Why immigration research is probably biased

Public opinion surveys across Western countries consistently show that majorities prefer lower immigration levels. Yet, academic studies on immigration—particularly for welfare states and social cohesion—often report neutral or positive effects, downplaying public concerns.

Researchers explain this mismatch through their alleged superior knowledge. Ordinary people (at least the ones I know) put forth a different explanation: immigration researchers are people who have always been ideologically pro-immigration, and their ideology either clouds their judgment or makes them tweak evidence to arrive at their ideologically desired conclusion. Here, I discuss evidence on the latter explanation.

Research on how researchers do researchThe best evidence to address this hypothesis comes from a many-analysts projects by Breznau, Rinke, Wuttke, and collaborators (2022). They recruited independent research teams, whose decisions and results we are interested in, to test the same hypothesis: “greater immigration reduces support for social policies among the public”.

This hypothesis traces back to influential work by Alesina and Glaeser (2004), who argued that ethnic homogeneity enables generous welfare systems because taxpayers are relatively more ready to pay for welfare recipients from their own ethnicity. This conclusion is a bitter pill to swallow for people on the political left since they desire both ethnic heterogeneity and a generous welfare system. If these two goals conflict with each other, it’s bad news for the left.

Over the decades, studies have yielded conflicting empirical results on this question. Now, Breznau, Rinke, and Wuttke (2022) study how other researchers examine this question, given the same starting conditions.

They recruited researchers through academic networks, social media, and professional associations across the social sciences and ended up with a working sample of 158 researchers in 71 teams. Nearly half came from sociology, about a quarter from political science, and the remainder from economics, communication, or more interdisciplinary and methods-oriented backgrounds. Over 80 percent had taught data analysis, and 70 percent had previously published on immigration or welfare states.

Before any modelling, participants reported their personal stance on immigration policy (“Do you think that, in your current country of residence, laws on immigration of foreigners should be relaxed or made tougher?”; 7-point scale).

All teams then received the same data and the same task. The data combined public opinion surveys from the International Social Survey Program with official statistics on immigration. The International Social Survey Program includes six questions measuring support for government responsibility in areas like pensions, unemployment, and health care (e.g., “Do you think it should or should not be the government’s responsibility to provide health care for the sick”; 4-point scale). These exact questions had already been used in one of the most cited papers on the topic, by Brady and Finnigan, which participants were asked to replicate as a starting point. Researchers were also provided with two measures for immigration per point in time: the foreign-born population as a share of the total population (“stock”), and changes in that share over time (“flow”). These indicators were drawn from the World Bank, the UN, and the OECD. In total, the dataset covered up to 31 mostly high-income countries across as many as five survey waves between 1985 and 2016.

To eliminate career incentives that might push researchers toward particular results, all participating teams were guaranteed authorship on the final paper regardless of what they found. Teams were simply instructed to estimate the effect of immigration on welfare support.

The many choices a researcher can makeA hugely underappreciated fact is that researchers have to make many difficult decisions when analysing data. In the Breznau, Rinke, and Wuttke (2022) study, these choices also translated into substantial heterogeneity in what exactly teams did. Some estimated multilevel models with random effects at multiple levels; others relied on simpler specifications and instead clustered standard errors at the country, wave, or country–wave level. Still others ignored hierarchical structure altogether. Estimation strategies also varied widely: while many relied on ordinary least squares, others used maximum likelihood estimators or Bayesian approaches. Data handling choices compounded this variation. Teams differed in which ISSP questions they treated as the main dependent variable, how they scaled welfare support (continuous, ordinal, dichotomous, or multinomial), which immigration measure they emphasized (stock versus flow), and how they subsetted the data across countries and waves. None of these choices is exotic or illegitimate; they are all defensible, giving researchers much discretion.

All of these choices resulted in 1,261 submitted models; no two were identical. Notably, this heterogeneity arose even though the hypothesis and data were the same! Think how much freedom researchers have when they are allowed to choose the hypothesis and the data.

After submitting their results—but before seeing anyone else’s—each team was shown brief descriptions of several other teams’ models and asked to rank them according to how well they tested the hypothesis. Aggregating these peer evaluations allowed the organizers to construct quality rankings of models, independent of their results.

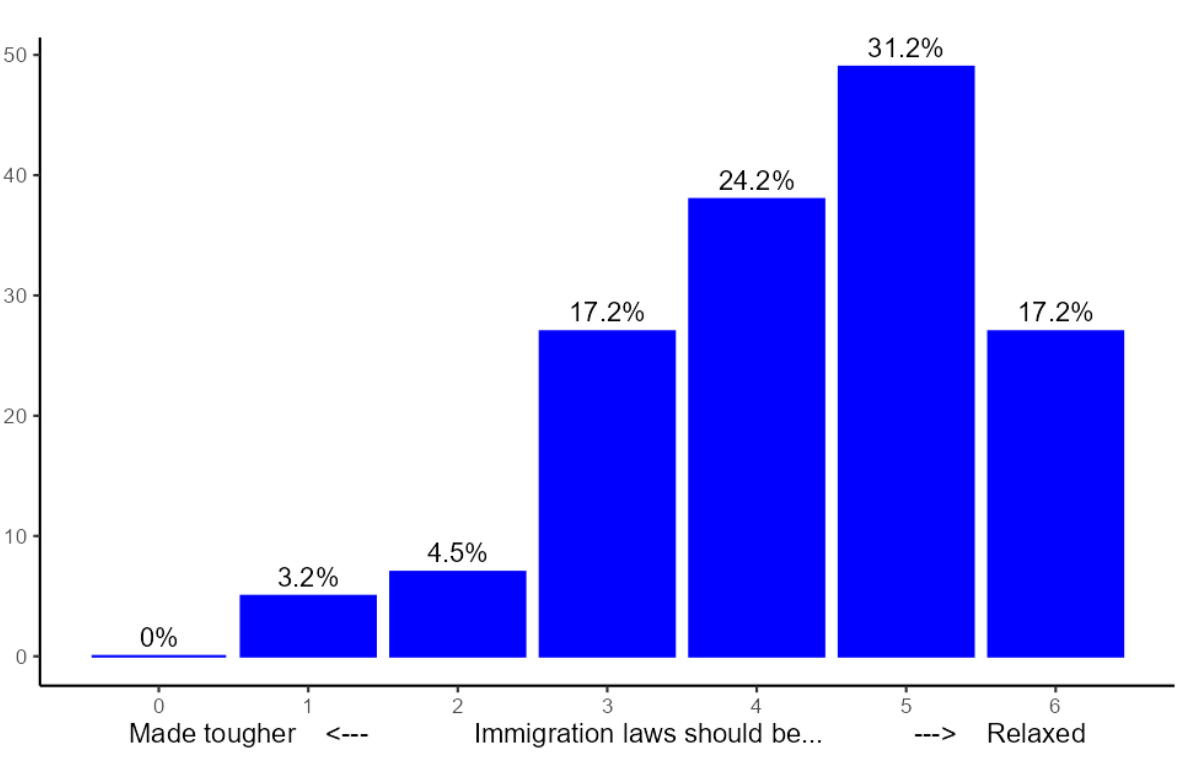

ResultsImmigration researchers are overwhelmingly pro-immigration Figure 1: Immigration attitudes of immigration researchers. Taken from this paper.

Figure 1: Immigration attitudes of immigration researchers. Taken from this paper.Figure 1 visualizes the personal immigration attitudes of the researchers. More than 72% think that immigration laws should be relaxed. Another 17% think immigration laws should neither be relaxed nor made tougher, and less than 8% think they should be made tougher.

These attitudes stand in stark contrast to comparable responses of the general population, where large majorities think that laws should be made tougher. In particular, not a single researcher participant chose the most right-wing option, which is often one of the most frequently chosen in public opinion surveys. It is also notable that the immigration attitudes of researchers resemble those of politicians, who are also much more pro-immigration than the general public.

Of course, Figure 1 is based on a small subset of all immigration researchers. However, working in that field, I am quite sure that this result generalizes: immigration researchers and the general population want to shift immigration policymaking in opposite directions.

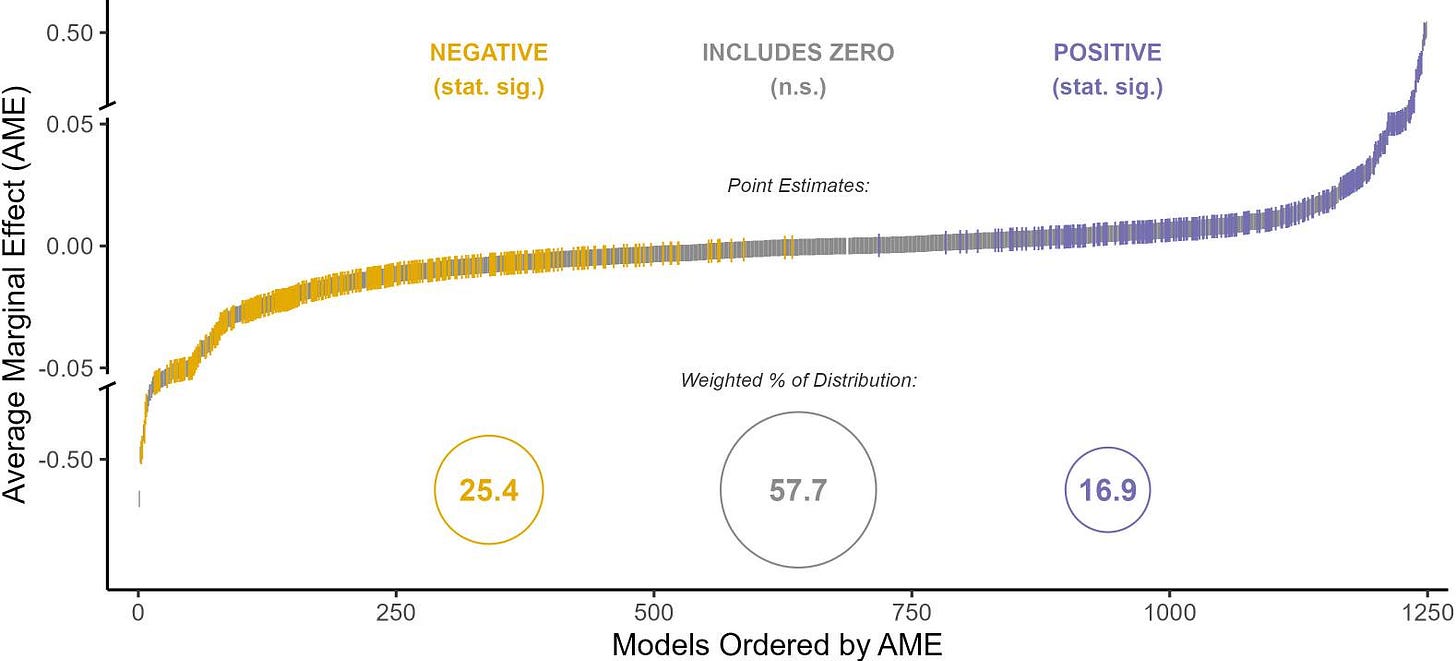

Immigration researchers obtain opposite estimates from the same data Figure 2: Coefficients immigration researchers estimated using the same data for the same research question. Taken from here.

Figure 2: Coefficients immigration researchers estimated using the same data for the same research question. Taken from here.Figure 2 depicts the cumulative distribution function of estimated coefficients. There are more coefficients than research teams because teams reported several models. Even though all teams tested the same hypothesis using the same data, “no two teams arrived at the same set of numerical results. More strikingly, there is not even broad agreement on whether the effect is negative (immigration erodes welfare support), positive (immigration increases it), or non-existent. Large shares of research teams find negative, positive, and no significant effect, respectively.

Overall, 13.5% of all teams concluded that the hypothesis was not testable given these data. 60.7% concluded that the hypothesis should be rejected, and 28.5% found that the hypothesis was supported. Thus, most teams concluded that immigration does not reduce support for social policies among the public, which is the result that someone with a left-wing ideology wants to find.

These different findings resulted, of course, from different analysis choices. Notably, there are not a few choices that account for most of the variation. The authors note that “more than 95% of the total variance in numerical results remains unexplained even after qualitative coding of all identifiable decisions in each team’s workflow.” Hence, each choice, like adding a control variable, makes a small difference, and due to their sheer number, effects add up.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

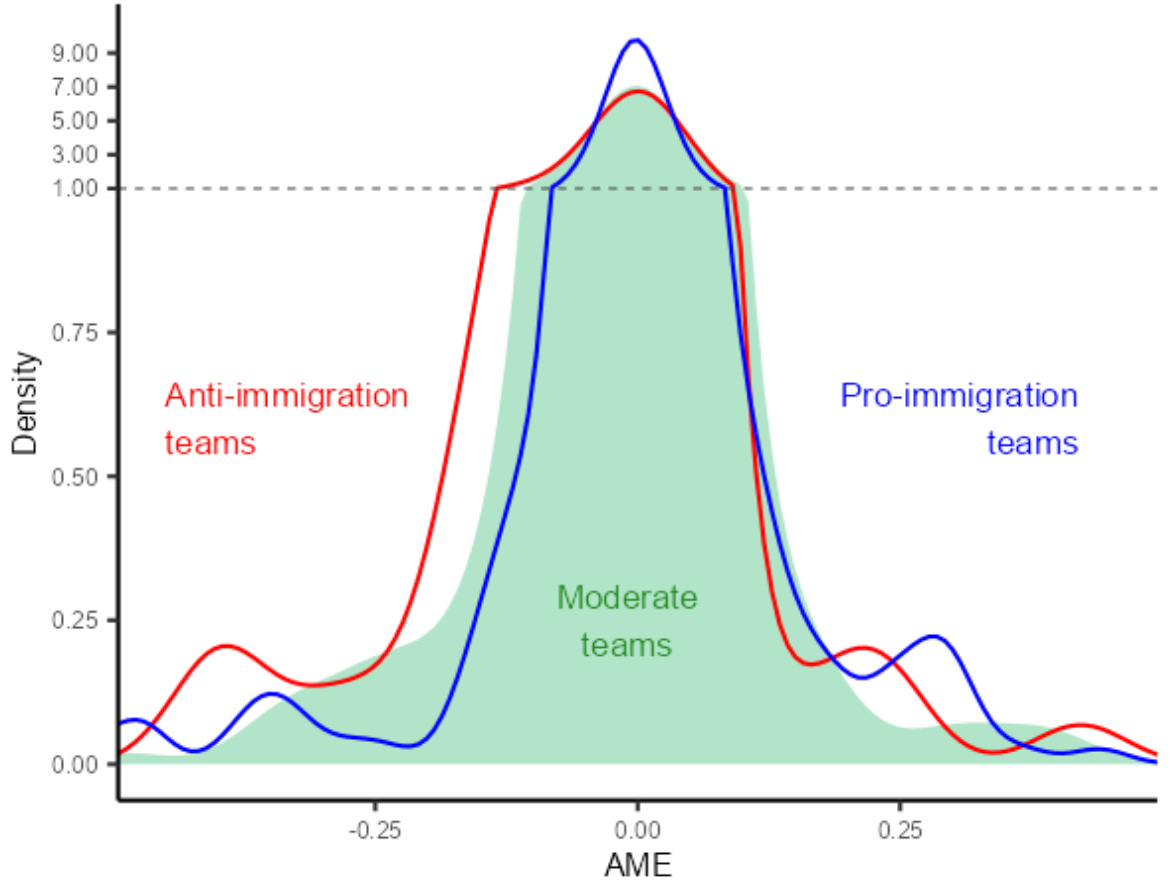

Researchers found what they wanted to find Figure 3: Distribution of effects estimated by research teams by immigration attitude

Figure 3: Distribution of effects estimated by research teams by immigration attitudeIt is certainly not great for a discipline if, given the same data, 61% of researchers think a hypothesis should be rejected while 29% see support for it. The sceptical reader may wonder how this literature can teach us anything if its members cannot even agree among themselves. However, this finding does not necessarily indicate a bias.

The more worrying result comes from a follow-up study (Borjas and Breznau 2024). They examine whether the researchers’ prior immigration attitudes explain their findings. To that end, Borjas and Breznau define a pro-immigration team as one where more than half the members chose one of the two most extreme pro-immigration options (5 or 6, see Figure 1). This classifies 44% of all teams as pro-immigration. Given the rarity of anti-immigration attitudes among participants, Borjas and Breznau classify teams with at least one member responding with an attitude of “1” or a “2” as anti-immigration (because no one chose the most extreme anti-immigration option; 0). This definition classifies roughly 13% as anti-immigration. The remaining 44% were classified as “moderate.” These different findings resulted, of course, from different analysis choices. Notably, there are not a few choices that account for most of the variation. The authors note that “more than 95% of the total variance in numerical results remains unexplained even after qualitative coding of all identifiable decisions in each team’s workflow.” Hence, each choice, like adding a control variable, makes a small difference, and due to their sheer number, effects add up, leading to very different results.

Figure 3 visualizes the distribution of the estimated effect by team type. The average effect estimated by anti-immigration teams was negative (i.e., immigration erodes pro-welfare attitudes), close to zero for moderate teams, and positive for pro-immigration teams. These differences were to a notable extent driven by a higher likelihood of anti- and pro-teams to obtain extremely large estimates. This association between researcher ideology and their findings is significant and remains robust after controlling for academic discipline, statistical skills, research experience, and many other factors.

How large are these differences? Borjas and Breznau’s most rigorous analysis implies that moving from one ideological extreme to the other shifts a team’s estimate from roughly the 16th percentile of the (control-adjusted) effect distribution to the 63rd percentile. Looking at Figure 2 (which shows a slightly different distribution), that means going from the region where effects are largely negative and statistically significant to the region where they are mainly positive and significant.

As Figure 3 reveals, there is still substantial heterogeneity with each team and, e.g., some pro-immigration teams find negative effects. Hence, the importance of researchers’ attitudes should not be overstated. However, these three distributions do imply qualitatively different narratives of how the world works and therefore also have qualitatively different policy implications. Imagine a world in which the entire research community consisted mostly of anti-immigration scholars (roughly mirroring the general public in Western countries). If we pooled all their estimates, the literature would conclude that immigration erodes support for the welfare state. If, instead, all researchers were in favour of the current immigration policy, the average effect would hover around zero, and we would conclude that immigration has no meaningful impact on welfare attitudes. But in reality, most immigration researchers lean strongly pro-immigration. And in that world, the aggregated literature tends to produce estimates suggesting that immigration is good for social cohesion and welfare support.

So far, the evidence is well in line with the true effect simply being positive, such that most teams discover it. However, Borjas and Breznau found that extreme priors (pro or anti) correlated with lower methodological quality, as assessed blindly by independent referees. Moderates, those with a prior of 4, made the most valid model choice and are therefore most likely to obtain the correct estimate. Hence, pro-immigration researchers in particular appear to have reached their conclusion by making less valid choices in their analysis, thereby reaching a biased conclusion. If anti- and pro-immigration researchers were similarly frequent, such a bias may cancel out. However, pro-immigration researchers outnumber anti-immigration researchers and moderates, whose analyses are most reliable combined. The results is a literature containing mainly a small share of moderates doing rigorous research and a larger group of ideologically motivated pro-immigration “researchers” who torture the data until they “find” a pro-immigration message.

Beyond model choiceAll of the heterogeneity and potential bias discussed above just resulted from researchers choosing which subset of data to analyse and which exact regression models to employ. Imagine how much more heterogeneity and room for biases arise if researchers can choose the data, whether and how to design an experiment, whether to publish results or not, and so on.

Maybe most severely, most immigration research seems to test hypotheses that can already be expected prior to data collection to send a pro-immigration message. For instance, there is a huge literature on people’s biased immigration beliefs. This is usually measured as people misestimating immigration-related statistics. Researchers usually ask people about a specific immigration-related statistic and then compare these estimates to the true values (for a review article click here). But which out of the Millions of existing statistics should a researcher choose? Some statistics paint immigration surprisingly positively. For instance, (a) immigrants overall in the US are not more criminal than natives. Other statistics paint immigration very negatively. For example, (b) African or Middle Eastern immigrants in European countries are often 40 times or more likely to commit murder or rape than natives are. Since these numbers seem surprising to most of us, one can expect that survey participants will also think about immigration more negatively than statistic (a) suggests and more positively than statistic (b) indicates. To me, the choice researchers made in selecting which specific statistic to ask people about appears motivated to make people look like they view immigration negatively by only asking them about statistics where immigrants do surprisingly well. In particular, even though this may be the statistics people care the most about, there is basically no such research on beliefs about capital crime by asylum seekers, African, or Middle Eastern immigrants.

Moreover, why do we only study how ordinary people are supposedly too uninformed for us to take their anti-immigration attitudes seriously and attribute them to fake news rather than serious preferences? How about biases of policymakers or researchers themselves? These groups come primarily from more well-off backgrounds and have only contact with a very select group of elite migrants. They are rarely confronted with the many low-educated, non-integrated immigrants and the problem these immigrants cause. A plausible conjecture is therefore that researchers and other elites underestimate the problems immigrants cause for ordinary people. This hypothesis is, in the modern cultural sense, as right-wing as the idea that ordinary people are biased is left-wing. There is a lot of research on the latter, but basically nothing on the former. Importantly, both may be true. It’s just that we only hear all day about a selected share of hypotheses because only they are being tested.

Even more generally, there seems to be more research that focuses on improving the lives of immigrants rather than natives. The dependent variable in many studies is some measure of how well immigrants are off. The study then finds that some form of investment is good for immigrants and concludes that policy should make these investments. But what about natives? Investments that are purely chosen to benefit immigrants are not necessarily in the natives’ interest; they can even be harmful to them. But this possibility is often not even considered. For instance, the asylum system is great for immigrants since it enables them to come to any country and receive social benefits without any qualifications. But because such a system attracts lazy and exploitative people, the asylum system is probably bad for natives. In my experience, researchers are much more likely to ask how the asylum system impacts the well-being of immigrants than the welfare of natives.

It’s not only immigrationAll of these results are unlikely to be unique to immigration. Surveys consistently document strong leftward skew among academics, especially in social sciences and humanities. For instance, Langbert (2018) studies the political registration of professors in top-tier liberal arts colleges. He finds that 39% of the colleges in his sample have no Republican professors at all. The political registration in most of the remaining 61% is also strongly skewed, with over 90% of professors being Democrats. Van de Werfhorst (2020) obtains similar results for Europe and notes a particularly strong bias and lack of opinion diversity regarding immigration attitudes.

Relatedly, an interesting working paper by Goldstein and Kolerman (2025) tracks the attitudes of U.S. students over time. They find that, relative to natural sciences, studying social sciences and humanities makes students more left-wing, whereas studying economics and business makes them more right-leaning. The rightward effects of economics and business are driven by positions on economic issues, whereas the leftward effects of the humanities and social sciences are driven by cultural ones. Interestingly, this simultaneous economic right-wing and cultural left-wing bias is also found regarding politicians and journalists. Goldstein and Kolerman find that their effects work through academic content and teaching rather than socialization or earnings expectations. A potential explanation is that culturally left-wing and economically right-wing professors, respectively, who make up the vast majority in universities, only tell their students studies that support narratives with which they are ideologically aligned.

Implications and personal opinionIt is not necessarily problematic if researchers are more liberal than the general public, but it is problematic if these attitudes make them analyse data in a biased way, to arrive at conclusions that reinforce their prior attitudes. In that case, immigration research ceases to be research and transitions into propaganda, where only hypotheses are tested that one can anticipate to portray immigration positively, and the research design is chosen to obtain the desired conclusion.

In recent years, normal people have gotten more sceptical regarding scientists in general, particularly vivid examples include Covid 19 and climate change. As a scientist myself, I understand this development and do not think of it as irrational. The evidence presented here makes a good case that scientists produce systematically and strongly biased output. My sense is that many people are well-aware of this bias from the way they see scientists use framing to vilify valid arguments, fail to address obvious concerns, or employ double standards. Hence, people know that it is not optimal for them to take what scientists say at face value. Instead, they must factor out the scientist’s bias. Because this is very difficult and costly to do, it can be optimal to just completely disregard everything scientists say and instead rely on personal experience or discussions with friends.

The tragedy is that this behaviour is caused by only a few activist sub-disciplines that have essentially turned into left-wing propaganda machines. It is quite clear that the human-made climate is real and that Covid 19 was a serious threat to our healthcare system. In general, hard sciences are much more reliable than social sciences because standards are higher and topics are less emotional. In that sense, the example and evidence provided here are a most likely case for researcher biases. But they occur on the political topic most important to Western citizens, and on this basis, decisions are made and justified that majorities disagree with. Hence, these biases have a huge impact on distrust toward science and elites in general.

This distrust now has political implications that hurt academia in general. The fact that researchers are much more liberal than ordinary people is consistent with the populist narrative, according to which the elite, comprising politicians, scientists, journalists, and so on, are all much more culturally liberal than voters and citizens in general. Regarding politicians this is also correct, and there is also corresponding evidence regarding journalists. The biases of these groups have the potential to compound: researchers bias their findings toward the left, which are then picked up by journalists who frame the studies even more left-wing than they already are. Politicians then pick the most left-wing interpretation of what journalists provide to arrive at even more extreme policies.

The resulting, unpopular policies now backfire as right-wing populists fill the resulting representation gaps to win elections. Once in power, populists often defund universities, especially departments in the social sciences. To me, it is not clear how this move can come as a surprise. Given how unpopular social scientists have become as a result of their activism, such policies are likely popular.

My message to researchers is thus: improving your research validity, which includes screening out those who exploit our research environment to fabricate (left-wing) propaganda. You may be attacked for many reasons, but those who attack you can only get away with it as long as you are unpopular with the public. You are unpopular with the public due to the actions of a minority of activist social scientists who prioritize left-wing propaganda over the search for truth. It is in our best interest to correct this sorry state of affairs, and we can do so ourselves.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.