Two Sixties Rock Songs That Celebrate Capitalism’s Greatest Creation

Perhaps the greatest achievement of capitalism is the creation of the phenomenon of leisure, which has become the object of cultural recognition and celebration in modern capitalist countries.

For millennia prior to the dawn of the Industrial Revolution in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries in Europe, the vast majority of men, women, and children toiled from dusk to dawn and beyond just to keep body and soul together. Leisure as we know it today did not exist except among kings and lords of the manor and their retainers. For ordinary people there were only brief respites from their labor on Sundays and holidays, during which they fulfilled their religious obligations. It was the enormous increase in the productivity of labor unleashed by the capitalist mode of production that bestowed meaningful “leisure time” on the masses, which has been celebrated in cultural media since the end of World War II. Because rock music is one of my favorite cultural media, I will analyze two classic songs recorded in the mid-1960s that recognize the close relationship between capitalism and leisure. Before I do so, however, I would like to say a word about the economics of leisure.

We tend to take leisure for granted because its production is instantaneous and its consumption is intermingled so closely with the consumption of the services of other goods in the form of “leisure activities.” Leisure is time that we choose to spend not working and therefore excludes the resting time physiologically required to restore the energy we need to function as acting beings. Working out at a health club, entertaining friends with a dinner party, and religious worship all require leisure as a complementary good. However, leisure is a good that cannot be bought and sold on the market. Like romantic love, friendship, and good reputation, it is also a (non-exchangeable) consumer goods because it is scarce and contributes directly to satisfying human wants and desires. Furthermore, just as spending money on exchangeable goods is costly, spending time on leisure activities also involves a cost. The cost of leisure is not directly monetary but rather the forgone opportunity to earn money from selling one’s labor services on the market to a business firm or laboring in one’s own business. For example, if a home care nurse earns $40 per hour and can vary her time worked in four-hour shifts, then it “costs” her $160 (before taxes) in forgone wages to “purchase” four additional hours of leisure by reducing her working hours from 36 to 32 hours per week.

Although leisure can be “produced” only by the person who intends to consume it and cannot be purchased from other people, the demand for leisure is subject to the same law of economics that governs the demand for exchangeable goods, namely, the “law of marginal utility.” This law states that as the supply of a good an individual possesses increases, the personal or “subjective” value he attaches to the good declines relative to the subjective values of other goods. Applied to the case we are about to consider, this law implies that as workers’ wages increase, enabling them to purchase greater quantities of consumer goods on the market, an hour of leisure tends to become relatively more valuable. This increases their willingness to “purchase” additional hours of leisure by reducing their hours worked and forgoing the wages they could have earned.

Since the dawn of the industrial revolution, which was ushered in by the ideology and system of capitalism, the astounding increase in saving and investment in capital goods and improvements in technology has driven labor productivity and real wages sharply upward. For example, as the graph below indicates, average weekly real wages—the amount of goods and services an average laborer could purchase with his or her weekly earnings—in the United Kingdom increased almost 20 times from 1800 to 2014. (An interactive version of the graph is here.)

In the United States, where the industrial revolution started much later than in Great Britain, the graph below shows that real average annual earnings of non-farm employees rose by 30 percent from 1865 to 1890. By 1988, an alternative index of real average hourly earnings in manufacturing in the United States was 55 times greater than it was in 1890. (An explanation and interactive version of the following graph is here.)

As real wages continued their dizzying rise, driven by rapidly increasing capital investment and industrialization, they were spent on acquiring the expanding supplies of consumer’s goods cascading onto markets. As noted, the subjective value of these goods tended to decline on laborers’ personal value scales relative to the value of leisure. To prevent an imbalance or “disequilibrium” of value between leisure and exchangeable goods from developing, laborers chose to progressively increase the proportion of their wages devoted to the purchase of leisure by reducing labor hours exchanged for wages on the market. In the example of the home care nurse above, the equilibrium of value between leisure and other consumer goods is restored when the subjective value of an additional four hours of leisure roughly equals—or more exactly, just exceeds—the value of $160 dollars of wages sacrificed or any collection of goods she could have purchased with that sum of money. If the nurse were to trade off any more wages for leisure, then her welfare would be reduced because the value of the added hours of leisure would drop below the additional wages and consumers goods she would have to forgo.

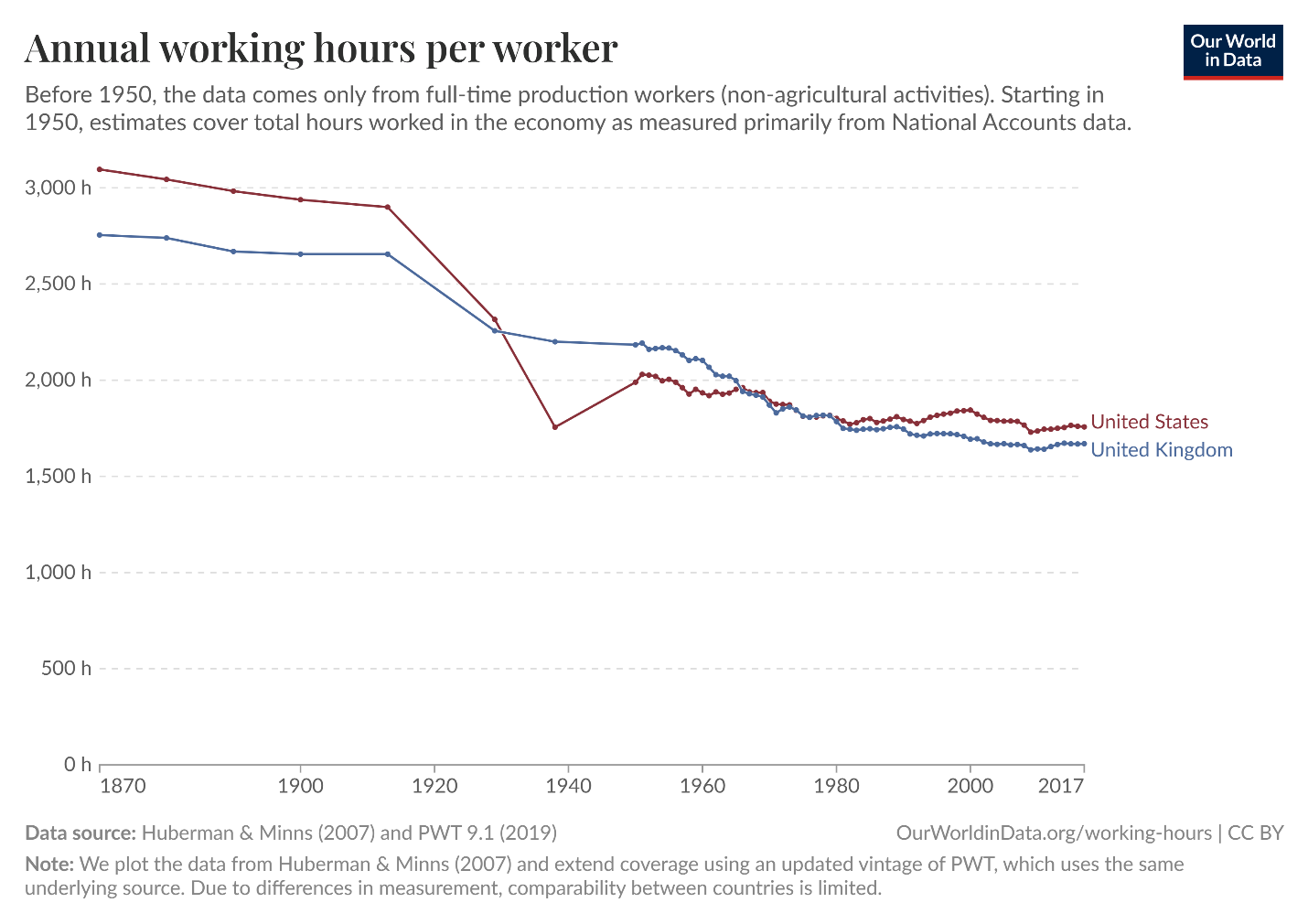

Let us look at how this adjustment process of leisure to the rise in real wages has played out historically. As the graph below shows, in the United States in 1870, production workers averaged 3,096 hours of labor per year. By 2017, the average annual working hours per worker had fallen to 1,755, a decline of over 43 percent. For the United Kingdom over the same period, these figures were 2,755 hours and 1,670 hours, respectively, a decline of nearly 40 percent in annual working hours. For the United States, almost three-quarters, or 31 percentage points of the 43 percentage-point decline in annual working hours during nearly a century-and-a-half, occurred during the 38 years from 1913 through 1950. In the United Kingdom, during the same 18-year period, annual working hours fell by nearly one-half of their total decline from1870 through 2017. (An explanation and interactive version of the following graph is here.)

By the advent of the 1960s, the notions of “the weekend” and “quitting time” or the “end of the workday” began to be portrayed in the news and cultural media as a cause and opportunity for celebration. Two rock songs released in the mid-1960s vividly illustrate this phenomenon. The first is titled “Five O’Clock World” (sometimes written “5 O’Clock World”) and was recorded by the American pop group The Vogues. The record, which can be heard here, peaked at number 4 on the Billboard’s Hot 100 chart in January 1966.

The lyrics of the first verse of the song laments the physical and mental anguish caused by the workday:

Up every morning just to keep a job

I gotta fight my way through the hustling mob

Sounds of the city pounding in my brain

While another day goes down the drain

The first chorus quickly transitions to an account of the worker’s eager anticipation of the end of the workday when he will emerge as literally a new person, stepping out of his work clothes and into a radically different world of leisure and consumption activities.

But it’s a five o’clock world when the whistle blows

No-one owns a piece of my time

And there’s a five o’clock me inside my clothes

Thinking that the world looks fine, yeah

The second verse transports us back to the workday world:

Trading my time for the pay I get

Living on money that I ain’t made yet

Gotta keep goin’ gotta make my way

But I live for the end of the day

The foregoing lyric refers to two capitalist institutions that helped make possible the enormous increase in labor productivity and real wages. First, there is the wages system itself, wherein workers voluntarily “trade their time” for money payment. The variation in wages rates among the different lines of production indicates to workers where their value to consumers and their own compensation are highest, while permitting them to choose the job that best suits them considering their personal preferences for particular working conditions. Then, there are the credit markets that enable workers with prospects of increasing incomes to borrow money in exchange for an interest premium and to enjoy a standard of living in the present that is higher than their current wages would permit. In terms of the lyrics, they are “living on money they ain’t made yet.” More importantly, capital markets, which include credit markets, prompt entrepreneurs to invest the continually increasing flow of scarce savings and capital in those production processes that increase workers’ productivity and raise their real wages. And it is precisely the astonishing increase in real wages under capitalism that has created “the five o’clock world” and allowed workers, in the words of the last line of the verse, “to live for the end of the day”—rather than face the grim prospect of returning home taking some nourishment and slumping into bed utterly exhausted.

In creating the world of leisure, capitalism also gave rise to the flourishing of family life and romantic love, for most people highly-valued goods whose consumption requires leisure. Fittingly, the song ends with a celebration of leisure, “the five o’clock world,” as an indispensable means for attaining these goods:

‘Cause it’s a five o’clock world when the whistle blows

No-one owns a piece of my time

And there’s a long-haired girl who waits, I know

To ease my troubled mind, yeah! . . .

In my five o’clock world she waits for me

Nothing else matters at all

‘Cause every time my baby smiles at me

I know that it’s all worthwhile, yeah

The second song that pertains to our theme is “Friday on My Mind.” Performed by the Australian rock band The Easybeats, the record, which can be heard here, was released in 1966 and reached number 16 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart in May 1967 in the United States. It was a worldwide hit and, in 2001, was voted “Best Australian Song” of all time by APRA (Australasian Performing Right Association).

The lyrics begin with the worker’s subjective reaction to the drudgery of the work week and reveal his laser-like focus on the arrival of the weekend and the variations in his mood as it approaches:

Monday mornin’ feels so bad

Everybody seems to nag me

Comin’ Tuesday I feel better

Even my old man looks good

Wednesday just don’t go

Thursday goes too slow

I’ve got Friday on my mind

The chorus that follows celebrates the arrival of Friday evening and the worker’s impending physical and emotional release from the work week. It also alludes to two capitalist institutions that facilitate and promote the consumption of the leisure activities the worker longs for: the city and money (“bread”).

Gonna have fun in the city

Be with my girl, she’s so pretty . . .

Tonight I’ll spend my bread, tonight

I’ll lose my head, tonight

I’ve got to get to night

Monday I’ll have Friday on my mind

In the pre-industrial world, “the city” meant the capital city where the king and his family and court were ensconced. The capital was built and subsisted on the wealth that was expropriated by the ruling class through taxation of the producers—the craftsmen, artisans, and farmers inhabiting the towns and rural communities. It also served as the playground for the monarch and his royal cronies where they frolicked and cavorted, disgorging their ill-gotten gains on their leisure pursuits. Capitalism transformed cities from pleasure preserves for the politically powerful and privileged to centers of industry, finance, commerce, and entertainment where workers, capitalists, and entrepreneurs produced and then consumed the ever-increasing fruits of their efforts. The expansion and multiplication of cities under capitalism enabled and were driven by the expansion of the money economy until it encompassed all households and businesses. Money became the universal medium of exchange and money wages the “open sesame” for the masses to access the consumer goods—including things formerly considered “luxuries”—that gushed forth from capitalist mass production while indulging in the diversions and pleasures of leisure previously reserved to the ruling elites.

The second verse of the song again bemoans the tedium of the work week but suggests a prospective escape from traditional employment—but not from productive effort—via another capitalist institution:

Do the five day grind once more

I know of nothin’ else that bugs me

More than workin’ for the rich man

Hey! I’ll change that scene one day

Today I might be mad, tomorrow I’ll be glad

‘Cause I’ll have Friday on my mind

The “rich man” who irks and maddens the employee is, of course, the entrepreneur. In vowing to “change that scene one day,” the worker is declaring his intention to go to work for himself, to become an upstart entrepreneur, to out-compete the existing “rich men.” The song concludes with a repeat of the chorus with the worker keenly anticipating the imminent arrival of Friday evening mere hours away where await the delights and gratifications of the weekend.

Gonna have fun in the city

Be with my girl, she’s so pretty . . . .

Tonight I’ll spend my bread, tonight

I’ll lose my head, tonight

I’ve got to get to night

Monday I’ll have Friday on my mind