How To Get Zero Inflation For Three Centuries

In addition to his long-standing feud with the Federal Reserve over interest rates, President Trump styles himself as something of an expert on monetary policy. He said this on November 7:

We have almost no inflation. We are down now to 2%. And we will be at, maybe 1%. You want to always stay above 1%; you want a little tiny bit of inflation. We are at a perfect number.

A lot of people have the same idea about “inflation” Trump has, which is that “a little tiny bit” of it is a good thing, but nobody ever explains why that should be so. And a lot of people would also agree with the president that a two percent inflation target is a pretty decent achievement in setting monetary policy, if you could do it.

Our ancestors did better than that. We could do the same, but we have forgotten how to do it.

Now “inflation” can be defined in several ways, but ultimately, it’s a degradation of the currency unit. All currencies in the world today are so-called “fiat” currencies; that is, they are not defined in terms of an objective benchmark such as a fixed quantity of gold. The U.S. dollar is the most successful of the fiats, but it, along with the others, is chronically losing value.

Inflation is not the same thing as “higher prices.” Certainly, higher prices are a consequence of inflation, not its cause. To find the cause, measure a currency’s performance against gold. If the “price of gold” rises to $5,000/ounce from its present level of about $4,000/ounce, that movement is understood as the U.S. dollar depreciating in value rather than gold appreciating in value.

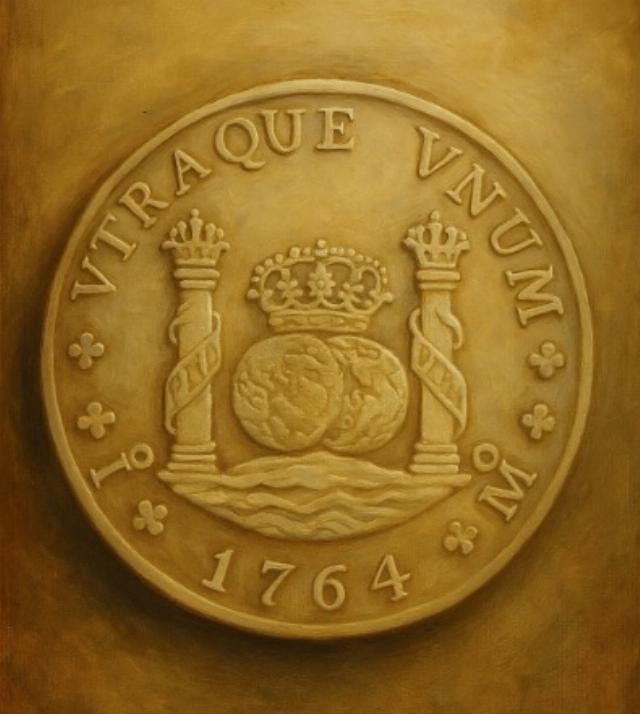

In the past, silver played a monetary role side-by-side with gold. The Spanish “piece of eight,” or real de a ocho, was a silver coin that could be physically cut into eight pieces for smaller transactions.

Spanish pieces of eight circulated in the American colonies and continued to do so for decades after the United States gained its independence. They were finally pulled from circulation with the Coinage Act of 1857, which banned the use of foreign coins as legal tender. Still, the U.S. dollar owes much to its Spanish heritage. Indeed, one of the best explanations for the dollar symbol (an “S” that has a line through it), is that it refers to the Spanish Habsburg emblem, which shows two pillars (the Gates of Hercules), with the words “Plus Ultra” woven through them.

Image created using AI.

Then there was the American convention of dividing the dollar into eight bits, and until 2001, Wall Street quoted stock prices in eighths of a dollar.

In its day, which lasted three centuries, the Spanish piece of eight played the same role in international trade that the U.S. dollar plays today. It was the world’s most used medium of exchange. But unlike today’s dollar, its performance in terms of retaining its value was, well, sterling.

We can make that claim by putting the Spanish piece of eight through a present value/future value analysis. It’s really not that much of a nerdy thing to do, and AI can help us with the math.

For the present value, let us take the amount of silver in a Spanish piece of eight at its first minting, and for the future value, let us take the amount of silver in the same coin in 1857, the year when all foreign coins were made illegal in the United States.

The piece of eight was first minted in 1537 in Mexico City, some 16 years after the conquistadors conquered the place. It contained 394.5 grains of silver.

After Mexico got its independence from Spain in 1821, it continued minting pieces of eight, but by 1857, the silver content had dropped to 377 grains.

Notice that between the two dates, the quantity of silver decreased, while the coin’s face value, equal to eight reals, remained the same. Let us take the difference as the degradation of the currency unit. By 1857, it would have taken more pieces of eight to buy a fixed quantity of silver than previously.

We now have all the information we need to calculate inflation.

The formula for the future value is:

FV = PV(1 + r)^n

Where:

• FV = Future Value (377 grains)

• PV = Present Value (394.5 grains)

• n = elapsed time, or 320 years

• r = annual rate of change

Solve for “r.” Our AI app tells us that the annual rate of decline of the silver content in a Spanish piece of eight was -0.0144% per year.

This degradation of the currency—or “inflation”—was less than two one-hundredths of a percent per year for 320 years!

Fast forward to the 21st century, where really smart policy wonks know exactly how to fine-tune monetary policy and where they think that, if they achieve a two percent inflation target, they should be praised.

Today, the price of gold is poised to continue its march north. Gold is signaling Danger: Higher Prices Ahead. It is saying something other than Trump’s claim that inflation is tame and at “a perfect number.”

There is no reason why any currency in the world should settle for even a slow pace of eroded value. Our ancestors knew how to stabilize the value of money. We have forgotten.

Image created using AI.

JAMES SORIANO is a retired Foreign Service Officer. He has previously written on The American Thinker on the gold standard and on the Ukraine War.