Remitly Exposed: How a Bezos-Backed Remittance App Allegedly Launders Terror Cash While Dodging U.S. Law

A major driver of immigration—both legal and illegal—to the U.S. is remittances, or payments sent by immigrants back to their families in their home countries. Remittances are one of the largest industries in the world, with remittances accounting for 3.5 to 4 percent of Mexico’s total GDP and 3.4 percent of India’s. As such, these and other countries will do anything to keep the flow of income from the U.S. coming. With Trump’s FinCEN having recently announced it will go after remittances sent by illegal aliens, I can now reveal that Remitly, one of the largest remittance services in the world and popular among Indians, Mexicans, and Filipinos, is allegedly intentionally maintaining loose oversight over the payments sent via their platform. To make matters worse, there is a significant probability that many of their customers are engaged in money laundering for terrorist groups in Africa and the Middle East. If true, the allegations represent a major violation of state and federal anti-money laundering laws.

Remitly and the Alleged FraudOriginally launched in 2011 as a remittance service search engine named BeamIt Mobile, Seattle-based Remitly has emerged as one of the largest players in the remittance industry. Remitly was backed by several major Big Tech figures including Amazon founder Jeff Bezos and former Google CEO and executive chairman Eric Schmidt. It extensively raised venture capital throughout the 2010s and made an initial public offering in 2021 that raised $300 million in revenue; it is currently traded on the Nasdaq Stock Exchange.

The Visa Files is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

I was recently contacted by an insider with over a decade of experience working for major banks as a risk officer. They also hold an advanced degree in computer science and through their education and experience, they are intimately familiar with the basic automated controls that any financial service must implement in order to comply with U.S. KYC (know your customer) and AML (anti-money laundering) laws. All financial institutions must adhere to these under laws such as the Bank Secrecy Act, and failure to do so can result in crippling fines and even criminal prosecutions. For example, USAA’s failure to properly record its customers’ transactions resulted in the company failing multiple federal audits, forcing it to sell off its real estate, asset management, and investment management divisions. Below is a list of audits that USAA failed:

The insider details how they recently went through an interview at Remitly for a job heading up their KYC/AML privacy controls program. During the interview, they discussed many of the basic automated controls necessary for such a system, including FinCEN (the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network) checks, OCC (Office of the Comptroller of the Currency) anti-terrorist checks, tax evasion name/identity checks, and transaction pattern checks to avoid generating SARs (suspicious activity reports). In the process, they uncovered “willful failure to automate basic controls” on Remitly’s part, failures that Remitly is required to automatically report to both state regulators and the Department of the Treasury. As the insider puts it, after they “rattled off the laundry list of standard automated controls any bank should put into place to avoid liability for terrorist financing,” Remitly abruptly ended the interview process, determining they were a bad “team fit” and refusing to speak to them any more.

If true, this is a major red flag on Remitly’s part. The insider notes that they are unable to go public about this themselves because it would end their career.

Remittance Networks and the Motivation for FraudThe sheer size of the remittance industry—as well as foreign nations’ active interest in keeping remittances flowing—creates a gigantic incentive for remittance services to turn a blind eye to money laundering. As the insider puts it, Remitly benefits from its alleged failure to implement KYC/AMC controls because of the low barrier to entry to the remittance industry: “Anyone with $200,000 in investment funds can set up the necessary computer systems and the correspondent banking relationships around the world to enable transfers and begin processing money movement on behalf of [their] customers.” The insider points out that Remitly and services like it use loose controls as a “hidden selling point” to claw business away from more mainstream competitors such as Western Union, Stripe, Block, and so on, saying that HSBC and Barclays did the same back in 2008 and 2012, respectively.

There is an entire ecosystem of remittance and money transfer services that most Americans do not know about because they are only advertised to foreigners. For example, this is a flyer for remittance service TransFast that I photographed over the summer at a Mexican restaurant in Poughkeepsie, New York:

I saw a Jamaican restaurant on the same street (Main Street) that was advertising a different remittance service. These services are typically marketed to specific immigrant groups as a means of cutting through the red tape involved with traditional money transfers, with faster transfer times and lower fees then banks or wire services like Western Union. It is likely many of them are engaging in the same illegal facilitation of money laundering that Remitly is accused of.

Remittances make up a shocking percentage of economic activity in many poorer countries, which leads them to fight tooth and nail to maintain the flow of income from their citizens in the U.S. This can be seen in how the Mexican government had a meltdown over the remittance tax that was passed into law earlier this year as part of the One Big Beautiful Bill. Mexico has begun issuing debit cards to its citizens as a means of circumventing the tax, which seems like a major KYC/AML violation on its own, on top of the Mexican government facilitating tax evasion. India has similarly protested the OBBB’s remittance tax, though the Indian government has taken no overt actions to counter it, unlike Mexico.

A considerable amount of pro-immigration sentiment in the U.S. is driven by foreign corporations and oligarchs who profit off of remittances, either directly or indirectly. Over the past two decades, Steve Sailer has reported extensively on Carlos Slim, the CEO of Mexican telecommunications companies Telmex and América Móvil, as well as one of the New York Times’ largest shareholders (and at one point, the largest single shareholder). Telmex is a formerly state-run corporation that was privatized and sold to Slim in the 90s and still holds a virtual monopoly over landline telephones and Internet services, while América Móvil—itself spun off from Telmex—holds a near-monopoly on mobile services, including calls between Mexico and the U.S. Both Telmex and América Móvil charge exorbitant fees for their products; in 2006, the average Mexican small business had an average phone bill of $132 per month, compared to $60 per month in the U.S.

This state-backed monopoly has made Slim fabulously wealthy: from 2010 to 2013, he was the richest man in the world, and he is still the richest man in Latin America. As Sailer writes, Slim actively supports mass immigration from Mexico to the U.S. because he heavily profits from remittances which Mexicans back home spend on his companies’ services. When the New York Times was on the verge of collapse in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, Slim loaned the NYT $250 million and later purchased many of the newspaper’s shares, owning over 17 percent of the New York Times Company by 2016. It is clear that Slim did not do this out of charity, but because he sought to use the New York Times to push a pro-immigration agenda for him to profit further, especially since it is widely accepted that Jeff Bezos purchased the Washington Post to advance his own agenda. Slim was also involved in the Mexican government’s fight against the OBBB remittance tax.

The Indian government also has its own network of oligarchs, pressure groups, and unregistered foreign agents who advocate for pro-Indian, pro-mass immigration policy. As Amanda Bartolotta reported last week, an Indian venture capitalist named Asha Jadeja Motwani is claiming credit for reversing Trump’s position on H-1B visas, openly bragging about how she advocates for Indian interests despite not being registered under the Foreign Agents Registration Act, a violation of federal law. If you recall, Maria Butina was arrested and prosecuted in 2018 for allegedly violating that same law.

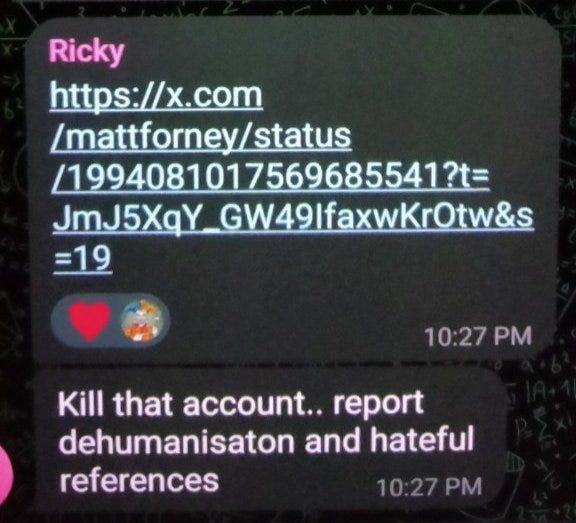

The sheer amount of money at stake for India, Mexico, and other third world countries from remittances alone means they will do anything to keep the Trump administration from turning the spigot off. I’ve posited in the past that the Indian government has positioned spies in the crucial American industries they now dominate, spies who could be ordered to wreak havoc on American national security and the economy should India’s interests be threatened. We have already seen how Indians at X/Twitter have manipulated the platform to silence their critics, allowing mass report groups to ban “enemy” accounts or spam them with bogus Community Notes (which impacts income, since X posts that have Community Notes are demonetized). This is a screencap of an Indian mass reporting Telegram group where they are targeting my X/Twitter account:

The mafia-like behavior that Indians act out on their critics, up to and including hacking, death threats, and physical stalking suggests that India absolutely would carry out greater acts of sabotage against the U.S. should the borders be closed to them. Given that Mexico has already seen remittances plunge to their lowest levels in years, I expect India’s lobbying and harassment to get worse.

Remittances Are Defrauding the American EconomyGiven the grave nature of the allegations against Remitly and the Trump administration’s promised crackdown on cross-border financial transactions, Remitly must be investigated as a matter of national security. Other remittance services should also be looked into and the river of money flowing to other countries dammed through taxation, vigorous IRS and FinCEN enforcement, and mass deportations.

The infrastructure to do this already exists. When I lived in Georgia (the country) years ago and went to open a local bank account, the bank (which has no branches in the U.S.) forced me to fill out an IRS form to confirm I wasn’t trying to evade taxes. Since FATCA (the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act) came into effect in 2010, the IRS has been pressuring and threatening foreign banks into turning over information on their American clients, and banks in traditional banking havens like Switzerland and Hong Kong often now refuse to take American clients because they don’t want the hassle.

Similarly, at the end of last year, American businesses were facing the looming threat of the Beneficial Ownership Information report, a new FinCEN requirement that forced LLCs to file information on their owners with the Department of the Treasury or face fines of up to $10,000 per day. This rule, passed as part of the omnibus budget bill at the end of 2020 and touted as an AML effort, was halted by a federal court and eventually overturned (with the exception of foreign-owned LLCs), but other states such as New York are implementing their own beneficial ownership reporting requirements.

If the IRS can hound banks around the world over their American clients, if FinCEN can impose ridiculous regulatory requirements aimed at bankrupting small businesses, then remittance companies can be audited and shut down if they are not complying with federal law. We can rebuild America. We have the technology.

If you are a whistleblower/have insider information from Remitly or any other remittance service, feel free to reach out to me via Substack DMs, X/Twitter DMs, or email at mattforney [at] protonmail [dot] com. All communications are confidential and your anonymity will be protected.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing by clicking here. Most articles on this blog are free, but your support gives you access to paywalled articles and enables me to do this work. You can also make a one-time donation here (note: this does not give you access to paywalled articles, unfortunately). Follow me on X/Twitter, where I post stories more frequently, here.

The Visa Files is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.