A Regime On The Brink

Israel’s lightning campaign has shattered Iran’s air defences, decapitated its military command, and sent members of the regime’s leadership fleeing to Russia. With the last fortified nuclear site at Fordow remaining untouched, a moment of global consequence looms: will this signal the fall of the Islamic Republic, and what will rise from its ruins? Drawing on my own military experience, this analysis explores how a commando strike on Fordow could unfold. With my academic head on, it identifies the military, social, and psychological thresholds that could precipitate Iran’s collapse, as well as the options that might be available for the day after.

Subscribers in my Substack chat have spoken—you want this all in one go! This was a lot of work, and I would usually charge for it, but I think it’s important, so I’m going to leave it free to all. In return, all I ask is that you share it and urge people to subscribe. Fair deal?

Thanks for reading Andrew Fox’s Substack! This post is public so feel free to share it.

In a matter of days, Israel’s pre-emptive strikes have shattered Iran’s defensive shield. Iran’s air defence systems were swiftly eliminated, opening the skies to unimpeded Israeli air power. Simultaneously, precision strikes and covert operations decapitated key nodes of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) command, missile bases, nuclear facilities, and other military targets; too many to list here. The above-ground buildings at Natanz, once the centrepiece of Iran’s uranium enrichment programme, lie in ruins, their destruction confirmed by the UN atomic watchdog.

Several senior Iranian political and religious leaders have reportedly fled to safe havens in Russia: a dramatic signal of collapsing confidence. This exodus of the ruling elite, if accurate, delivers a decisive psychological blow. We are not there yet, but Khamenei himself fleeing would be comparable to the Shah of Iran boarding a plane in 1979 or Afghanistan’s president fleeing Kabul in 2021. It telegraphs to both regime loyalists and the public that the ship of state is sinking, potentially eroding any remaining will to resist.

Israel’s offensive seems aimed beyond just neutralising nuclear threats. It is “clearing the path” for Iranians to reclaim their freedom, as Prime Minister Netanyahu put it in a direct appeal to Iran’s people. In other words, regime change is an implicit objective of this campaign. The strikes have been calibrated to hit the regime’s instruments of repression and war (nuclear sites, IRGC bases, top generals) while minimising civilian casualties, in hopes that ordinary Iranians will not rally around the flag but instead turn on their weakened rulers.

So far, Iran’s retaliation has consisted of a barrage of missiles and drones, along with reported attempts at subversion within Israel itself. It has largely been thwarted. Israel’s multi-layered air defences (aided by US early warning and support) are performing effectively, mirroring past confrontations where massive Iranian missile salvoes were largely repelled by Israeli interceptors. Deprived of its most potent means of striking back and observing its military hierarchy in disarray, the regime in Tehran finds itself in an unprecedentedly fragile state.

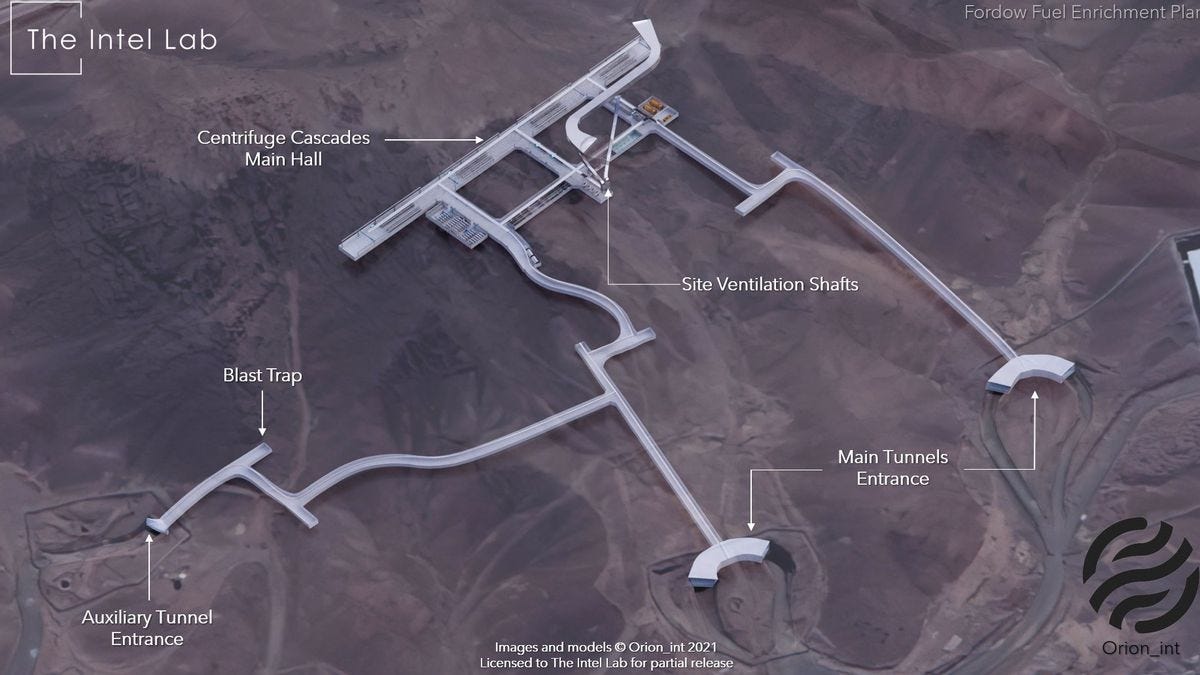

One looming issue remains unresolved: the Fordow uranium enrichment complex. Fordow is Iran’s most challenging nuclear site, buried half a mile deep under a mountain, and it has survived the initial onslaught intact. As long as Fordow remains operational, Iran’s regime keeps a dangerous ace up its sleeve. The facility houses advanced centrifuges enriching uranium to near-weapons-grade levels and could potentially expedite a crash nuclear weapons effort if the leadership feels cornered. In Israeli eyes, allowing Fordow to remain unscathed would be a grave mistake. It might even provoke Tehran to race for a bomb out of desperation or vengeance openly. For Israel’s campaign to genuinely eliminate the nuclear threat, Fordow must be neutralised one way or another.

Iran's Fordow nuclear facility. (X/@TheIntelLab)The Fordow Dilemma

Iran's Fordow nuclear facility. (X/@TheIntelLab)The Fordow DilemmaFordow presents a nightmarish target for military planners. It was explicitly designed to withstand the kind of airstrike that destroyed the Natanz facility. The complex is tunnelled into solid rock, beyond the reach of ordinary munitions. Only the US Air Force possesses bombs powerful enough (the 30,000-pound Massive Ordnance Penetrator (MOP) bunker-buster) and the heavy bombers to deliver them.

Israel, lacking these super-bunker-busters and strategic bombers, is unlikely to be able to pulverise Fordow by air alone. This is precisely why Israeli officials are urgently courting US involvement in the operation. If American B-2 bombers do not join the fray, Israel faces two unenviable options. (1) Attempting to jury-rig a solution with repeated air strikes on the same spot (to gradually bore into the mountain) or (2) sending in special forces on a high-risk mission to infiltrate and demolish the site from within.

A commando raid on Fordow would be a daring, last-resort gamble; something out of a Tom Clancy novel, yet not without precedent. In September 2024, Israel executed a similar operation in Syria. Codenamed “Operation Heavy Roads,” an elite Israeli special forces unit (Shaldag) clandestinely raided an underground Iranian-run missile factory near Masyaf, Syria. Over just two hours on the ground, the commandos neutralised guards, planted explosives throughout the facility, and reduced it to rubble without losing a single soldier.

This feat, once thought impossible, proved that a highly guarded underground site in a foreign country could indeed be infiltrated and destroyed by a well-executed special op. Fordow, however, is a far tougher nut to crack than the Syrian site. It lies on Iranian soil, at a far greater distance from Israel than Syria, protected by layers of security and burrowed deeper into the earth. A raid would likely require hundreds of special forces personnel. The team would need to breach reinforced tunnels or blast open access points, hold off or neutralise security forces inside, and emplace demolition charges on critical infrastructure (centrifuge halls, control systems, power supply), all before reinforcements arrive. The operation would rely on surprise, speed, and intelligence: real-time intelligence on Fordow’s layout and defences (possibly aided by insiders or years of Mossad surveillance) and deception to keep Iranian forces confused.

Such an endeavour would be extraordinarily perilous. A large assault force deep inside Iran could be encircled by the IRGC or trapped underground if anything goes awry. The commandos might need to fight their way out following the explosions or find an exfiltration route, perhaps via helicopter pickup at a pre-secured landing zone or an overland escape to a neighbouring country.

Despite these dangers, Israel may conclude that a commando strike is preferable to leaving Fordow untouched. The success of the Maysaf raid served as proof of concept that what was once dismissed as fantasy is now on the table. If Israel proceeds, a Fordow raid would likely involve multiple special forces units in a coordinated assault, supported by diversionary strikes and cyber-attacks to blind Iranian sensors. The world has not seen an operation of this complexity since perhaps the US raid that killed Osama bin Laden, and even that pales in comparison to the scale and stakes here. The elimination of Fordow might be the final, most dramatic chapter of this campaign, achieved either by US bunker-busters or the courage (and luck) of Israel’s most skilled commandos.

Thanks for reading Andrew Fox’s Substack! This post is public so feel free to share it.

When Does a Regime Collapse?Military pressure alone, irrespective of its intensity, does not automatically lead to regime collapse. The breaking point of the Iranian regime will depend on a convergence of social, military, and psychological triggers that ultimately tip the balance. Drawing from historical precedents and Iran’s unique context, we can split this into social, military, and psychological thresholds that must be met.

Mass civil unrest (social threshold). Widespread, sustained protests and chaos in the streets could signal that the regime’s authority is irreparably eroded. Iran has witnessed waves of mass protests before, but the difference now lies in the regime’s weakened coercive power. If news of the leadership’s flight emerges, ordinary Iranians may lose their fear and surge into the streets in vast numbers, sensing that the regime is on its last legs. A general strike, protesters overrunning government buildings, or large crowds gathering in Tehran’s Azadi Square to celebrate an anticipated “liberation” would exert enormous pressure on what remains of the security forces. Unlike past uprisings, protesters would now carry the morale boost of having seen the once-mighty IRGC humbled by Israeli strikes. Exiled opposition figures are openly encouraging civil resistance. Reza Pahlavi, the ex-crown prince, urged Iranians and even security personnel to seize this moment, declaring, “The regime is weak and divided… Iran is yours to reclaim”. If the populace answers that call en masse, sheer people power could overwhelm the regime’s remaining loyalists.

Fracturing of Security Forces (military threshold). The Iranian regime’s survival has long hinged on the loyalty of its armed organs, such as the IRGC, the Basij militia, and the regular army. A collapse becomes likely if these forces fracture or stand down. We may see signs like mid-level commanders refusing orders to fire on crowds, garrisons surrendering or deserting, or even firefights between factions (e.g. IRGC hardliners vs Army units) as the chain of command breaks down. The decapitation strikes that killed or incapacitated many top generals and IRGC commanders are crucial here. They removed a vital component of the regime's stability, potentially throwing the security establishment into confusion and leaderless disarray. With communications disrupted and commanders dead, frontline units might act on their instincts. The military rank-and-file, who are themselves Iranians with families suffering under the regime, could decide not to die for a lost cause. Even pockets of the IRGC, especially those deployed outside their home regions, might choose to abandon posts or negotiate with local communities. A pivotal moment would be if a major military unit or division openly switches sides to support the people, as happened in some instances of the 1979 revolution. Once security forces cease to function as a united repressive tool, the regime’s physical power collapses.

Psychological shock at the top (psychological threshold). Authoritarian regimes often project an aura of invincibility. Shattering that illusion can trigger a rapid unravelling. In Iran’s case, the sight (or rumour) of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei and his inner circle fleeing by plane to a foreign haven could be that shock. If the Supreme Leader is perceived to have given up or gone into hiding, it is game over for regime cohesion. Mid-level officials and clerics would begin defecting or disappearing, anticipating the regime’s fall. The remaining loyalists might resort to desperate, vicious measures, but their morale would be in free fall. Each additional blow, be it the fall of a major city to protesters or a live broadcast of a prominent ayatollah or Revolutionary Guard general announcing his resignation, would reinforce the collective sense that “this is the end.” We saw similar dynamics in other collapses: once fear shifts sides, the regime that once terrified everyone suddenly finds itself the one frightened of its people. As we saw last year in Syria, psychological tipping points can be abrupt. One day, a dictatorship seems securely entrenched; the next day it is melting away like ice in the sun.

Other factors could also accelerate the collapse. Information and communication will play a significant role. The regime has attempted to shut down the internet to prevent coordination, but reports suggest systems like Starlink are circumventing the blackout. This means that news of regime weakness and battlefield defeats spreads quickly, fueling the cycle of discontent. Meanwhile, economic paralysis (with banks closed and markets in a state of panic) and the breakdown of basic services (power outages resulting from strikes on infrastructure) contribute to a sense of impending chaos, convincing many Iranians that change is both inevitable and urgent.

Taken together, these social, military, and psychological triggers feed off one another. We may not pinpoint the exact moment of no return until we have the benefit of hindsight, but it could arrive soon. Perhaps it will be when a protester’s video goes viral, showing IRGC troops laying down their arms and joining the crowd, or when Friday prayers in a major city evolve into open defiance of the mullahs. When that moment arrives, the Islamic Republic’s 46-year reign could unravel with astonishing speed, ending not with a negotiated handover but with a sudden vacuum at the centre of power.

Andrew Fox’s Substack is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

The Day AfterWhat might Iran look like immediately after the regime falls? This is the great unknown hanging over the current crisis. History offers both hopeful examples and dire warnings. Optimists might recall how relatively smoothly Eastern European regimes fell in 1989 or how Portugal’s regime collapsed in 1974 without descending into anarchy. However, the recent past of the Middle East, including Syria’s civil war, Libya’s post-Gaddafi chaos, and Iraq’s violent power vacuum, urges caution. Several broad scenarios are possible for a post-regime Iran, each with very different implications.

Scenario 1: fragmentation and civil conflictThis is one nightmare outcome. Iran could fracture into warring fiefdoms and sectarian strife, akin to Syria or Libya. If the central authority were to collapse suddenly, Iran’s diverse society might split along regional, ethnic, or ideological lines. The IRGC or its factions could retreat to strongholds and effectively become warlords. Different parts of the country (the Kurdish northwest, Balochi southeast, the Persian heartland, and Azeri north) might witness the emergence of local power brokers or separatist groups, each claiming autonomy. Outside powers could exacerbate tensions by fuelling proxies. For example, Turkey might seek influence in Turkic/Azeri regions, while Saudi Arabia could quietly support anti-IRGC Sunni groups, etc.

In this scenario, a protracted war for power and chaos unfolds on Iranian soil. The humanitarian toll would be immense, and Iran’s vast arsenal (including missiles and the remnants of the nuclear programme) could fall into multiple hands. A civil war could also spill across borders, sending refugees into Turkey, Azerbaijan, Iraq, and beyond. No one desires this, not even Iran’s adversaries, because a failed state of 85 million people in such a strategic location would be catastrophic.

Scenario 2: hardliner military juntaAnother, even worse, possibility is that the clerical leadership’s fall paves the way for an even harder-line authoritarian regime; essentially a military junta led by the IRGC. In this case, the Revolutionary Guard, or a coalition of the most ruthless elements within it, may suppress rivals and seize complete control of what remains of the state. Imagine martial law under a charismatic IRGC general or a “council” of hardliners who deem the mullahs too indecisive.

Such a regime could be much more militarised and potentially more dangerous. Free from the pretence of clerical rule, an IRGC junta might be unabashed in pursuing a nuclear weapon as swiftly as possible, viewing it as the guarantor of their survival. Those who insist nothing could be worse than the current theocracy may be naïve; recent history tells us it can always be worse. For Israel and the world, an embittered military dictatorship in Tehran, particularly one born from the ashes of war, could be just as hostile as the old regime, if not more so. It might impose internal crackdowns even more severely and double down on alliances with countries like Russia or China for survival. Essentially, the faces at the top would change, but the repression and regional aggression could continue in a new form.

Scenario 3: transitional council and hopeful reformIn a more optimistic scenario, responsible elements within Iran and the opposition could step into the vacuum to stabilise the country. Perhaps moderate figures from the regular Army, some reformist politicians, and exile leaders could form a provisional “national salvation council.” This interim leadership might restore order in major cities, call off any further fighting, and initiate talks for a new political system (be it a republic or even a constitutional monarchy restoration). They would almost certainly seek emergency economic aid and diplomatic recognition.

The Iranian diaspora, long fractured but united in its desire for an end to the Islamic Republic, would likely play a key role in providing technocrats and funding to rebuild. Under this scenario, Iran’s new leaders would distance themselves from the old regime’s policies. They would move to cease uranium enrichment and invite the International Atomic Energy Agency to inventory nuclear materials. The nuclear weapons programme would be halted in exchange for sanctions relief and reconstruction support.

Regionally, a post-Islamist Iran might stop funding militias like Hezbollah and Hamas, seeking normal relations with neighbours. This is the “best case” vision: Iran emerging from turmoil relatively quickly, with a chance to build a freer society. It is not guaranteed. Such a smooth transition would require unity among very disparate factions and likely some form of international peacekeeping or monitoring to prevent score-settling. However, it is not impossible, especially if most Iranians, exhausted by decades of repression and the trauma of war, embrace a unifying call and focus on rebuilding their nation.

Scenario 4: partial continuity (regime fragments strike a deal)

Another possibility is a semi-managed collapse. Perhaps elements of the regime, sensing the writing on the wall, negotiate a handover of power to a temporary authority rather than fight to the bitter end. For example, if some senior Revolutionary Guard officers and politicians oust the hardline core (or if Khamenei dies or flees and there is no clear successor), they might reach out to opposition figures to form a transitional government. In effect, part of the old elite could try to save the country (and themselves) by facilitating a change.

This scenario would align with scenario 3 in terms of outcomes. A new, more moderate government would arise from an internal coup or pact. It might preserve more of the state’s institutions intact (preventing total collapse). The risk here is that it could also maintain some unsavoury elements of the old regime in power, possibly disappointing protesters who wanted a clean break. Nonetheless, it could avert civil war. Under such continuity, Iran’s territorial integrity is upheld, and the new government would likely still abandon the nuclear weapons quest under international supervision (both to get sanctions lifted and because many of those pushing for change internally know the nuclear path brought ruin).

Final ThoughtsIn all the above scenarios, Iran’s nuclear programme and regional posture will be central concerns. A collapsed or transitioning Iran would immediately face international demands to secure nuclear materials. One can expect US and Israeli intelligence (and possibly special units) to move swiftly to account for enriched uranium and prevent any covert “last resort” use or transfer of fissile material by die-hard factions. If chaos reigns, securing Fordow and other nuclear sites might even require an international task force. There would be the grim prospect of foreign troops in Iran, which could stir nationalist resentment.

Conversely, a cooperative new Iranian authority would likely invite the IAEA and perhaps UN-mandated teams to help dismantle the weapons-related parts of the programme. Regional stability would, in the short term, be shaky. Iran’s proxies and allies (Hezbollah in Lebanon, militias in Iraq and Syria, the Houthis in Yemen) would suddenly lose their patron and could either wither or act unpredictably. Some might try to go it alone (for example, Hezbollah could lash out or attempt to survive via other sponsors). In contrast, others might lay low or enter political processes if conflicts wind down without Iranian funding. Israel and the Gulf Arab states would certainly celebrate the end of the Islamic Republic, but they would remain wary until a clear picture of the new order emerges. If Israel succeeds in removing Iran’s leadership, there is no guarantee the successor would not be even harderline.

For the United States and global powers, a post-collapse Iran presents a strategic dilemma. On one hand, the elimination of a hostile regime and the hopeful end of Iran’s nuclear ambitions would represent a significant victory for non-proliferation and regional peace. On the other hand, the international community could face a substantial stabilisation and rebuilding effort. Consider post-2003 Iraq, but on an even larger scale. Mistakes made then, such as disbanding the army overnight or allowing a security vacuum, would serve as painful lessons when approaching Iran’s situation. There may be calls for a UN peacekeeping mission to maintain order in key cities or safeguard minority communities during the transition. Major humanitarian aid and economic packages would be necessary to address Iran’s damaged economy and infrastructure, especially as the conflict has devastated refineries, power plants, and so on.

In a best-case scenario, Iran could re-emerge in a few years as a nation at peace with its people and neighbours. No longer isolated, no longer pursuing nuclear weapons, and focused on prosperity. This would transform the Middle East. Imagine Iran’s vast human and economic potential redirected from proxy wars to development and trade. Arab states might eagerly court a friendly Iran, and even the Israel-Iran hostility could fade if a new Tehran renounces calls for Israel’s destruction. However, we must remain clear-eyed. Such positive change would require deft management of the immediate aftermath. The transition could be as perilous as the conflict itself. As TIME magazine noted, “things may get much worse before they get even worse” in this region. That tongue-in-cheek phrasing reflects the volatility of the situation. A collapsing regime can unleash forces that are hard to control.

The collapse of Iran’s Islamic Republic, once almost unthinkable, is now a distinct possibility amid the onslaught of war and internal discontent. Here, I have sketched how it might occur, through a mix of military blows, popular uprisings, and psychological breaking points; and what might follow, ranging from hopeful renewal to chaotic strife. From a military analyst’s perspective, while ending a brutal regime could open the door to a better future for Iran and the world, it also opens Pandora’s Box. Decision-makers in Jerusalem, Washington, and beyond are surely considering these scenarios as they weigh each next step.

The coming days will test whether Iran’s 85 million people can seize this tumultuous moment to build something new, or whether the aftermath of regime collapse becomes a new tragedy of its own. One thing is sure: the end of the Ayatollahs’ rule would mark a historic turning point, and its full consequences, for the nuclear programme and regional stability, would be felt for years to come. The world can only watch, hope, and, where possible, help steer events toward the most peaceful outcome.

Andrew Fox’s Substack is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

This will be the topic of discussion for my weekly podcast with Shana Meyerson, “A Paratrooper and a Yogi Walk Into A Bar”, so please do subscribe in advance! Find it in the podcast section of my Substack page, or: