The reckoning on immigration is here

The easy part is over.

Americans wanted the borders closed.

For decades, the legacy media and politicians in both parties ignored that wish, claiming the United States had to accept and support an endless flood of illegal migrants. The disconnect between average people and elite opinion was so obvious that academics wrote papers about it.

President Trump broke with the elite consensus from the first day of his 2016 presidential campaign, when he announced “I will build a great, great wall on our southern border.” No issue proved more politically potent for him.

In his second term, Trump has kept his promise. The wall may not be literally complete, but it might as well be. Customs and Border Patrol reports monthly “encounters” with illegal migrants on the southern border have fallen about 95 percent from the Biden Administration average, and 97 percent from their 2023 peak.

—

(Close encounters of the truthful kind. For pennies a day.)

—

But closing the border to new arrivals does not undo the fact that tens of millions of people are living in the United States illegally, or with quasi-legal “asylum” or “temporary protected” status the Trump Administration is now seeking to revoke.

Just how many people are inside the United States illegally? We do not really know. In 2024, the Department of Homeland Security put the figure at roughly 11 million in 2022 — and said the number had not changed for almost 20 years.

That estimate is nonsensical, given that close to 10 million people arrived in the first three years of the Biden Administration alone.

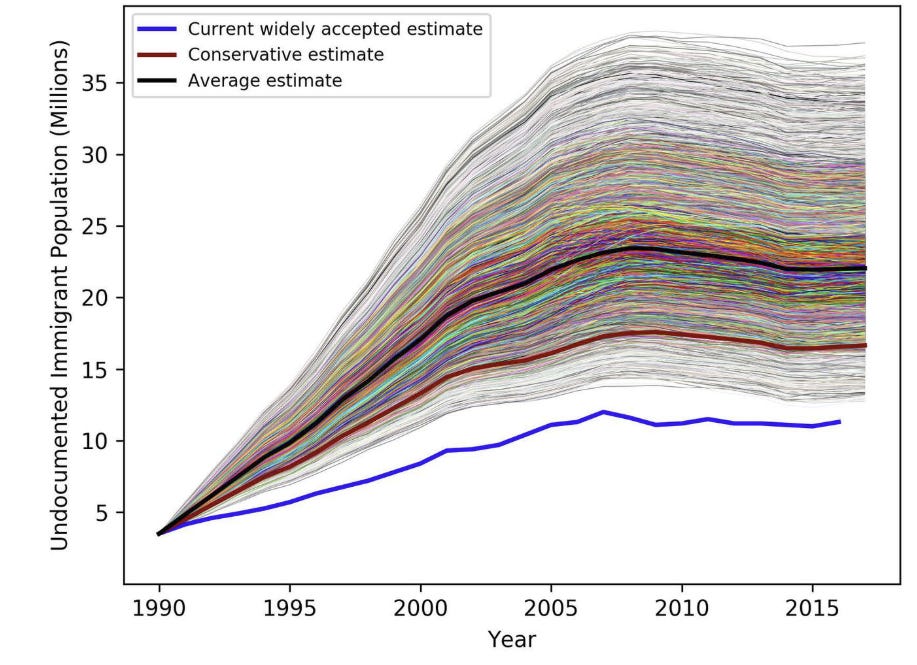

In 2018, in a paper that should have received more attention than it did, three researchers from Yale and MIT estimated about 22 million people — double the official figure — were living illegally in the United States.

As the paper explained, the consensus 11 million figure comes from a census question that “requires accurate responses from survey respondents when asked where they were born, and whether they are American citizens.” In other words, the survey required illegal immigrants to tell on themselves — to government officials. (It’s a surprise the figure was not zero.)

The researchers used a different method, netting out changes in immigration over time by estimating the number of migrants entering, leaving, and dying. To be clear, this was an exercise in modeling, with all the uncertainty that implies. But even a modeled figure is better than a clearly nonsensical one.

Their best estimate was that the number of illegal migrants rose from under 5 million in 1990 to about 22 million before the 2008 financial crisis, then stayed roughly flat for the next decade. This growth makes intuitive sense. The American economy was very strong in the 1990s, and making money is the primary reason people uproot their lives and cross borders.

—

(The 2018 Yale estimate of illegal immigrants in the United States. Note the black line hovering just over 20 million.)

—

The prolonged recession and slow recovery from the 2008 financial crisis kept a lid on illegal migration for the next several years.

Then three factors combined to drive up migration.

Economic growth accelerated in President Trump’s first term.

Leaders in the Democratic Party began to speak out aggressively against any enforcement of border laws.

And migrants realized they could use asylum claims to gain entry into the United States and become quickly eligible for Medicaid and other public benefits programs, which previously had not been available to them. The number of people claiming asylum rose from 44,000 in 2011 to 209,000 in 2017, according to a State Department report to Congress.

When the Biden Administration took over in 2021, these trends exploded.

Covid lockdowns and plunging tourism devastated Latin American economies, making the United States more attractive. The official 2020 Democratic Party platform essentially called for an end to border enforcement. And requests for asylum surged even further, with almost 480,000 people asking for asylum in 2023 — even as the Biden Administration created other new pathways to admission, like the “Humanitarian Parole Program.”

—

Millions more people simply came across the border without even the fig leaf of an asylum request or humanitarian parole. In 2024, the Congressional Budget Office estimated that about 65 percent of all the migrants in the post-2020 surge — roughly five to six million people — fell in that category.

At an minimum, the United States now probably has close to 20 million people inside its borders who have no legal right to be here under any circumstance. The number may well be closer to 30 million, especially as the Trump Administration strips away the Biden Administration’s expansion of asylum and “humanitarian parole.”

Many of those people are hardworking migrants whose only crime is their immigration status. Others have depended on public assistance since the day they arrived on American soil and have no plans to or realistic hope of getting off it. And some — a small but still real percentage — are criminals.

—

(Unreported Truths: so good it’s almost criminal. For pennies a day.)

—

But they are all present illegally and thus face the risk of deportation. Until now, that risk had been largely theoretical. The United States had operated under a fragile don’t-ask-don’t-tell-style consensus on deportation, which was more or less as follows:

If you can get across the border and you work and do not commit crimes, you will not face a serious risk of immigration enforcement or deportation. And if you have children here, they will be American citizens, under birthright citizenship.

To be clear, the left — not the right — destabilized this bargain.

Opening taxpayer-financed programs to millions of asylees, refugees, and other immigrants with quasi-legal status infuriated many native-born Americans. In combination with the sheer number of new arrivals, the welfare expansion understandably led to an angry backlash.

Now the Trump Administration has made clear that in its view closing the border was the first step, not the last, in immigration enforcement, and that the United States should view the presence of tens of millions of illegal migrants as a mass violation of its laws and sovereignty, even if they are committing no other crimes.

We are about to find out whether most Americans agree.

The easy part — closing the borders — is over.

The hard part — deciding what to do about the people who are already here — comes now.