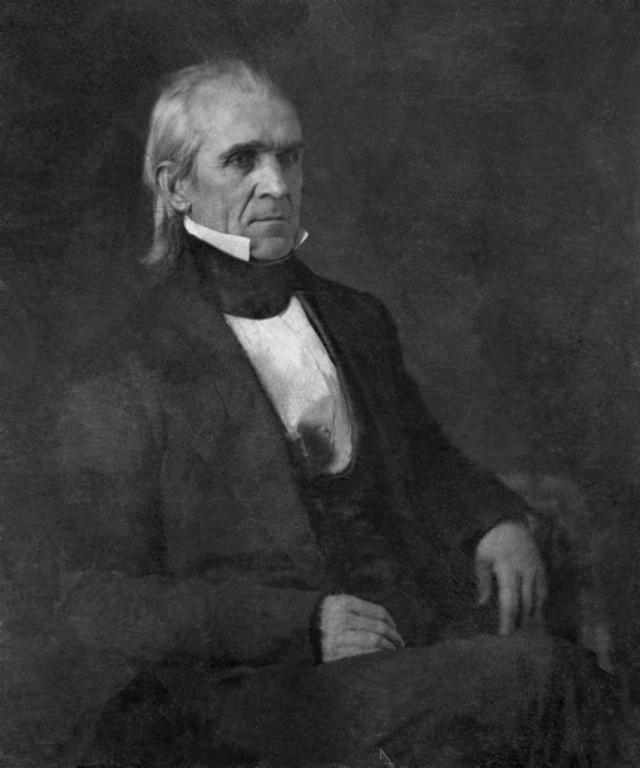

James K. Polk was our most underrated president. A protégé of Andrew Jackson, Polk, a Democrat, won an improbable victory when he beat the Whig candidate Henry Clay in the 1844 presidential election. During his single, tumultuous term, he expanded U.S. territory across vast expanses of the West and Southwest, from the Rio Grande to the Pacific Coast up to the 49th parallel. He lowered the heavy tariffs supported by the industrial north, stripped public tax funds from unaccountable private banks and created an independent Treasury that survived for more than 60 years. By the time he left office in March 1849, he was played out physically and politically. He would be dead within four months, at the age of 53.

Robert W. Merry wrote a masterful biography of James Polk titled A Country of Vast Designs, wherein he lays out the nuanced and complex history of this era. For example:

Mexico established its independence from Spain in 1821 and set about to address a problem that had plagued the Spanish overlords for generations -- the dearth of settlement in Texas and California and a consequent inability to establish dominion over those lands. Unlike the robust Anglo-Saxon migrations to the New World, the Spanish influx had not encompassed large numbers of families seeking land for cultivation and settlement. The Spanish migrants had been more bent on establishing themselves as a societal elite superimposed over the established Indian societies. This worked in the New Spain heartland, where the populous Indians had established a high degree of civilization. But in areas such as Texas, where the landscape was forbidding and Apache and Comanche Indians posed a brutal threat, it faltered. To address this problem, Spain had granted large tracts of Texas land to an American group headed by Moses Austin.

In 1821 Austin’s son Stephen began selling land to American settlers “willing to brave the hardship and Indian attack.” By 1835 they numbered almost 40,000, and ten years later almost 150,000. In 1830, Mexico tried but failed to outlaw this wave of immigration. Inevitably, the Texas migrants, rejecting fealty to Mexico, declared their independence in March 1836 and “repulsed efforts by Mexican president Antonio López de Santa Anna to bring them to heel.”

Mexico never accepted Texas’ independence. For most of the next decade, an official state of war existed between Mexico and Texas, but with no actual fighting. Meanwhile, Britain was trying to establish a political and military alliance with financially strapped Texas in order to undermine U.S. supremacy over the Gulf of Mexico, including New Orleans and the Mississippi delta. (Britain and the U.S. had both occupied the Oregon Territory since an 1818 treaty. With masterful diplomacy amidst political infighting, Polk managed to wrest that territory away from Britain without firing a shot with the Oregon Treaty of 1846.)

Mexico never accepted Texas’ independence. For most of the next decade, an official state of war existed between Mexico and Texas, but with no actual fighting. Meanwhile, Britain was trying to establish a political and military alliance with financially strapped Texas in order to undermine U.S. supremacy over the Gulf of Mexico, including New Orleans and the Mississippi delta. (Britain and the U.S. had both occupied the Oregon Territory since an 1818 treaty. With masterful diplomacy amidst political infighting, Polk managed to wrest that territory away from Britain without firing a shot with the Oregon Treaty of 1846.)

If the U.S. acquired Texas, not just to keep Britain at bay, but to pursue the sea to shining sea ambitions of Manifest Destiny, then the U.S. would also acquire its war with Mexico, which is exactly what happened. Long story short, a two-year war ensued and effectively ended when U.S. forces captured Mexico City in September, 1847. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo formally concluded hostilities in February, 1848. By the terms of that treaty, Mexico ceded Texas, plus all the territory currently comprising Utah, Nevada, California, most of New Mexico and Arizona, and parts of Oklahoma, Colorado, and Wyoming. Although Mexico lost almost half of its territory, that accounted for only about 1% of the country’s population. The U.S. paid Mexico $15 million and assumed $3.25 million in claims held by U.S. citizens against Mexico. Mexicans who were now living in an expanded United States could return to Mexico or become U.S. citizens, with a guarantee that they would retain their property rights.

Recently Gerardo Fernández Noroña, president of the Mexican Senate, related how he met with President-elect Trump a couple weeks before his inauguration in 2017. Mr. Noroña said “Yes, we’ll build the wall, yes, we’ll pay for it, but we’ll do it according to the map of Mexico from 1830.” He then held up such a map, when Mexico controlled what is now California, Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas and parts of Colorado. Noroña admits that “of course” this land is part of the U.S., but he and many Mexicans and Mexican Americans harbor a seething resentment that we stole that land from them. As Pat Buchanan has said, “demographics is destiny,” and the flying of Mexican flags at anti-ICE demonstrations in California reflects a belief that mass migration from Mexico to the U.S. is how that “destiny” of repatriation can be realized.

In “California Was Never the ‘Homeland’ of Mexican Invaders” Hayden Daniel writes:

In the 1820s, the non-Indian population of Alta California, which included California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, and parts of New Mexico, stood at barely 3,000 people. Similarly, only about 5,000 Mexicans lived in Texas in 1830. For comparison, Mexico as a whole had a population of somewhere between 6 and 8 million people in 1830. A tiny fraction of the total population living in an area does not denote a “homeland” by any stretch of the term.

No country over the past hundred years has flung open its borders as did the Biden administration. An unknowable number of unvetted people entered the U.S., often assisted with U.S. tax money by the UN and NGOs in the Panamanian Darién Gap and southern border towns. Those cynical, destructive border policies created an understandable but misplaced sense of suffered injustice by many of the people who are now being forced to leave, after feeling as though they had been invited in through a giant, mostly open door.

President Trump recently directed DHS to concentrate on deporting criminals, and to stop deporting illegal immigrants working in farms, hotels, and meat packing plants. ICE isn’t storming public schools and rounding up children for deportation, but many who came here illegally must be sent back to their home countries.

Millions of Mexicans have emigrated here over the years, worked hard and assimilated into American culture. But it’s pointless and counterproductive for Mexicans to believe they have a right to reclaim land “stolen” from them by the United States.

Image: Public Domain