"Legally Clean" Water: How Modern Water Treatment Actually Works

Aurmina End-of-Year SaleAs we close out Aurmina’s first year, really, its first few months, we wanted to mark the moment with something simple: gratitude.

Lisa, Scott, and I built Aurmina because we believed there was a missing piece in modern water treatment, and we’ve been genuinely moved by how many people immediately understood what we were trying to do. Watching this small company help real people has been deeply satisfying, and we wanted to say thank you.

Through the end of the year, we’re offering 25% off single bottles, with no limit on quantity. For those who already know they’ll be using Aurmina long-term, the 6-pack remains the best value at 34% off, so don’t outsmart yourself by buying six singles.

Discount Code: HOLIDAY

If you’ve been following my water series, you already know why this exists. Aurmina isn’t about stripping water down to nothing. It’s about restoring order, clarity, and purity after modern treatment has done its job.

And in the spirit of transparency (and a little humor), the first draft of the post below was written before Aurmina even existed. If that makes this post a marketing scheme, it’s the most accidental one I’ve ever been part of.

Either way, this is our thank-you. The sale runs through the end of the year.

This post originally focused on just one half of our environmental water cycle, i.e. the journey of your drinking water from a surface or groundwater source to the water treatment plant and then to your home. Only later did it occur to me that I was ignoring the other half, how the water that comes out of your home, office building, school, or factory goes back to the environment.

Neither part is pretty, but the wastewater part of the cycle is obviously more challenging to contemplate.

Let’s get through this quick, because I think we all agree that we are way more concerned with the water that comes into our home for drinking and cooking than we are with what happens after it leaves (although it is disingenuous to ignore that half because, as you will learn below, the two are, and have to be, directly connected).

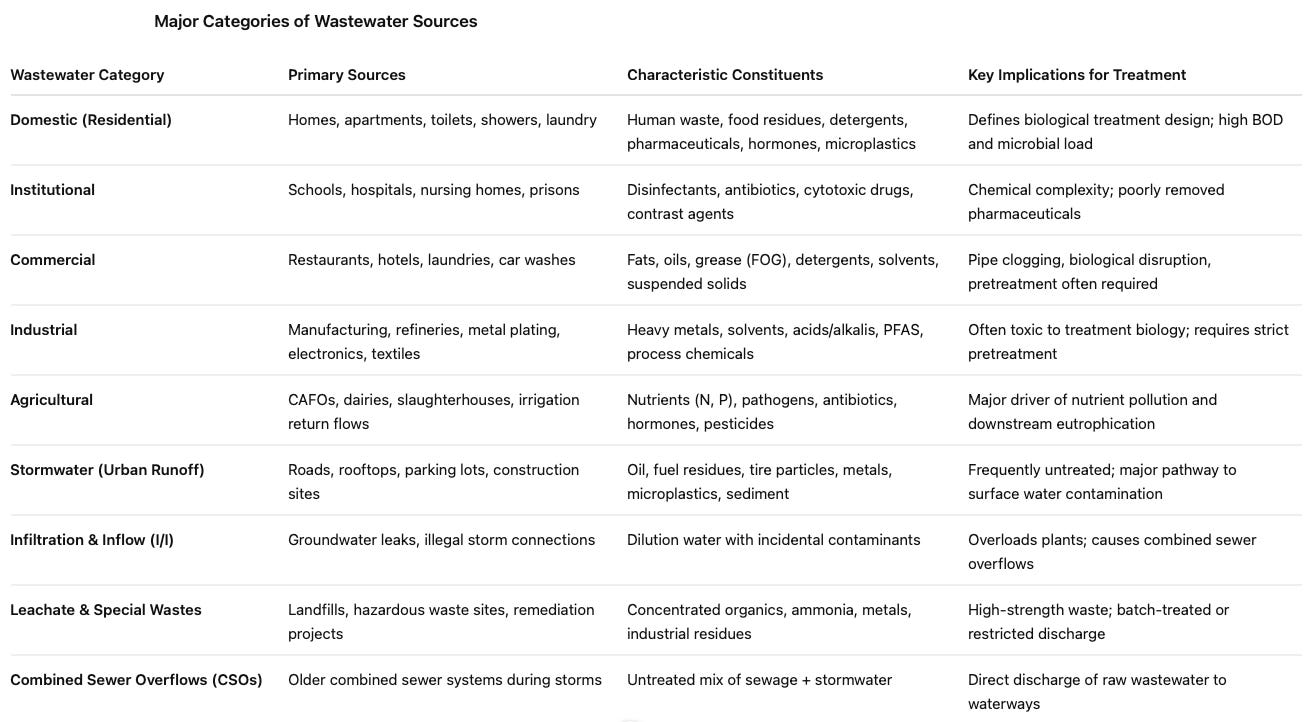

For brevity, I took all I had written and had AI build me a table. The most uncomfortable to read is the “constituents” column:

Now, in terms of understanding the differences between drinking and wastewater treatment plants, lets start at a high level; one prepares water for ingestion into the body, the other prepares water for discharge into the environment.

In other words, drinking water treatment takes raw water from a natural source and make it safe, stable, and distributable as drinking water. Their core treatment philosophy is to control what is visible, filterable, and immediately dangerous, then chemically stabilize the water so it behaves predictably in infrastructure. Water that leaves a drinking-water plant is considered successful if it is clear, noninfectious, chemically compliant, and pipe-safe. In essence, they try to prevent immediate harm and protect infrastructure.

Wastewater treatment plants take sewage and industrial effluent and make it environmentally acceptable for release back into rivers, lakes, or the ocean. Their core treatment philosophy is to use biology itself to break down organic matter, then remove or neutralize what remains. Treated wastewater is considered successful if it does not damage downstream ecosystems. They do not focus on making it drinkable. Not so fun fact: In many places, treated wastewater is intentionally returned to the same waters that supply drinking water.

Ultimately, drinking water treatment manages chemistry, while wastewater treatment processes biology

That inversion explains why modern drinking water, although legally “safe” is biologically thin, while treated wastewater is often released in a state that supports microbial and aquatic life more readily than the water we drink.

Now, although the below study found that Themarox (the mother solution of Aurmina) could successfully treat Mexico City wastewater, I’m a drinking water guy now, not a wastewater guy, so let’s move on with the original focus of this post.

Contemporary water treatment is designed to meet regulatory thresholds by stabilizing chemistry and suppressing visibility, not by restoring biological or mineral integrity.

Modern municipal water treatment is often assumed to be a process that “cleans” water in a comprehensive sense. In practice, it is a system designed to make water compliant with regulatory standards and safe from acute infectious disease, not to restore water to a biologically intact or mineral-complete state.

The primary goals of conventional drinking-water treatment are to remove visible particulates, reduce microbial pathogens, and ensure that finished water meets maximum contaminant levels established by regulation.

These goals emerged historically in response to cholera, typhoid, and other waterborne epidemics, and they remain the foundation of treatment design today.

Treatment trains are therefore built to “manage turbidity” (water treatment language for keeping the water clear looking), disinfect against bacteria and viruses, and stabilize water chemistry so that it can be distributed safely through pipes without excessive corrosion or scale formation.

Thus, modern drinking water systems are engineered to meet concentration-based regulatory thresholds, not to resolve the total chemical burden that modern water now carries.

Modern water treatment is literally designed to keep water’s content invisible, dissolved, dispersed, and diluted below perception. It is almost like saying, “let’s employ methods so that they can’t see what is in their water.” If you think I am being alarmist or don’t understand water treatment, unfortunately you would be wrong.

If you think that delivering water of the highest purity possible is the main goal of municipal water treatment, that would be as ridiculous as thinking the pharmaceutical industry’s main goal is to keep you healthy (sorry not sorry).

Here I will argue that their main goals are twofold: keep the water clear, and keep it from messing up the pipes (Ok, fine, they also want it free of microbes too).

One of the least appreciated aspects of modern water treatment is that many contaminants are not removed and are instead managed chemically. pH adjustment, corrosion inhibitors, and blending are routinely used to keep contaminants in solution or prevent them from leaching from pipes.

If you think that sounds bad, let’s look into “how the sausage gets made” so to speak; meaning the methods they employ to get your water to arrive looking clear (and it’s not from piping it from a pristine mountain spring).

Compliance with regulatory and clarity standards entails:

keeping foreign substances from having to be removed or from aggregating by keeping them dissolved, dispersed, and chemically stable below action limits

intentionally conditioning water with sequestrants (polyphosphates), corrosion inhibitors, and disinfectants that favor solubility and suppress precipitation to prevent scaling, corrosion, turbidity, and distribution failures

avoiding even trying to eliminate the low-level dissolved metals, small organics, chelated compounds, and persistent industrial residues by overly focusing on removing particles and pathogens

OK, let’s go back to the water treatment industry, and it’s main goal, which is to remove largely physically discrete, filterable matter like;

Suspended solids (sand, silt, rust, clay)

Colloidal matter large enough to scatter light (turbidity-causing material)

Biological particulates (bacteria, protozoa, algae)

Flocculated aggregates formed during treatment

Corrosion debris (pipe scale fragments, iron oxide particles)

Problem: they don’t focus on removing the dissolved and/or chemically complexed substances.

They don’t do this because, once water enters the distribution system, any tendency for material to settle or drop out is treated as a failure mode, further reinforcing chemical stabilization over resolution.

Conventional municipal water plants typically remove 85% or more of solids, most pathogens, some heavy metals, nitrates, and disinfect most bacteria. Advanced treatments, such as carbon filtration, ozonation, reverse osmosis, or advanced oxidation, can reduce certain “contaminants of emerging concern” (CECs) and micropollutants (like pharmaceuticals, PFAS, and some pesticides).

Still, removal rates vary from <50% to ~99%. Thus, removal rates vary widely, depending on the substance and plant technology.

Many toxins, including endocrine disruptors, pharmaceuticals, antimicrobial-resistant bacteria, microplastics, and some industrial chemicals, are only partially removed or pass through most plants.

Despite water safety laws, thousands of chemicals found in the water supply are not routinely monitored or regulated. These include:

Pharmaceuticals (antibiotics, hormones, antidepressants)

Endocrine disruptors (phthalates, bisphenol A)

Industrial byproducts (PCBs, volatile organics)

Microplastics and nanoplastics

PFAS and related fluorinated compounds (many remain unregulated)

Newly identified “contaminants of emerging concern” (e.g., flame retardants, illicit drugs, new pesticides)

Natural toxins (algal toxins, mycotoxins)

Resistant pathogens and genetic material (viruses, antimicrobial gene fragments)

Uncharacterized Organic/Chemical Pollutants from Agriculture/Fracking/Mining

Disinfection byproducts (THMs, HAAs) — currently discussed elsewhere

Cyanotoxins (microcystins) — partially covered under algal toxins

Transformation products (chlorinated pesticide metabolites)

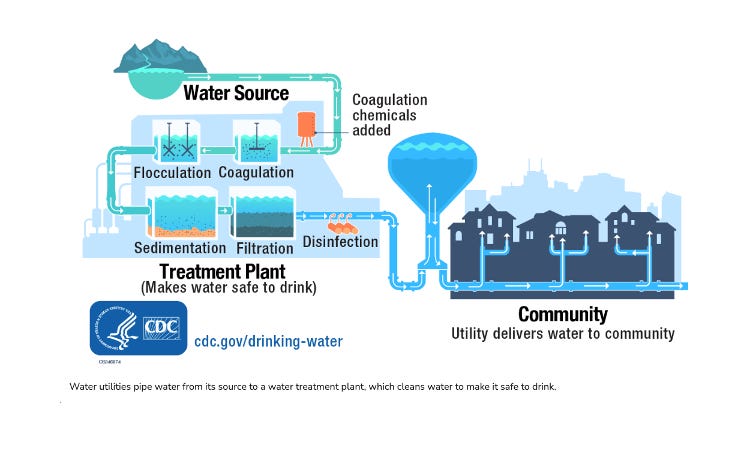

For surface water systems, treatment typically begins with coagulation and flocculation. Chemical coagulants such as aluminum sulfate or ferric salts are added to destabilize suspended particles, allowing them to aggregate into larger flocs. These flocs settle out in sedimentation basins or are removed by filtration.

Filtration commonly uses sand, anthracite, or granular media to remove remaining particulates. The final and most critical step is disinfection, usually accomplished with chlorine, chloramine, ozone, or ultraviolet light.

Note: My other book being published right now is The War on Chlorine Dioxide, the main focus of which is on the decades long war suppressing the knowledge of, use of, and research into its efficacy as an orally ingested therapeutic.

One of the main arguments supporting its safety is that many have been ingesting chlorine dioxide in our drinking water for over 75 years. Note that, although it has chlorine in its name, no free chlorine is liberated when used, thus it is not a chlorinating agent.

However, in the United States, chlorine dioxide is used only in a minority of water systems, whereas in parts of Europe it is used far more commonly as a primary disinfectant or an oxidant in municipal water treatment.

Now, the reason why it is not used in the U.S is particularly revealing about our water treatment industry. Chlorine dioxide was not displaced here because it posed a uniquely unacceptable risk, but because, in case of a screw up with it, its risks would be immediate, quantifiable, and resistant to regulatory dilution.

“Resistant to regulatory dilution.” What the hell does that mean? I looked it up: it is when a hazard is made administratively tolerable by employing a few tricks like averaging exposure over time, spreading risk across large populations, and redefining “acceptable limits.”

Thus, “we” prefer to use compounds which rest on long-term rather than immediate harm, because when levels are accidentally exceeded, the harms are buried long term, and thus, “temporary exceedance” does not force immediate action.

You see, the principal byproducts of chlorine dioxide (chlorite and chlorate), if in excess, could produce acute, oxidative injury to red blood cells in a subset of people like infants, individuals with G6PD deficiency, and dialysis patients. A chlorine dioxide miscalculation shows up fast, affects vulnerable populations first, and creates immediate legal and regulatory exposure.

That is the reason why most facilities prefer chlorine. Although it too produces toxic byproducts (trihalomethanes), those are associated with long-term risks (cancer). When limits are exceeded, they rarely require immediate shutdowns. A small increase in lifetime cancer risk is considered administratively preferable to the risk of acute microbial outbreaks, so they can risk “exceeding” more easily than with CLO2.

Oddly, that is not the case in Europe where they encourages alternatives to the use of free chlorine when possible. The practical outcome is a regulatory system that disfavors disinfectants whose harms are prompt and visible, while accommodating those whose harms emerge slowly, disperse across populations, and remain statistically manageable.

This reflects a preference for risks that are administratively easier to absorb than it reflects relative toxicity. What a world.

Groundwater systems are often treated less aggressively than surface water because groundwater is assumed to be naturally filtered. In many cases, groundwater treatment consists primarily of disinfection and, where necessary, iron or manganese removal.

This assumption of inherent cleanliness overlooks the fact that groundwater chemistry can be profoundly altered by pumping, redox changes, and long-term exposure to agricultural, industrial, and urban contaminants. Treatment addresses compliance, not restoration.

Orthophosphate is commonly added to municipal water supplies to coat pipes and reduce lead and copper release. This does not remove metals from the system; it alters their chemical behavior to reduce immediate exposure.

Similarly, contaminants present below regulatory thresholds are rarely addressed at all. Treatment systems are not designed to remove dozens of trace organic compounds, pharmaceuticals, or endocrine disruptors unless specifically required to do so.

Disinfection itself creates new chemicals. When chlorine or chloramine reacts with organic matter in water, it forms disinfection byproducts such as trihalomethanes and haloacetic acids. These compounds are regulated, but only within limits considered acceptable based on population-level risk models.

Treatment plants adjust chemistry to balance microbial safety against byproduct formation. This balancing act reflects regulatory optimization, not biological ideality.

Standard treatment does not restore mineral balance, trace element diversity, or natural redox structure. Calcium, magnesium, bicarbonate, sulfate, and trace minerals are not replenished unless required for corrosion control or aesthetic reasons.

Reverse osmosis, ion exchange, and advanced membrane technologies can remove a wide range of contaminants, but they also remove minerals indiscriminately. When used at scale, they require post-treatment stabilization to prevent aggressive, corrosive water from damaging infrastructure.

Ultimately, modern water treatment defines success as regulatory compliance. If water meets maximum contaminant levels, maintains disinfectant residuals, and flows safely through pipes, it is considered treated.

The system is not designed to ask whether water is biologically coherent, mineral-complete, or physiologically supportive. Those questions fall outside the regulatory framework.

What emerges from this framework is a system optimized to control what is visible, measurable, and enforceable. Acute toxicity is addressed. Chronic, low-level, multi-chemical exposure is normalized. Mineral depletion is unmeasured.

Water leaves the treatment plant stable, disinfected, and “legally clean,” yet often chemically oversimplified and biologically incomplete.

All the above leaves a practical question for anyone paying attention: what do you do about the water you actually drink (note that I love asking a question which allows me to literally “sell” you the answer).

Aurmina was developed for the part of the problem modern treatment never attempts to solve. It operates downstream, at the point where water meets biology. It is a “last line of defense” against the byproducts of human and industrial activity that our modern water supply carries.

Aurmina removes disordered mineral load, collapses colloids, binds reactive contaminants, and restores mineral coordination and redox balance in the remaining water.

The result is water that behaves differently: less aggressive, more electrically coherent, and more physiologically compatible, without first stripping it through reverse osmosis or distillation, or forcing it to be hardened or softened, and then attempting to bolt life back onto it afterward.

Aurmina does not ask you to change how your city treats water or how your house is plumbed. It optimizes the water you ingest.

If you value the late nights and deep dives into all the “rabbit holes” I then write about (or the Op-Eds and lectures I try to get out to the public), supporting my work is greatly appreciated.

If you want to learn more about the water purifier we made from Shimanishi’s volcanic-mineral complex, go to Aurmina.com where we are running a 25% off end-of year sale.

Yup — not one, but two books are dropping from yours truly (at the same time? What?)

If, instead of (or in addition to) these Substack posted chapters, you prefer the feel of a real book, or the smell of paper, or like to give holiday gifts, pre-order From Volcanoes to Vitality, my grand mineral saga, shipping end of January.

And if you want to read (or gift) another chronicle of suppression, science, and survival, grab The War on Chlorine Dioxide—the sequel you didn’t see coming—shipping early to mid-January. On this one, I say: “Buy it before they ban it.” Hah!