The ever-expanding modern vaccination era may be ending at last

(PART 1 of 2)

In the beginning was the smallpox vaccine.

In the late 1700s, an English physician named Edward Jenner realized milkmaids infected with cowpox rarely fell prey to smallpox, a devastating virus. Jenner began deliberately giving people cowpox and found they too became immune to smallpox.

Over the next two centuries, humanity beat back bacterial and viral diseases. The British epidemiologist John Snow realized cholera was spread by sewage. The German scientist Robert Koch and French physician Louis Pasteur invented germ theory. The British bacteriologist Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin. The American physician D.A. Henderson finished Jenner’s work with a global effort to eradicate smallpox.

It is vital not to understate the role vaccines played in this victory over disease, suffering, and death. But it’s vital not to overstate it, too.

—

(Not understating. Not overstating. Just the truth.)

—

The greatest gains against infectious disease came before most modern vaccines were developed. They came from simple and relatively inexpensive improvements in nutrition and public sanitation.

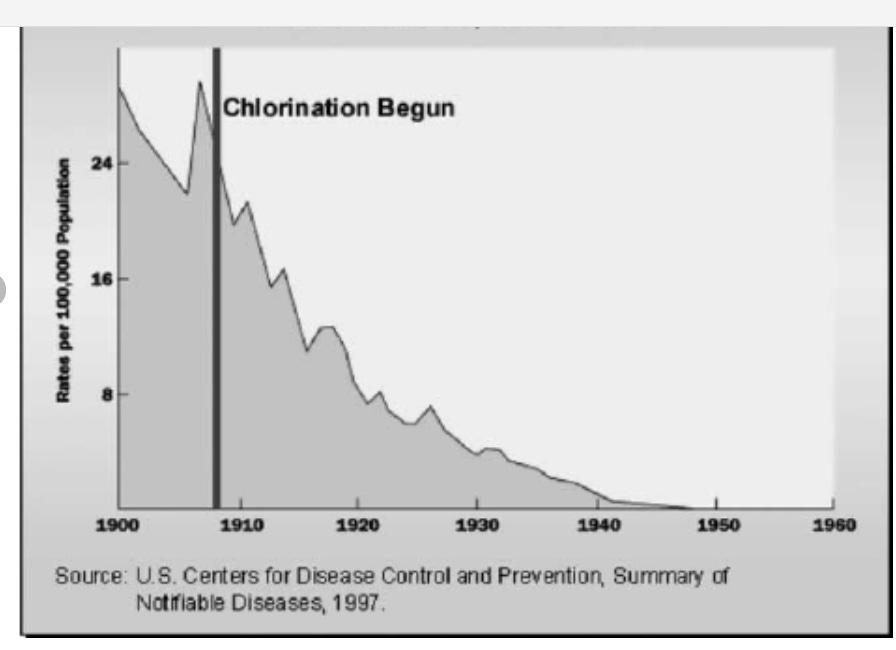

For example, check out American deaths from typhoid fever, a nasty bacterial illness that killed about one-third of the Civil War soldiers it infected, in the first half of the 20th century:

—

A great success for vaccination? Nope.

The typhoid vaccine is only marginally effective and not even recommended for Americans. As the chart above shows, the great innovation in defeating typhoid came when municipal water systems began adding chlorine to treatment plants. Chlorine kills typhoid, cholera, and other waterborne bacteria and viruses cheaply and effectively.

Of course, not every infectious disease is waterborne. Viruses and bacteria have evolved to use every conceivable method of transmission, from air to blood to touch to intermediate hosts like mosquitoes.

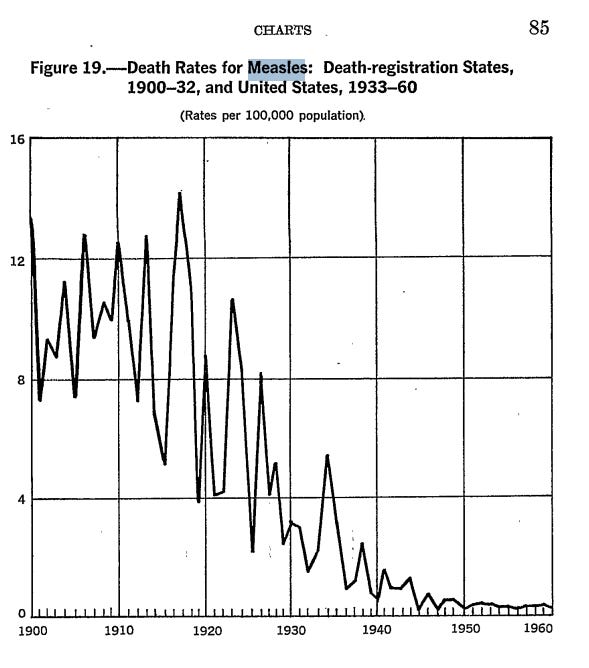

Still, whatever the mechanism of transmission, nearly all infectious diseases have followed the trend of typhoid. For example, deaths from measles in the United States plunged decades before the measles vaccine was introduced in 1963, as the Centers for Disease Control itself noted in 1968:

—

(Please note this chart ends BEFORE 1963. In other words, the entire mortality decrease occurred before any measles vaccine existed.)

—

The reason is simple.

Along with improvements in sanitation, we have had massive improvements in nutrition in the last century. People are healthier and have much better access to vitamin- and calorie-rich food. Americans in particular have such easy access to high-calorie diets that our biggest problem now is obesity. Famine essentially does not exist.

The care and treatment of sick people has progressed too, thanks to antibiotics and antivirals. The most notable advance of all on this front is the most recent. When the human immunodeficiency virus arrived around 1980, it was among the most deadly antigens humans had ever seen, killing nearly everyone it infected.

But bench scientists, physicians, and drug companies attacked it. And they won, devising a successful antiviral regimen in less than two decades. They did so with medicines, not a vaccine. HIV has proven remarkably resistant to vaccines.

—

In other words, even if physicians did not have a single vaccine to give patients, infectious diseases would be far less deadly in the United States and other developed countries than they were a century ago. They would be less deadly in other countries too; lower birth rates and better farming techniques mean that in all but the poorest countries, kids have become notably healthier.

None of this means vaccines are poisons.

Or that they cause autism. Or that we shouldn’t vaccinate kids against measles or other infectious diseases that pose a small though real risk to them, particularly with old-style inactivated-virus vaccines.

The mechanisms of action of those vaccines are well understood, and they have been given to billions of children worldwide for decades, with a very low risk of dangerous side effects. (I know, many of you will argue point to the rise in autism in the United States in the last 30 years as a counterexample. But much if not most of that increase is likely due to the reclassification of mental retardation and other developmental delays as autism, and much of the rest may well come from advancing parental age.)

What it does mean is that the discussion on vaccines has somehow become fetishized.

Epidemiologists, public health bureaucrats, and the media have somehow grown accustomed to promoting vaccines as miracles, our only line of defense from the epidemics of the Middle Ages. In fact, at least in developed countries, they are the fourth and least important bulwark, behind sanitation, nutrition, and medical care.

—

(The world without vaccines! At least according to Dr. Peter Hotez. Who has a vaccine to sell you.)

—

The public health love for vaccines is understandable.

On the sanitation side, the work is done, at least in the United States. And sanitation is both cheap and dirty, outside and beneath medicine. Nobody makes movies about heroic garbage workers or sewage treatment engineers.

Then there’s nutrition. But again, the gains from avoiding famine have been made, and medicine has played little role in those. Encouraging people to lose weight and take better care of themselves is important, but it will do little to save people from infectious disease (Covid’s habit of taking down the morbidly obese notwithstanding). And it’s hard.

Vaccines are easy. A simple jab or two in the arm for everyone. No need to get on a treadmill or eat vegetables. Vaccines are a way for public health bureaucrats — whether or not they have MDs — to feel like they too are heroic, life-saving front-line physicians.

—

(A shot of the truth. With your help.)

—

And vaccines fit the left’s conception of itself, I’m from the government and I’m here to help. No accident that so many the first Covid vaccine sites were giant municipally run operations in convention halls.

Never underestimate the power of a good story: a story of cheap, effective, government-provided, readily available cures for deadly infectious diseases.

But in the last 39 years, drug companies, public health experts, and journalists have stretched the truth of that story beyond recognition. And they are angry that anyone, much less someone in a position to stand up to them, like Robert F. Kennedy Jr., is now calling out what they’ve done.

(END PART 1 of 2.)