Meet the Lurie-loving crypto bro helping lead Powell Street’s turnaround

Max Raskin is not a name that rings out on Powell Street.

He’s not a tech billionaire, a legacy developer, or a City Hall insider. But the Lurie-loving, Kardashian-curious crypto evangelist has quietly become one of the most influential figures betting on Union Square’s revival.

As San Francisco shakes off its pandemic slump, few streets matter more than Powell. Once a postcard symbol of the city, it became shorthand for downtown’s troubles. Raskin is part of a new crop of out-of-town investors wagering millions that the area’s best days aren’t behind it.

Raskin and Ian Jacobs founded Uris Acquisitions to bet on San Francisco real estate. | Source: Courtesy of Max Raskin

Raskin and Ian Jacobs founded Uris Acquisitions to bet on San Francisco real estate. | Source: Courtesy of Max RaskinColleagues and acquaintances say he’s a charismatic, libertarian-leaning Renaissance man and super networker, with a longtime fascination for cryptocurrency and a more recent ardor for Mayor Daniel Lurie.

“Max is about the most colorful person I know,” said New York University Professor David Yermack, who has taught a course on digital currencies (opens in new tab) alongside Raskin over the past decade. Raskin has used his connections in the crypto world to bring in guest lecturers like the Winklevoss twins.

While both he and Jacobs live outside of California, the Uris team is bullish on San Francisco generally and Union Square specifically, according to Darren Kuiper, a senior VP at real estate brokerage Colliers who has worked with Uris on its building deals.

“They are really huge believers in Mayor Lurie and what he’s doing,” Kuiper said. “They’re also believers in the long-term San Francisco story, which is music to my ears.”

Making friends in City HallSince Uris launched last year, Raskin and Jacobs have become the most prolific real estate investors on Powell Street, purchasing three properties: the green, art deco-building at 200 Powell, which attracted red-hot Chinese toy company Pop Mart as a tenant; 35 Powell St., which overlooks the cable car turnaround and has Burger King as a tenant; and 111 Ellis St., a vacant corner building that previously housed Blondie’s Pizza on its ground floor.

While Uris isn’t the only outside investor aggressively courting Union Square — a Texas group has also bought a handful of properties (opens in new tab) recently — it has staked its claim on the Powell Street corridor.

It’s a strategy aligned with the priorities of Lurie and the Downtown Development Corporation he spun up to turn private dollars into public improvements. A bond measure passed by voters last November is directing more than $20 million toward improving infrastructure on Powell by adding art nouveau-style lighting, widening sidewalks, and replacing parklets with space for outdoor dining, trees, and seating.

A trolley passes 111 Ellis St., one of the buildings that Uris acquired. | Source: Frank Zhou/The Standard

A trolley passes 111 Ellis St., one of the buildings that Uris acquired. | Source: Frank Zhou/The StandardTrue to character, Raskin has cozied up to Lurie in his own way. He interviewed Lurie (opens in new tab)for his blog before the election, asking about the candidate’s denim preferences and love of “The Rock,” the Nicolas Cage movie about breaking into Alcatraz. A few months after Lurie’s inauguration, Raskin followed with a glowing Wall Street Journal op-ed (opens in new tab) about how the mayor had turned San Francisco around in short order with the help of his close ties to the city’s coterie of billionaires.

“My business partner and I saw an opportunity,” Raskin wrote. “We began buying real estate in San Francisco because we believed its problems were man-made and therefore reversible by the right man.”

In May, Uris bought its first Powell Street building. The following month, Raskin arranged a meeting at City Hall with one of the administration’s top deputies, Ned Segal, and investors in Uris, including representatives from MIT’s investment management firm and the family office of Sutter Hill Ventures executive G. Leonard Baker, according to city records. Lurie himself stopped by.

In setting up the briefing, Raskin wrote that he and the team looked forward to telling Lurie “how excited we are about what he’s doing :)”

In mid-November, Segal again met with the Uris team, as well as the director of investments at Boston University, to discuss Union Square’s recovery. “Uris Acquisitions has made early bets on downtown — it’s an encouraging sign of the direction our city is heading,” Segal said in a statement.

Early next year, Raskin will further entrench himself in the city by joining the board of Golden Gate University, according to its president, Brent White, who describes him as “full of energy, ideas, and a little quirky.” The duo met through mutual mentor John Sexton, the former president of NYU, and Raskin will advise the university on its own potential expansion in Union Square.

A super-connector who loves cryptoRaskin’s networking ability is part of why Jacobs tapped him as a founder of Uris: “In addition to being a terrific partner and friend, Max brings with him an incredible ability to build trust and consensus across investors, civic leaders, and communities,” Jacobs said. “It’s a rare skill.”

Despite Jacobs’ family history, both he and Raskin were newcomers to real estate investment. Both went to college in New York City: Raskin at NYU and Jacobs at Columbia. While Jacobs’ early career included a stint as Warren Buffett’s financial assistant (opens in new tab), Raskin began working as a Bloomberg News reporter, covering financial markets and the early days of bitcoin.

“Max was an early believer in crypto,” said University of Chicago professor M. Todd Henderson, who coauthored a paper with Raskin in which they coined the “Bahamas Test,” a hypothetical for determining whether a digital asset should be considered a security. (If the asset would survive its founders decamping to a tropical island, it isn’t a security.)

Yermack described Raskin’s perspectives as aligned more closely with those who think “crypto will overtake and make the financial system obsolete,” than those who think it will just make the current system better. “Max has got a lot of libertarian beliefs that dovetail with the people who created crypto way back when,” the NYU professor said.

Raskin met many early players in the world of digital assets through his Bloomberg reporting in the 2010s, though he didn’t feel pulled to join the industry himself. Instead, he did stints at Morgan Stanley and as a speechwriter for then-U.S. Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin. He briefly served as a judicial clerk in New York before spending five years at investment firm QVIDTVM.

While professionally focused on the financial markets, he clung to his journalism roots by launching his interview blog in 2021. With the conceit that it’s inherently interesting to know the rituals and habits (opens in new tab) of successful people, Raskin has asked subjects whether they floss, binge-watch television, or believe in God.

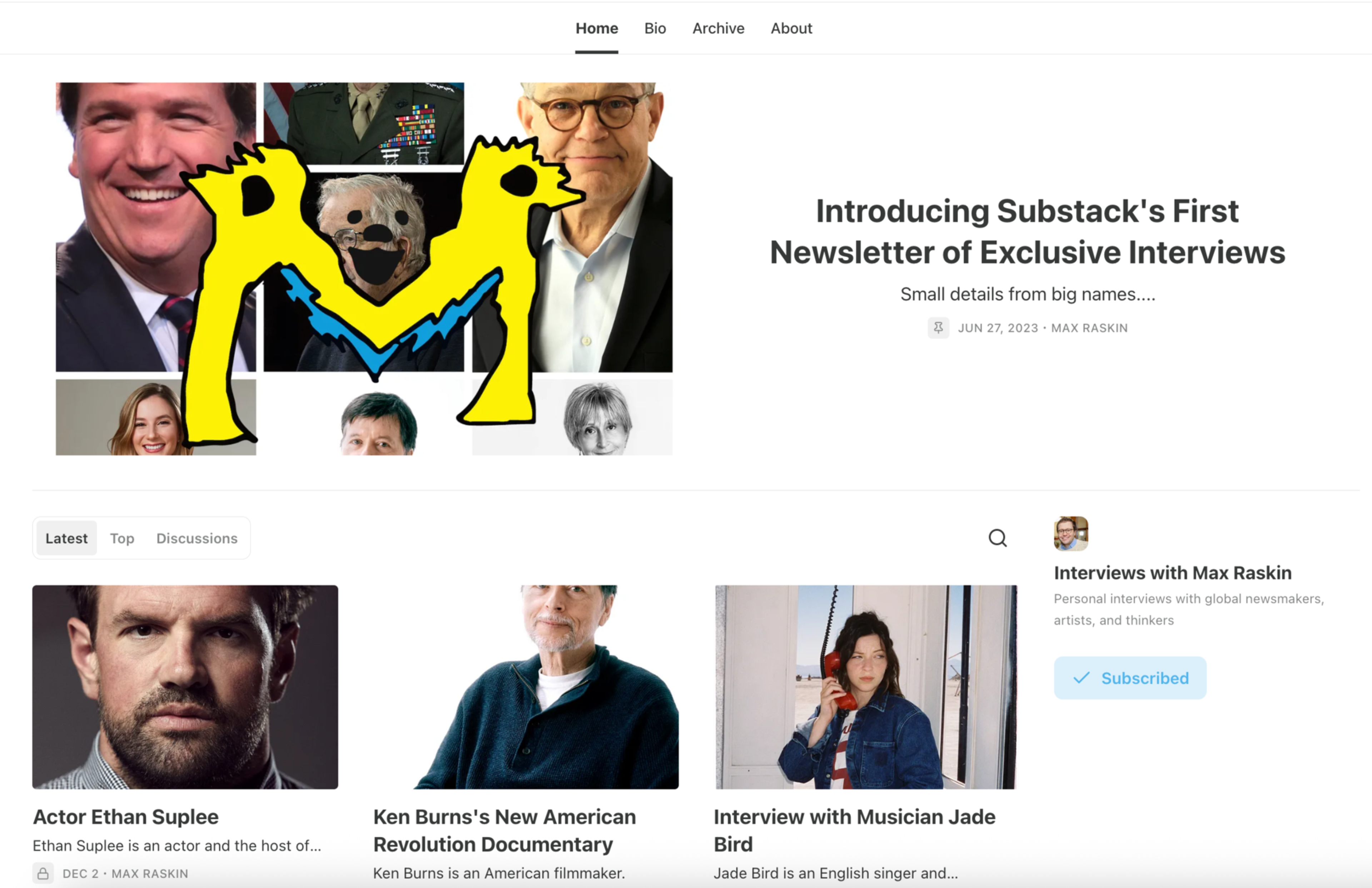

For years, Raskin has interviewed a broad range of people for his Substack blog. | Source: Screenshot

For years, Raskin has interviewed a broad range of people for his Substack blog. | Source: ScreenshotWhile quizzing Judy Blume on her views on the afterlife (she’s a nonbeliever) and Ken Burns on the best restaurant in New York (Bar Pitti), Raskin often reveals tidbits from his own life, like how he hates John Coltrane, loves Uniball pens, and, like a true San Franciscan (opens in new tab), enjoys a glass or two of Fernet. His Jewish faith comes up frequently (both he and Jacobs are observant), and he peppers his questions with references to Friedrich Hayek, Sigmund Freud, and Jerry Garcia.

“He’s one of these boy-genius types,” Henderson said, admiring Raskin’s ability to go deep on economic policy as easily as literature or music. “He could go toe-to-toe with anyone,” said Yermack.

Tech journalist turned entrepreneur Ashlee Vance met Raskin when they both worked at Bloomberg, but the two recently reconnected for an interview (opens in new tab) about hallucinogens and travel gear. Vance describes his former colleague as “this super high-energy, ambitious, and very well-connected human being.”

Raskin’s levels of energy and enthusiasm can be surpassed only by his ambitions, which can veer into moonshot territory, his friends say. One colleague described him as being “obsessed with winning a Nobel Prize” for economics. Another long shot is getting Taylor Swift as a subject for his interview series. At the very least, Raskin is known to think long-term, strategizing around a San Francisco recovery that is tracked “in decades, not years.”

Union Square’s recovery could rely on that kind of thinking, Kuiper said.

“They’re buying assets meant to hand off to your family and future generations,” he added. “That’s the kind of patience that Union Square needs.”