Voyages to the End of the World - First Things

This essay will be featured in the November 2025 issue.

Francis Bacon dreamed of abolishing disease, natural disasters, and chance itself. He also dreamed of abolishing God. Bacon hid this latter dream in New Atlantis (1626), a posthumous novella that may be read as a map for modernity, a book of prophecies, or a grimoire. New Atlantis began a secret literary debate, one later taken up by Jonathan Swift, Alan Moore, and Eiichiro Oda. Across four centuries, these writers wondered: Will science summon or suppress the Antichrist?

On the surface, Bacon presented modern science as wholly compatible with Christianity. He wrote in Novum Organum that “nature unveils her secrets only under the torture of experimentation,” a slightly more violent articulation of God’s instruction to “have dominion over . . . every living thing that moveth upon the earth” (Gen. 1:28). Bacon quoted scripture with such fluency and erudition that few question his faith today. He presented his plan to unveil nature’s secrets by means of empirical experimentation and inductive reasoning as a continuation of God’s revelation, endowing us with “new mercies” to relieve our estate.

For the pre-Christian ancients, progress ebbed and flowed as empires rose and fell. Thucydides could be forgiven for fabricating Pericles’s speeches, because the lessons of the Peloponnesian War were timeless and eternal. A Thucydidean might compare the rising Athens threatening the established Sparta to Wilhelmine Germany and Great Britain at the turn of the twentieth century, or to China and America today. A Christian, however, would recognize the prophet Daniel as the first true historian. Daniel spoke of one-time and world-historical events. He envisioned history as a succession of four kingdoms, ending with the Roman Empire. A Danielic historian would observe that neither Athens nor Sparta possessed nuclear weapons, and would discourage equating their conflicts with those of 2025. And if Daniel was the first historian, was the God of the New Testament not the first progressive? If the New Testament superseded the Old by virtue of its newness, and revelation has not concluded, then should Christians not be uniquely receptive to the possibility that “knowledge shall be increased” (Dan. 12:4), even in the profane sphere of Baconian science?

And yet for Bacon, this alliance went only so far. In New Atlantis, Bacon preached a wholly new doctrine. Much as Thomas More’s Utopia had done a century earlier, New Atlantis describes a mysterious, undiscovered island where little is as it appears. Bacon deceives his readers with plot ambiguities, cryptic references, and an unreliable narrator. He wrote New Atlantis with the finesse of a criminal mastermind, afraid of being caught but determined to document his crimes. To decode Bacon’s wicked masterpiece, we must approach it as theologian-detectives.

New Atlantis begins at the mercy of nature. A crew of European Christians sail five months west from Peru before the wind blows them to the island of Bensalem. Bensalem, Hebrew for “son of peace” or “son of safety,” is the “new Atlantis.” Like Plato’s old Atlantis, Bensalem is a wealthy island state. Wealth corrupted the old Atlantis, which became so greedy that it planned “to attack the whole of Europe, and Asia to boot” (Timaeus 24e). Zeus punished the Atlanteans’ avarice by flooding and destroying their civilization. By contrast, Bensalem seems both rich and virtuous. The Bensalemites heal the crew’s sick sailors with medicine and invite them to live on the island. This medicine is the first appearance of Bensalem’s technology. So miraculous are the inventions we later encounter that we wonder whether even Zeus could destroy the new Atlantis. With technology, Bensalem weathers natural disasters and escapes the classical kyklos of rising and falling empires. This Atlantis is not only new, but improved.

A deep state–esque research institution called “Salomon’s House” or “The College of the Six Days’ Works” develops Bensalem’s technology. Its former name honors the philosopher-king Solomon, who wrote three books of the Bible even as he violated its laws against foreign wives, whose wisdom is venerated by Christians and hermeticists alike, and whose salvation Augustine doubted. Its latter name refers to God’s six days of creation in Genesis, though whether the College honors God’s works or attempts something more ambitious remains unclear until later. Bensalem’s scientists study everything under the sun and find much that is new. They dispatch spies on twelve-year missions to steal Europe’s scientific discoveries, astonishing the sailors, who have “never heard any of the least inkling” of Bensalem. Later in the story, a Father of the College mentions internal “consultations” that determine “which of the inventions and experiences we have discovered shall be published, and which not.”

Bensalem appears friendly. It is also veiled in secrecy. A Christian priest answering the sailors’ questions about the island “must reserve some particulars, which it is not lawful for [him] to reveal.” The priest assures the nervous sailors that Bensalem is Christian. But its faith rests upon a miracle verified by Salomon’s House. Moreover, it is embedded in a diverse culture. The Bensalemites wear colorful turbans and tote Turkish canes. The etymologies of the island’s landmarks range from Greek to Latin and Hebrew. Bensalem is a world unto itself.

Bensalem bewitches the sailors. Echoing Psalm 137:6, they tell the priest that “our tongues should first cleave to the roofs of our mouths, ere we should forget either his reverend person or this whole nation in our prayers.” The quoted Israelites were recalling the holy city of Jerusalem, from which they were exiled. Geographically, the sailors are also far from Jerusalem—their five-month voyage west from Peru would locate them near French Polynesia, Jerusalem’s antipode. Perhaps the sailors are unaware that, from Jerusalem’s perspective, Bensalem lies at the end of the world. In any case, Bensalem becomes their holy land. Eventually, the Bensalemites’ “humanity . . . make[s the sailors] forget all that was dear to [them] in [their] own countries.”

Bacon does not identify the story’s narrator, but a sermonic speech early in the narrative suggests that he is the ship’s chaplain. His crew’s quasi-religious conversion should unnerve him. But he is delinquent in his duties. He notes that “six or seven days” pass on the island. We deduce that by traveling west the sailors have lost a day, and the chaplain no longer knows which day is Sunday. At this point, the chaplain meets an enrapturing man named Joabin. Joabin, whose name is plural, is “a Jew and circumcised” and descends from Nachoran, a forgotten son of Abraham. Joabin sees in Christ “many high attributes.” The narrator calls Joabin “wise,” an epithet withheld from every other living Bensalemite, and “learned, and of great policy, and excellently seen in the laws and customs” of Bensalem. Joabin describes Bensalem’s sexual mores, and though the island celebrates fecundity, he cryptically names it “the virgin of the world.”

The virgin island seduces the chaplain. He tells Joabin that “the righteousness of Bensalem [is] greater than the righteousness of Europe.” A messenger appears, ushering Joabin away. He returns the next morning to announce the arrival of a reclusive Father of the College, unseen “this dozen years.” Bensalem deploys its spies on twelve-year reconnaissance tours—has the Father returned from Europe? He enters with a triumphal procession, bedecked in jewels and bearing an expression “as if he pitied men.” Three days later, Joabin shares good news: Having learned of the crew’s presence in Bensalem, the Father intends to speak with one of the sailors. On the appointed “day and hour” (see Matt. 24:36), the sailors elect their chaplain to represent them. Bensalem’s eerie drama will culminate in the induction of the narrator, and the reader, into the mysteries of the College.

“The end of our foundation,” the Father reveals, “is the knowledge of causes, and secret motions of things; and the enlarging of the bounds of human empire, to the effecting of all things possible.” This sounds grandiose to an atheist, but it should have struck the chaplain as sacrilegious, for the Bible teaches that “with God”—and only God—“all things are possible” (Matt. 19:26). The Father continues, revealing the facilities, tools, and methods by which the College pursues its ambitions and the staggering fruits of its toil. The College owns reproductions of every ecosystem; towers three miles high (taller, per Strabo, than the Tower of Babel); kitchens, bakeries, and brewhouses; observatories and laboratories; “perspective-houses,” “sound-houses,” and “perfume-houses” to delight and deceive the senses; and “engine-houses” building planes and submarines. The College wields near-omnipotence over the natural world. We might wonder whether anyone lands ashore on Bensalem except by the grace of Salomon’s House and conclude that the winds that set the story in motion were not quite so random as they appeared.

The Father then describes how the College is organized. It divides its labor among “several employments and offices,” including spies, innovators, and natural philosophers. Unexpectedly, the Father announces that the narrator may publish his words “for the good of other nations.” The story ends when the Father pays the chaplain two thousand ducats, which he accepts, renouncing any vestige of his Christian faith.

Many of Bensalem’s mysteries have been solved. But one question remains: Who actually runs Bensalem? Earlier in the story, we heard briefly of a “king” but learned nothing of him. We might assume the king is a figurehead controlled by Salomon’s House. But the College’s division of labor precludes any one fellow from directing it. Its bureaucracy requires the management of a general secretary. Only wise Joabin, intimately acquainted with the governance of Bensalem, could fill this role. And as we reconsider the clues Bacon has left us about Joabin, we uncover Bensalem’s darkest secret: Joabin is the biblical Antichrist.

The chaplain has told us that Joabin is Jewish and circumcised. A good Baconian, the chaplain empirically discovered the latter fact under circumstances too scandalous to print. Joabin’s being Jewish and gay fulfills two of Daniel’s Antichrist prophecies: “Neither shall he regard the God of his fathers, nor the desire of women” (Dan. 11:37). We also know that Joabin descends from a lost tribe of Israel, implied of the Antichrist in Revelation 7:4–8. And in Paul’s telling, the words that herald the Antichrist’s appearance are “Peace and safety!” (1 Thess. 5:3). As we recall, Bensalem translates as “son of peace” or “son of safety.” We should also consider Joabin’s odd boast of Bensalem’s virginity in light of Saint Jerome’s speculation that the Antichrist would be born of a virgin. In the apocryphal “Testament of Solomon,” Solomon commanded demons to build his temple. Salomon’s House, the temple rebuilt, employs the same labor.

We ponder again the Father’s decision to allow the publication of his speech and to reveal Bensalem to the world. It is in part a metafictional device explaining how Bacon’s book came to us. But its meaning extends further. We return to the Father’s descriptions of Bensalem’s weaponry, “stronger and more violent” than any in Europe. This arsenal might warn off potential invaders. But why warn invaders who are unaware that Bensalem even exists? We suggest a more sinister explanation. The Father is indeed warning of an invasion—an invasion coming from, not to, Bensalem.

New Atlantis ends by pronouncing that “The rest was not perfected”—the book is formally unfinished. So too was Plato’s Critias, the story of the old Atlantis. What would have followed in Plato’s story was a speech from Zeus explaining why he felled the Atlanteans. Bacon’s story omits not speech, but action: the establishment of a global, technocratic empire ruled by the Antichrist.

II.

In 1953, Josef Pieper wrote that “The name Antichrist rings strangely on the modern ear.” In 2025, it sounds antediluvian. Writing around the time of Bacon’s youth, the bishop of Salisbury John Jewel declared that “There is none, neither old nor young, neither learned nor unlearned, but he hath heard of Antichrist.” Our amnesia today would not merely have surprised Christians in centuries past—it would have been understood as a sign of the Antichrist’s imminent arrival.

Bacon enthroned the Antichrist in his utopia. What lies beneath the Christian surface of Bacon’s teaching? Are Bensalem’s colorful clothes and rituals the hieratic pomp of a Satanic mass? The invocation of a prisca theologia? Or mere window-dressing that disguises atheist materialism? We suspect that Bacon was a closet atheist who invoked the Antichrist playfully, much as his secretary, Thomas Hobbes, named his Leviathan after a demon. But a Christian reader should worry that such play is not wholly without consequence, and that as Bacon dabbled in the demonic, the demonic dabbled in him.

In any case, even Bacon could not have imagined a world so biblically illiterate as to interpret Bensalem as Christian. To understand Bensalem, we turn to the Antichrist’s biblical origins. An evil king or anti-messiah appears in the Old Testament books of Isaiah, Ezekiel, and Daniel. Daniel imagined the four great empires of human history as beasts, the last of which has “ten horns” and represents the Roman Empire (Dan. 7:7). These ten horns, an angel explains, symbolize “ten kings that shall arise” as Rome falls (Dan. 7:24). Daniel prophesied that these ten would be subjugated by an eleventh: “I considered the horns, and, behold, there came up among them another little horn . . . and, behold, in this horn were eyes like the eyes of a man, and a mouth speaking great things” (Dan. 7:8). This “little horn” will rule the world’s powers and principalities for three and a half years before the apocalypse.

Hippolytus, Origen, and other Church Fathers understood Daniel’s final global tyrant as the New Testament’s Antichrist. In the Olivet Discourse of the synoptic Gospels, Christ warns of “false Christs” emerging in our final days. The Johannine epistles announce that “as ye have heard that antichrist shall come, even now there are many antichrists” (1 John 2:18). Paul calls the Antichrist the “man of sin” and “son of perdition” (2 Thess. 2:3). In his most colorful and eldritch form, the Antichrist appears in Revelation as a proto-Lovecraftian sea monster: “And I stood upon the sand of the sea, and saw a beast rise up out of the sea, having seven heads and ten horns” (Rev. 13:1).

Christians debated these prophecies for millennia. Who was the Antichrist? When would he arrive? What would he preach? Pamphleteers and polemicists plucked him from the obscurity of theology to attack their enemies. The Roman emperors Nero and Domitian, the Prophet Muhammad, Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II, various popes, Tsar Peter the Great, Napoleon Bonaparte, Adolf Hitler, and Franklin D. Roosevelt were all popular suspects. Some authors filled the gaps in the Antichrist legend with literature—Francis Bacon among them.

One question ripe for literary treatment is how the Antichrist will take over the world. Joabin imagined a path from empiricism to empire by way of technology, especially the submarines and planes of Bensalem’s engine-houses. Without such technology, it is hard to conceive of any nation conquering a planet on which 71 percent of the surface is covered by water, a planet on which control of the oceans is control of the world. Since the earliest chapters of biblical history, water has been inhospitable to human life, and only through divine intervention did we survive its chaos (Gen. 1:9). The medieval encyclopedia Liber Floridus shows the Antichrist surfing waves atop the sea demon Leviathan. In the penultimate chapter of Revelation, after the Antichrist’s defeat and Christ’s return, John gazes upon a universe remade: “And I saw a new heaven and a new earth . . . and there was no more sea” (Rev. 21:1).

The Antichrist atop Leviathan, Liber Floridus (c. 1120)

The Antichrist atop Leviathan, Liber Floridus (c. 1120)

For Bacon, control of the oceans was too important to leave to God. He wrote New Atlantis at the tail end of the Age of Discovery, after men like Christopher Columbus, Vasco da Gama, and Sir Francis Drake had extended human empire to the four corners of the earth. Bacon argued in Parliament for the seizure of Spanish territories, including Peru, the New Atlantis sailors’ port of departure. Two centuries would pass before the Duke of Wellington triumphed at Waterloo and Britain overtook France as the world’s greatest empire. At that point, between London’s Royal Society (which had anointed Bacon its “Moses”), the Industrial Revolution, British naval supremacy, and the Pax Britannica (“Peace and safety!”), one scarcely exaggerates in declaring the realization of Bensalem’s planetary empire.

The frontispiece of Bacon’s Great Instauration depicts a ship passing through the pillars of Hercules above a quote from Daniel’s apocalyptic prophecy: Multi pertransibunt & augebitur scientia (“Many shall run to and fro, and knowledge shall be increased”). But if Bacon believed that modernity was the end of the world, it was merely the end of the old world, the world bedeviled by the vagaries of chance and nature. For Bacon, the rivers of blood in Revelation flow not through humanity’s future but through its past, through the millennia of ignorance and scarcity that had been man’s lot since he first walked the earth. Transcending this miserable history, Bensalem is almost indistinguishable from Heaven.

Bacon’s Instauratio Magna (1620)

Bacon’s Instauratio Magna (1620)

If Bensalem is uncomfortably close to Heaven, how close are the Antichrist and Christ? The tenth-century monk Adso’s “biography” of the Antichrist stresses his disunity with Christ: “Christ came as a humble man; [Antichrist] will come as a proud one. . . . He will always exalt the impious and always teach vices which are opposite to virtues.” Adso names Antiochus, Nero, and Domitian as forerunners of the Antichrist, or what Thomas Aquinas called quasi figurae Antichristi. But according to Matthew 24:24, the Antichrist may “deceive the very elect.” We recall that Joabin recognized in Christ “many high attributes.” Hippolytus warned that “The Savior was manifested as a lamb, so [the Antichrist] too will appear as a lamb without; within he is a wolf.” In Luca Signorelli’s Renaissance fresco The Sermon and Deeds of the Antichrist, the Antichrist appears physically identical to Christ.

Luca Signorelli, “Sermon and Deeds of the Antichrist” (1504)

Luca Signorelli, “Sermon and Deeds of the Antichrist” (1504)

III.

Jonathan Swift tried to exorcise Baconian Antichrist-worship from England. Gulliver’s Travels agreed with New Atlantis on one point: The ancient hunger for knowledge of God had competition from the modern thirst for knowledge of science. In this quarrel between ancients and moderns, Swift sided with the former.

Gulliver’s Travels takes us on four voyages to fictional countries bearing scandalous similarities to eighteenth-century England. In his depictions of the Lilliputians, Brobdingnagians, Laputans, and Houyhnhnms, Swift lampoons the Whig party, the Tory party, English law, the city of London, Cartesian dualism, doctors, dancers, and many other people, movements, and institutions besides. Swift’s misanthropy borders on nihilism. But as is the case with all satirists, we learn as much from whom Swift spares as from whom he scorns—and Gulliver’s Travels never criticizes Christianity. Though in 2025 we think of Gulliver’s Travels as a comedy, for Swift’s friend Alexander Pope it was the work of an “Avenging Angel of wrath.” The Anglican clergyman Swift was a comedian in one breath and a fire-and-brimstone preacher in the next.

Gulliver claims he is a good Christian. We doubt him, as we doubt Bacon’s chaplain. Gulliver’s first name, Lemuel, translates from Hebrew as “devoted to God.” But “Gulliver” sounds like “gullible.” Swift quotes Lucretius on the title page of the 1735 edition: “vulgus abhorret ab his.” In its original context, Lucretius’s quote describes the horrors of a godless cosmos, horrors to which Swift will expose us. The words “splendide mendax” appear below Gulliver’s frontispiece portrait—“nobly untruthful.” In the novel’s final chapter, Gulliver reflects on an earlier promise to “strictly adhere to Truth” and quotes Sinon from Virgil’s Aeneid. Sinon was the Greek who convinced the Trojans to open their gates to the Trojan horse: one of literature’s great liars.

Gulliver’s third and fourth voyages attack two atheisms—scientific and philosophical. At the outset of the third voyage, Gulliver is captured by Japanese pirates. He bravely affirms his faith, despite knowing that Japan’s Tokugawa shogunate executes Christians. The pirates spare Gulliver and set him onto the path of Laputa, a flying island engineered by modern science. A talented linguist, Gulliver observes similarities between the Laputan language and Italian. In Italian, la puttana translates as “the whore.”

Gulliver does not notice this. He is distracted by the grotesque Laputans, heads and eyes askew, caricatures of dreamy mathematicians and astronomers. The Laputans are “so taken up with intense Speculations” that they thrash each other with “Flappers” when conversing. When Gulliver declines to be beaten, the Laputans conclude he must be stupid. But the Laputans’ enlightenment brings them no happiness. They “never [enjoy] a Minute’s Peace of Mind,” fearing that the sun will burn up the earth, or burn itself out, or that a comet will collide with earth and “destroy us.” The Laputans’ enthrallment to celestial events beyond their control rebuts Bensalem, whose survival is not guaranteed even with complete dominion over Earth.

While the Laputans gaze up at the cosmos, their king oversees the more mundane matter of taxation. He administers divine punishment to delinquent taxpayers on the island of Balnibarbi below, blotting out the sun and “afflict[ing] the Inhabitants with Dearth and Diseases.” When the people resist, the king threatens to let the island “drop directly upon their Heads.” But the king hesitates to follow through, because towns with “high Spires, or Pillars of Stone” might destroy Laputa. On Swift’s illustrated map of Balnibarbi, we see that these “high Spires” are churches.

Swift’s map of Balnibarbi

Swift’s map of Balnibarbi

The totalitarian King delivering judgment from the skies reminded the scholar Anne Barbeau Gardiner of the Antichrist. His perch “above the Region of Clouds and Vapours” fulfills a prophecy of the Antichrist’s false ascension into Heaven (see Isa. 14:14 and 2 Thess. 2:4) and matches Satan’s description as “the prince of the power of the air” (Eph. 2:2). Isaiah 47:13 tells of Babylon’s “astrologers [and] stargazers,” who will be incinerated in the end times, just as the Laputan astrologers predict the arrival of the next comet. Revelation 18:8 similarly prophesies that la puttana of Babylon “shall be utterly burned with fire.”

Laputa’s high-flying science is evil, but Balnibarbian science simply doesn’t work. At Balnibarbi’s Academy of Lagado, an institution like Bensalem’s College, “Professors contrive new Rules and Methods. . . . All the Fruits of the Earth shall come to Maturity at whatever Season we think fit to chuse . . . with innumerable other happy Proposals.” The fruits of Bensalem’s research are cornucopian; Lagado’s wither on the vine. “The only Inconvenience,” Gulliver notes, “is that none of these Projects are yet brought to Perfection; and in the mean time, the whole Country lies miserably waste, the Houses in Ruins, and the People without Food or Cloaths” (see Matt. 26:11). One scientist is unsuccessfully “extracting Sun-Beams out of Cucumbers.” A mathematician instructs his students to digest his lessons—literally, by writing them “on a thin Wafer.” This parodies the Eucharist and Revelation 10:10, wherein John learns an angel’s prophecy by eating a scroll.

Nowhere does the Bible promise luminous cucumbers or edible math lessons. Insofar as Lagado cannot provide them, we are merely amused. But what of eternal life? Though it fell short of immortality, Salomon’s House achieved the “prolongation of life in some hermits.” When Gulliver visits Luggnagg, a Balnibarbian city, he is invited to meet the Struldbrugs, an immortal race born “with a red circular Spot in the Forehead” like the mark of the Antichrist (Rev. 13:16–17). Thrilled, Gulliver imagines that if he were a Struldbrug he would make untold scientific discoveries. Gulliver is chastened by a “Gentleman . . . with a Sort of a Smile, which usually ariseth from Pity to the Ignorant,” recalling Bensalem’s Father’s “aspect as if he pitied men.” The Struldbrugs, the gentleman informs Gulliver, have eternal lifespans but normal human healthspans. They age into impotence and senility. At funerals, Struldbrugs “lament and repine that others are gone to an Harbour of Rest, to which they themselves never can hope to arrive.” They are the wretched subjects of the Antichrist described in Revelation 9:6: “in those days shall men seek death, and shall not find it; and shall desire to die, and death shall flee from them.”

Gulliver encounters two other quasi figurae Antichristi—a sorcerer in Glubbdubdrib who raises the dead (Dan. 12:2) and the King of Luggnagg, who demands that Gulliver “lick the Dust before his Footstool” (Isa. 49:23). Gulliver escapes these men of sin with his body intact. His soul is another matter. At the beginning of the voyage to Japan, Gulliver avowed his Christianity to the Japanese pirates. At the end, he impersonates an atheist Dutchman and pretends to have performed the Fumi-e—the trampling of a crucifix. The apostate Gulliver is primed for his fourth voyage, to a land governed by horses.

Science failed to relieve man’s estate in Balnibarbi, so it is a relief to arrive in the country of the Houyhnhnms, which knows no science at all. Psalm 32:9 warns: “Be ye not as the horse, or as the mule, which have no understanding.” But this seems an inaccurate description of the Houyhnhnms, who remind Gulliver of philosophers. That is exactly what they are—St. Augustine and John Donne both interpreted Psalm 32:9 as referring to philosophers who reason without faith.

The Houyhnhnms are appalled to learn that Gulliver’s clothes are not part of his body. Their confusion saves Gulliver some trouble, because if not for his clothes, the Houyhnhnms would have taken him for a Yahoo, a bipedal species enslaved by the Houyhnhnms. The Yahoos sicken Gulliver, who “never saw any sensitive Being so detestable on all Accounts.” He is undisturbed to learn that the Houyhnhnms slaughtered most of the first Yahoos in a “general Hunting.” When he realizes that the Yahoos descend from Europeans, and that he himself is a Yahoo, he “turn[s] away [his] Face in Horror and Detestation” upon seeing his reflection. Yahoo comes from “Yahweh”—the Yahoos are Christians enduring the great tribulation.

Christians resisted tyranny in Balnibarbi; in Houyhnhnmland, they are in danger of genocide. The Houyhnhnm parliament only ever debates one question: “Whether the Yahoos should be exterminated from the Face of the Earth.” Eventually, the Houyhnhnms discover that Gulliver is a Yahoo and demand that he remain in Houyhnhnmland a slave or depart. Gulliver mournfully decides to leave. He builds a canoe “with the Skins of Yahoos,” including “the youngest [he] could get, the older being too tough and thick.” For Swift, atheism culminates not in Bensalem’s hierarchical prosperity, but Houyhnhnmland’s totalitarian butchery. Both Laputan techno-rationalism and Houyhnhnm philosophical reason are Trojan horses concealing the apocalypse, shepherded into Christendom by liars like Francis Bacon and fools like Lemuel Gulliver.

Gulliver ends his travels a lonely misanthrope. Like Bacon’s sailors, he has forgotten “all that was dear” to him in Europe. But whereas Bacon’s sailors were enlightened, Gulliver is embittered and confused. He returns to England and cannot stand to look at his Yahoo wife (an “odious Animal”). He yearns only to contemplate the Houyhnhnms. He ends his story proudly forbidding any prideful Yahoo from “presum[ing] to come in [his] Sight,” a perversion of the Anglican Prayer of Humble Access (“We do not presume to come to this thy Table, O merciful Lord”).

IV.

If we are to judge by the popularity of their books, Swift won his debate with Bacon. Millions of readers giggle along to Gulliver’s Travels even today. If we are to judge by the influence of their ideas, Bacon had the last laugh. Swift’s concerns about scientific fraud hold up depressingly well today. But judged holistically, Baconian science fulfilled almost all of Bacon’s prophecies. Swift scoffed at scientists’ attempt to illuminate the world with cucumbers, but in 1879, Edison succeeded with the incandescent light bulb. Had Gulliver’s grandchildren wished to replicate his voyages, they could have done so quickly and safely, thanks to the copper-plated hulls and iron joints that sped up English ships in the 1780s and ’90s, to say nothing of the iron steamships that arrived a few decades later. The nineteenth century’s vaccines, automobiles, telephones, and steam-powered locomotives vindicate Bensalem, not Lagado.

Swift’s flying island did, however, foresee science’s “dual-use” problem. Samuel Colt designed the first revolver in 1830, just three decades before Richard Gatling was to build a machine gun, followed six years later by Alfred Nobel’s dynamite. Nobel, whose Nobel Prizes eased his guilty conscience, understood better than most where this was leading. The terrible carnage of World War I did not forestall an even deadlier successor conflict. By 1943, many were ready for peace. Onetime Republican presidential candidate Wendell Willkie published One World, a travelogue whitewashing Stalin’s liquidations (Stalin, we learn, “dresses in light pastel shades”) and arguing for the desirability and inevitability of world government. One World became the bestselling work of nonfiction in American history.

If the hail of machine-gun fire at the Somme wounded our Baconian optimism, nuclear weapons blew it up entirely. In the dual sense of termination and culmination, Los Alamos was the end of Baconian science. Science had created the means to end the world, and now the world sought the means to end science. One World became “One World or None?,” a 1946 propaganda film that framed world government as no longer a distant hope but an immediate necessity. “The United Nations must establish a worldwide control of atomic energy,” booms the film’s narrator. “The choice is clear: It is life or death.” J. Robert Oppenheimer concurred: “Many have said that without world government there could be no permanent peace, and without peace there would be atomic warfare. I think one must agree with this.”

The Cold War threw a curtain over the “one world” project. But in 1963, less than a year after the Cuban Missile Crisis, the cold warrior John F. Kennedy got cold feet and revived the idea. In a commencement speech to the graduating class of American University, Kennedy dreamed of “not merely peace in our time but peace for all time.” This peace would be enforced by an international “system capable of resolving disputes . . . and of creating conditions under which arms can finally be abolished.” Some who suspect U.S. government involvement in Kennedy’s assassination believe this speech sealed his fate.

Two decades later, to awaken a world sleepwalking into Armageddon, Alan Moore wrote the superhero comic Watchmen (1986–87), a late-modern illustration of the Antichrist. Watchmen unfolds in a parallel timeline. The Cold War rages on, liberal internationalism appears politically dead, and in 1985, the year the series begins, Richard Nixon is serving his fifth term as president.

Moore’s superheroes are “watch men” in two senses: They watch over the world, and they are men of our final hour. A “grievous vision” in the book of Isaiah, from which Moore took his title, combines these two meanings: “For thus the Lord said unto me, Go, set a watchman, let him declare what he seeth” (Isa. 21:2, 6). Isaiah’s watchman sees the apocalyptic fall of Babylon, and from the opening, bloody panels of Watchmen, the same fate seemingly awaits Moore’s world. Every issue of Watchmen ends with a doomsday clock ticking toward midnight. In a nuclear age, Moore’s superheroes are faintly ridiculous. Except for one, they have no superpowers. But these high-agency individuals are dangerous, too. “Who watches the watchmen?” chant public protestors, quoting Juvenal. In response, the Keene Act of 1977 outlawed superheroes. When the story begins, somebody is murdering the watchmen, one by one.

Watchmen’s only hero with superpowers is Jonathan Osterman, a nuclear physicist. A laboratory accident transformed Osterman into “Doctor Manhattan,” a being capable of manipulating subatomic matter and seeing through time, a synthesis of artificial general intelligence and a thermonuclear weapon. Manhattan’s very existence intensifies the apocalyptic logic of late modernity. If the threat of Manhattan cannot de-escalate the Cold War, Moore wonders, then what can?

Watchmen’s narrator is Rorschach, a hardboiled superhero somewhere between Bruce Wayne and Ayn Rand. By day, Rorschach is an apocalyptic street crier, half-convinced the world deserves its fate. But he believes in good and evil. The deaths of Rorschach’s fellow superheroes disturb him, and he decides to investigate. To Moore’s frustration, the Manichaean Rorschach is his most popular character.

Watchmen slips between timelines, settings, and literary genres. Recurring symbols lend the story its otherwise faint linearity. We sense that Rorschach’s investigation is tied to the fate of the world. Eventually, we are proven right: Rorschach discovers that Adrian Veidt, a billionaire industrialist, is behind the killings and organized a botched attempt on his own life as a false flag.

Veidt is a type of Antichrist. His superhero moniker is Ozymandias, the Greek name for the Egyptian Pharaoh Rameses II and an allusion to Percy Shelley’s poem (“Ozymandias”). As a young man, Ozymandias smoked Tibetan hashish and dreamed of surpassing Alexander the Great by uniting the world. He is a self-proclaimed pacifist and vegetarian, in some ways more Christian than Christ and the sort of figure who might “deceive the very elect.”

Adrian Veidt and his alien invasion

Adrian Veidt and his alien invasion

To take over the world, Veidt stages a fake alien invasion. On a paradisal island like Bensalem, he builds a giant, telekinetic “alien” and drops it onto a concert by a band named Pale Horse (Rev. 6:8), killing millions in New York City. The Americans and Soviets establish a world government to protect the planet. Rorschach learns of Veidt’s plan only after it has succeeded, and he resolves to tell the world what happened, even at the risk of ending the armistice. “There is good and evil,” says Rorschach, “and evil must be punished. Even in the face of Armageddon I shall not compromise in this.” The otherwise meditative Doctor Manhattan disagrees and kills Rorschach. As though to trigger Christian readers, Manhattan then walks on water. Posters celebrating “One World, One Accord” announce Veidt’s victory: Earth is peaceful and safe. Veidt helps New York to rebuild and emblazons the Veidt Enterprises logo across the city (see Rev. 13:17).

Moore’s great achievement is his updating of Bacon’s pro-science Antichrist for late modernity. Our nuclear world produces endless Hollywood sci-fi dystopias and no longer believes that Baconian science can bring about “peace and safety.” Ozymandias knows that the way to secure power is to scare us about the future. Moore might resist the comparison, but he agrees with Carl Schmitt, who obsessed over the Pauline epistles and doubted that “humanity” could unite behind a political project, “because it has no enemy, at least not on this planet.”

Watchmen triumphs as literature and fails as philosophy or theology. Moore can only ask, not answer, Juvenal’s question, “Who watches the watchmen?” For in Moore’s godless world, the question begets an infinite regress. Who watches the sponsors of the Keene Act? Who watches Nixon? Before Watchmen concludes, it seems that Veidt, the great man to end all great men, has solved the problem. But in Watchmen’s final panels, Rorschach’s diary exposing Veidt’s plot sits in the submissions pile of a newspaper. Doctor Manhattan tells Veidt that “nothing ever ends,” suggesting that Moore’s Ozymandias will share the fate of Shelley’s, and of the biblical Antichrist. But in the Bible, God ends the suffering (Matt. 24:22). For Moore and Shelley, the only salvation is the impermanence of things. Though he loves antiquity, Veidt is an early modern like Bacon, who hoped to conquer chance and establish a new Earth once and for all. The late modern Moore has given up on this project. He rejects Christ and, ambivalent about Antichrist, resigns himself to fatalism.

One final detail in Watchmen bears mentioning. In Moore’s alternate history, superheroes threaten public order. As the apocalypse approaches, readers abandon superhero comics for pirate comics, particularly a series entitled Tales of the Black Freighter. Like superheroes, pirates are daring and individualistic. Unlike superheroes, they use their powers for evil. Or, more accurately, they use their powers to defy the ruling authorities. One man’s superhero, Moore says, is another government’s pirate.

V.

Four years after Watchmen ended, so did the Cold War. President George H. W. Bush declared the beginning of a “new world order,” safe from great-power conflict. His successor, Bill Clinton, disarmed to save on a “peace dividend” and accelerated globalization with trade deals. In this tranquil time, the swashbuckling Eiichiro Oda began writing One Piece, a manga that—twenty-eight years and more than 1,100 chapters later—has entered its “final saga.”

If you have not heard of One Piece, your children probably have. One Piece has sold more than 570 million copies, not counting the millions of fans who read the series online or watch the even more popular anime adaptation. The r/OnePiece subreddit discussion forum has 5.2 million followers, more than any other subreddit for a work of fiction (for comparison, r/StarWars has 4.6 million followers; r/HarryPotter has 3.6 million).

Oda’s readers love not only his action sequences and Tolkien-esque worldbuilding, but his esoteric writing. The exegesis of Oda’s allusions, puns, numerological puzzles, and other mysteries is their shared project. Over hundreds of chapters, Oda’s piecemeal revelations cohere into a grand linear history of the Antichrist, superior on every decisive point to Watchmen.

The question driving Oda’s epic is who rules the world. We follow a crew of young pirates, led by Captain Luffy, seeking a hidden treasure called the “One Piece.” Whoever finds the one piece will be “King of the Pirates,” though we do not know exactly what that means. In the meantime, a World Government has tyrannized the oceans for eight hundred years, following a mysterious “Void Century” whose study is forbidden. In chapter 233, Oda introduces the oligarchic gerontocracy atop this government: “five elders” (Gorosei) who call themselves saints. Six hundred seventy-five chapters later, we learn that these gerontocrats worship a secret sovereign named Imu. An anti-government rebel named Ivankov deduces from a book called “Genesis” that Imu is “Nerona Imu,” a founding member of the World Government. Imu manages its empire with an amphibious military, a secret police, and special forces (“God’s Knights”). Almost offhandedly, we learn in chapter 1,115 that the World Government’s original name was “the allied powers.”

As the dictator of a World Government, Imu resembles the Antichrist, a resemblance that is anything but accidental. The name “Nerona” reminds us of the Roman emperor Nero, who died by suicide in a.d. 68. Per the historian Suetonius, conspiracy theorists whispered that Nero’s death had been faked: “They published proclamations in his name, as if he were still alive, and would shortly return to Rome” (Nero 57). Tacitus wrote of imposter Neros leading rebellions (Histories 2.8), and the Sibylline Oracles spoke of a matricide king who would return to Rome, “making himself equal to God.”

From these rumors emerged the legend of Nero redivivus, a zombie Nero resurrected in a parody of Christ. This legend may have informed the writing of Revelation. Saint John identified 666 as the number of the beast, and Nero’s Hebrew name, Neron Kaisar, has a gematric value of 666. Early Christians adopted the idea: “This [Antichrist] is Nero . . . from hidden places at the very end of the world he shall return” (Commodian, Carmen Apologeticum). By the Middle Ages, most theologians accepted that Nero was dead and acknowledged him as a quasi figura Antichristi. Per Joachim of Fiore, “the Beast from the Sea is held to be a great king . . . who is like Nero and almost emperor of the whole world” (Exposition, fol. 168ra).

As for “Imu,” spelled backwards it becomes “umi,” Japanese for “the sea,” making Nerona Imu “Nero the sea” beast. The sea covers even more of Oda’s “Blue Planet” than it does our own planet. It is both the path to treasure and the battlefield on which control over the world is decided. It is especially perilous for those Faustian characters who have eaten “Devil Fruits,” granting them bizarre powers. Luffy, for example, can stretch his body like rubber—at the price of being unable to swim.

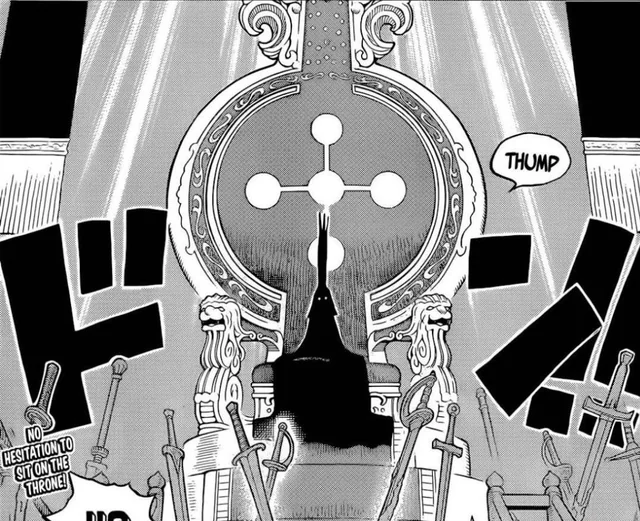

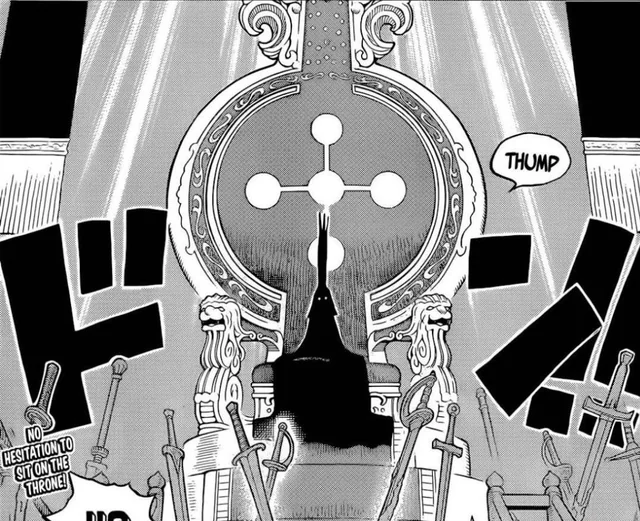

Imu wears a hood, so we can only speculate as to its real appearance. But for now, Imu is a black spike with eyes, a mouth, and a crown—literally Daniel’s “little horn” with “eyes like the eyes of a man, and a mouth.” Like Isaiah’s King of Babylon, who “exalt[s his] throne above the stars of God,” Imu inhabits a “Holy Land” at the world’s highest point of elevation. If readers doubted the World Government’s holiness, the recent appearance of a Gorosei was damning beyond suspicion. A pentagram heralded his arrival in a flash of lightning, mimicking Satan’s descent in Luke 10:18.

Nerona Imu. “In this horn were eyes like the eyes of man, and a mouth speaking great things.”

Nerona Imu. “In this horn were eyes like the eyes of man, and a mouth speaking great things.”

If Imu is Antichrist, Luffy is Christ. For hundreds of chapters, Luffy seems nothing more than the happy-go-lucky captain of his crew, attracting disciples and dethroning tyrants. The observation that his trademark image, a red-striped straw hat, resembles a bloody crown of thorns might seem like a stretch. But in One Piece’s final saga, Oda’s Christian apocalyptic imagery has become undeniable. Around chapter 1,000, Luffy and his allies battle their most powerful rivals: a dragon named Kaidou and a soul-devouring cannibal with dozens of children named “Big Mom.” Revelation depicts Christ confronting a dragon representing Satan and the Whore of Babylon (a “woman drunken with the blood of the saints” like a cannibal [Rev. 17:6]). Kaidou nearly defeats Luffy. But Luffy transforms into the Christ of Revelation 1:14: “His head and his hairs were white like wool, as white as snow; and his eyes were as a flame of fire.”

Christlike Luffy

Christlike Luffy

Big Mom, the Whore of Babylon.

Big Mom, the Whore of Babylon.

Kaidou, the dragon.

Kaidou, the dragon.

Christlike Luffy defeats Kaidou and Big Mom. Like Revelation’s dragon, they are “cast alive into a lake of fire burning with brimstone” (Rev. 19:20). The transformed Luffy reminds Imu of a messianic figure from the Void Century named “Joy Boy,” the first pirate. The return of Joy Boy, a divine pirate, would rebuke the divinized Imu, just as Christ the Son of God rebuked Caesar Augustus, son of the divinized Caesar. A divine “king of the pirates” would imperil the World Government’s legitimacy. Later in the story, we meet a freed slave named Kuma, whose father taught him to await the return of a sun god named Nika. In our world, Byzantine Christians emblazoned the Christogram “IC XC” alongside the Greek word “Nika” (meaning “Jesus Christ conquers”) on churches and icons. Kuma’s fellow slaves, hunted by the World Government like Yahoos, take comfort in his story.

Moore repackaged the logic of “One World or None?” to ask: Ozymandias or nuclear war? Since Watchmen ended and One Piece began, apocalyptic fears—of artificial intelligence, climate change, and bioweapons—have proliferated. Moore’s argument might seem even stronger today. But Oda knows how to rebut it. Moore’s jeremiad transpires minutes before midnight; Oda brings us eight centuries into the reign of the Antichrist. Oda takes the dangers of science seriously: Imu uses a weapon resembling a nuclear bomb to “make fire come down from heaven on the earth” (Rev. 13:13). But Vegapunk, the Einsteinian scientist behind the weapon, believes in science’s salvific power. In chapter 1,113, he tells the world of lost technology suppressed by the World Government. A child’s illustration from the Void Century, discovered in chapter 1,138, shows that this old technology resembles our own. Enraged, the World Government orders Vegapunk’s execution.

For philosophy, the question “One world or none?” has but one answer. Better red than dead. Theology reformulates the question: “Antichrist or Armageddon?” “Neither,” the Christian replies. He prays for new miracles, new technologies, and strange new possibilities. Oda reminds us to hope for such fantastical new things by defying us to reason out how One Piece will end. Neither the apocalyptic anarchy of an ocean teeming with pirates nor the sclerotic gerontocracy of Imu’s World Government can last. Oda must reveal a narrow, third way. “As little children” (Matt. 18:3), we have faith that he will.